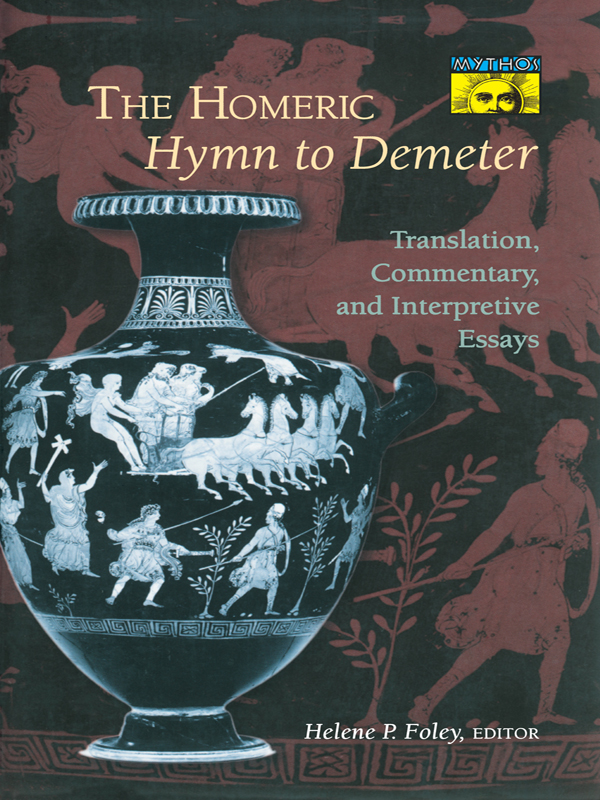

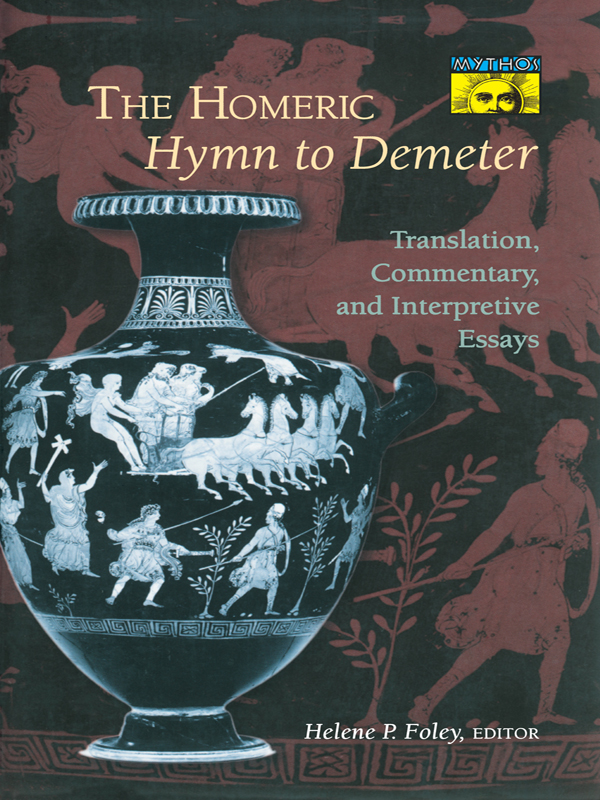

THE HOMERIC HYMN TO DEMETER

THE HOMERIC HYMN TO DEMETER

TRANSLATION, COMMENTARY, AND INTERPRETIVE ESSAYS

Edited by

Helene P. Foley

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

COPYRIGHT 1994 BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

POLITICS AND POMEGRANATES COPYRIGHT 1977 BY MARILYN A. KATZ PUBLISHED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 41 WILLIAM STREET, PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 08540

IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, CHICHESTER, WEST SUSSEX

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

THE HOMERIC HYMN TO DEMETER : TRANSLATION, COMMENTARY, AND INTERPRETIVE ESSAYS / HELENE P. FOLEY.

P. CM.

INCLUDES A TRANSLATION, THE GREEK TEXT, A LITERARY COMMENTARY, A DISCUSSION OF THE ELEUSINIAN MYSTERIES AND RELATED CULTS OF DEMETER, AN INTRODUCTORY ESSAY BY H. P. FOLEY, AND 5 PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED ARTICLES ON THE POEM AND RELATED ISSUES.

INCLUDES BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES AND INDEX.

ISBN 0-691-06843-7 ISBN 0-691-01479-5

1. HYMN TO DEMETER. 2. HYMNS, GREEK (CLASSICAL)TRANSLATIONS INTO ENGLISH. 3. HYMNS, GREEK (CLASSICAL)HISTORY AND CRITICISM. 4. DEMETER (GREEK MYTHOLOGY) IN LITERATURE. 5. ELEUSINIAN MYSTERIES IN LITERATURE. 6. DEMETER (GREEK MYTHOLOGY)POETRY. I. FOLEY, HELENE P., 1942 . II. HYMN TO DEMETER. ENGLISH & GREEK. 1993.

PA4023.H83H66 1993

883.01DC20 93-761

THIS BOOK HAS BEEN COMPOSED IN GALLIARD

THE PAPER USED IN THIS PUBLICATION MEETS THE MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS OF ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997)

(PERMANENCE OF PAPER)

THIRD PRINTING, WITH BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ADDENDUM, AND FIRST PRINTING IN THE MYTHOS SERIES, 1999

HTTP://PUP.PRINCETON.EDU

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

7 9 10 8

ISBN-13: 978-0-691-01479-1 (pbk.)

ISBN-10: 0-691-01479-5 (pbk.)

For Nicholas Foley

CONTENTS

MARY LOUISE LORD

NANCY FELSON-RUBIN AND HARRIET M. DEAL

JEAN RUDHARDT; TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY LAVINIA LORCH AND HELENE P. FOLEY

MARILYN ARTHUR, WITH A PREFACE BY THE AUTHOR WRITTEN TWENTY YEARS LATER

NANCY CHODOROW

ILLUSTRATIONS

After p. 75

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

O VER THE DECADE of the 1980s, the traditional Western canon has been subject to ardent defense and criticism. The privileging of the works of upper-class, Western, white males in standard introductory humanities courses across the United States has been at the center of this controversy. In many cases these courses have been adjusted to include a few token works by female, minority, or non-Western authors. Even this minimal gesture is more difficult in the case of Greco-Roman antiquity. Classical works often form a substantial part of the reading list of such courses, but few Greek and Roman authors were nonwhite or female. As a scholar and teacher of courses on women in antiquity, I often found myself consulted about what could be done. This book developed as part of an attempt to reconsider the syllabus of the typical core curriculum in response to the questions that have been raised about it. Western culture courses will continue to be taught (if not necessarily required) for many good reasons: above all to provide an understanding of the strengths and limits of the tradition. In reading Western literature critically, as anthropologists of the tradition, we must ask questions of the texts that the original authors might not have dreamed of asking. At the same time, when we introduce new texts into such courses, they should ideally continue to provoke dialogue of the same depth and complexity as well as to articulate in a provocative fashion with those already included.

Classical literature, far more explicitly than much later Western literature until the nineteenth century, virtually begs us to ask questions about gender. Plato and Aristotle confronted such issues directly. Most Greek comedies and tragedies commonly taught put gender conflict at the heart of the plot and allow their female characters to challenge male authority and assumptions: Aeschyluss Oresteia, Sophocles Antigone, Euripides Medea and Bacchae, Aristophanes Lysistrata, to name a few. As male-generated texts, these works reflect anxieties and concerns experienced by at least some Greek males about the nature of their society. What is largely missing, however, is a female perspective that could provide a glimpse of what ancient women meant to each other and the concerns that were of greatest significance to them. Although we have very little to go on in this respect, the fragments of the poet Sappho have of late been successfully taught in translation to a broad, general audience. In my view the text that can best supplement Sappho in putting the experience of ancient women and its symbolic importance into some perspective is the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, even though the anonymous author (or authors) of the poem was far more likely to have been male. (Sappho herself wrote hymns, but those who recited in the public contexts where the Hymn to Demeter was likely to have been performed would have been largely or perhaps exclusively men.)

As will be emphasized in my interpretive essay ( of this book), the Hymn puts the female experience of the goddesses Demeter and Persephone, as well as the disguised Demeters interactions with the mortal women of Eleusis, at the center of its narrative; it closes with the founding of the Eleusinian Mysteries, which accepted initiates of both sexes. The Demeter/Persephone myth was celebrated in all-female rites of Demeter. Because it was as participants in religious rites from marriages and funerals to festivals that ancient women engaged most directly and significantly in the public life of their culture, a poem that illuminates that experience can give us important insights into the lives of the Greek women of antiquity.

Nevertheless, there are many other reasons for giving this important poem a more central place than it has generally had in courses on Western culture and on classical antiquity. This book is in part an attempt to introduce general readers to the Hymn to Demeter, and to provide such readers with the background necessary to read the text in a knowledgeable and sophisticated fashion. In particular, I aim to show how the poem resonates with canonical texts like the Homeric epics, Greek drama, or the New Testament and how a knowledge of this text can correct a number of popular misapprehensions about ancient religion. Composed in the period between Homer and Hesiod and literature of the classical city-state, the Hymn offers a basis for discussing the transition between those two important periods and demonstrates the central role that ritual and cult (as opposed to myth) played in ancient religion; the poem also illustrates how the view of divinity offered in mystery cults differs from that represented in Homer and tragedy and permits us to examine a central religious mystery that is based on female experience and especially on the relation of mother to daughter. In addition, a knowledge of ancient mystery cults makes the transition to Christianity easier to locate historically and to understand.

By treating the Hymn to Demeter separately from the other Homeric hymns, I want to present the poem as a profound short epic, an outstanding representative of an often underrated literary form, and a brilliant work of literature in its own right. The earliest writers of Greek epic attributed an equal amount of prestige to hymnic poetry, the celebration of the deeds of the gods, and to heroic epic. As Hesiod put it in his famous cosmological poem the

Next page