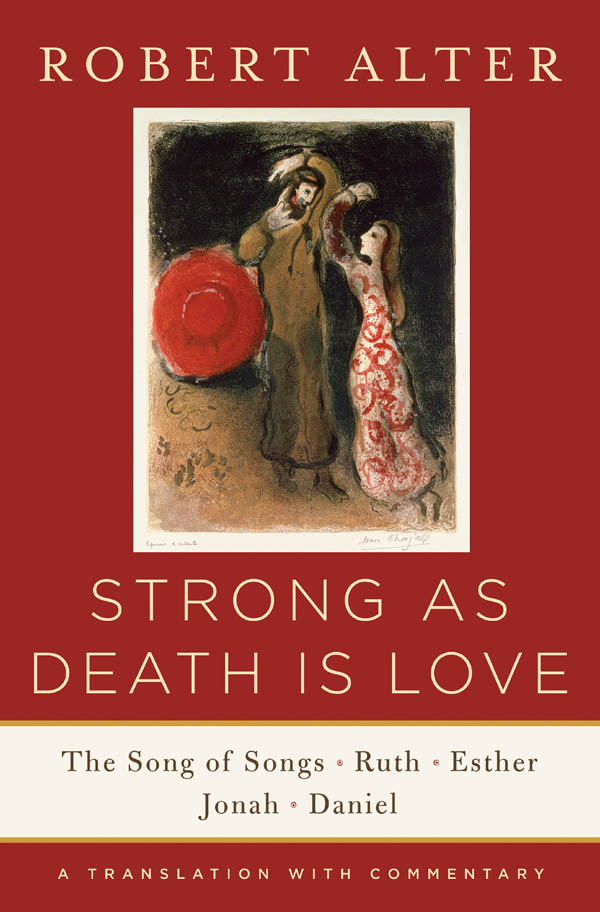

STRONG

AS DEATH

IS LOVE

THE SONG OF SONGS, RUTH, ESTHER, JONAH, AND DANIEL

A Translation with Commentary

ROBERT ALTER

Adjusting type size may change line breaks. Landscape mode may help to preserve line breaks.

for

Carol,

my one and only love

CONTENTS

T HESE FIVE TEXTS are generally classified by scholars as Late Biblical books. Late Biblical Books is by no means a rubric under which texts have been placed in any of the formulations of the biblical canon. The foundational books of the Hebrew Bible were composed (though not yet edited) from the tenth or ninth to the seventh century BCE, with only a few archaic poems coming from an earlier period. The watershed of biblical history was the Babylonian exile, which began after the conquest of Judah and Jerusalem in 586 BCE. Some great prophetic poetry was written in the exile during the sixth century, but its strong stylistic and thematic continuities with pre-exilic writing preclude the classification of late for these texts. There were also some psalms written around this time that were included in the canonical collection and probably at least a few proverbs. Late Biblical literature, showing marked differences from the Hebrew writing of the First Commonwealth, was produced from the fifth to the second century BCE, some of it the work of writers in the diaspora, by then under Persian domination, and some of it in the Land of Israel. The two most original and theologically challenging books of Late Biblical literature are Job and Qohelet, both of which I have translated with commentary in a volume entitled The Wisdom Books . The short books presented here are, even in their brevity, artful and innovative literary works (perhaps with the exception of Daniel)beguiling, entertaining, and in some instances perhaps a bit startling.

How do we know that they are late? Esther is manifestly set in the Persian court, as is, retrospectively, Daniel; and Ruth, though it purports to be a story that takes place in the period of the Judges, is concerned with the question of exogamy that much exercised the community in Judah in the mid-fifth century BCE but that was not a pressing issue in earlier times. Beyond any such thematic considerations, the great hallmark of lateness, showing variously in all five of these books, is linguistic.

Biblical Hebrew, like any language, changed through time. The temporal distance between the sundry strands of Genesis or the Book of Samuel and these Late Biblical texts is comparable to the distance between Shakespeare and John Updike. Just as in the four centuries separating Shakespeare from Updike the English language underwent pronounced changesterms once in common usage replaced by others, palpable modifications of grammar and syntaxthe Hebrew through these centuries exhibits a similar set of changes. One of the books in this volume, Ruth, because it purports to take place in the period before the founding of the monarchy around 1000 BCE, deploys an archaizing style that is meant to sound like the literary Hebrew of that era. Flawless archaizing, however, is a very difficult feat to pull off, and so there is a series of small slips, perhaps as many as a dozen, where a word or idiom is used that appears only in Late Biblical Hebrew, never earlier. The Late Biblical character of the Hebrew of Jonah and Esther is more straightforward: one encounters grammatical usages, idioms, and primary items of vocabulary that are distinctively Late Biblical, some of them reflecting the Aramaic that was becoming dominant, and Esther also abounds in Persian loanwords. The Hebrew of the Song of Songs is less overtly late, probably because of the tendency of poetry to be stylistically conservative, but even here there are a few grammatical features and some terms that would not have occurred in the Hebrew in literary usage before 586 BCE.

The Hebrew of the Book of Daniel is surely the oddest instance of linguistic lateness. Roughly the first half of the book, beginning early in Chapter 2, is written in Aramaic. (The only other extended Aramaic section in the Bible is four chapters in the Book of Ezra.) The Aramaic seems perfectly serviceable though not stylistically distinguished, showing, as it does, a strong tendency to formulaic language and mechanical repetitions. Chapter 7 to the end of the book is written in Hebrewprobably because Hebrew is the language of prophecy with which the author (or authors) sought to align his (or their) own work. In keeping with the aim of sounding prophetic, the writer tries to avoid overtly Late Biblical turns of language. It looks suspiciously, however, as if Hebrew were not a vehicle with which he is entirely comfortable: idioms get mangled, terms are sometimes used in problematic senses, and the syntax in a good many instances is awkward or actually garbled. What we have, then, in the Hebrew of Daniel is a Late Biblical writerindeed, the latest of biblical writers, active, as one can tell from his historical references, in the fourth decade of the second century BCEwho labors to place his own literary production in a Hebrew tradition that goes back to the era before the Babylonian exile but does not succeed very well.

It has often been observed that this late period gave rise to writing that diverged in its views or openly dissented from the biblical texts of the First Commonwealth era. The impulse of dissent is most strikingly evident in the challenges to mainstream biblical ideas laid out in Job and in Qohelet. In the books in this volume, the celebration of erotic love in the Song of Songs and the carnivalesque spirit of Esther, both devoid of theological concerns, are altogether unlike anything found in the antecedent Hebrew literature that has come down to us. What should be added to this common observation about Late Biblical writing is that it reflects a vigorous exploration of new literary forms, and that will be a recurrent focus of the commentary which accompanies these translations. Hebrew narrative before the Babylonian exile is by and large formally conservative. There are some stylistic as well as ideological differences among the four principal strands that make up the Pentateuch, but all these writers share common assumptions (and common literary conventions) about how to tell a story and the purposes to be served by the stories. Nor are there significant differences in these regards between the Pentateuch and the sundry narratives that constitute the Deuteronomistic History, the stretch of books from Joshua to the end of Kings.

By contrast, the works composed from the fifth to the second century BCE reflect an extraordinary efflorescence of new literary genres and techniques. Ruth, which by the authors design seems closest to earlier Hebrew writing, is nevertheless a new kind of narrativea bucolic idyll in which the profound elements of conflict and ambiguity that define classical Hebrew narrative are rigorously excluded, and the prose itself, with its repeated use of balanced cadences approximating poetry, expresses the harmony of the idyllic world. Jonah, though it purports to be the story of a prophet, deploys fantastic elements to shape a fable about the prophetic calling, making these elements seem different in kind from the stories of miracles that occasionally punctuate earlier Hebrew narrative. Esther is a different kind of fantasy, one of national triumph over powerful forces, which does not employ supernatural intervention. It is cast in a satiric mold that incorporates farce and is at moments even raucous. This writers fondness for the descriptive details of imperial pomp is nothing like antecedent Hebrew literature; and above all, it is a story framed for sheer entertainmentwhich goes along with its often-noted lack of reference to God, Torah, or the Land of Israel. In this crucial regard, it is a kind of story that would have been inconceivable for the writers of the First Commonwealth. Daniel is generically distinct from all its literary antecedents in being an apocalyptic book: in its pages, prophecy has been transformed into the deciphering of enigmatic coded visions that indicate precisely what will happen and when it will happen in an inexorably deterministic system leading to an end-time. And the Song of Songs is a collection of exuberant love poems exulting in the delights of the sensesagain, with no mention of Godthat puts aside all the concerns of earlier Hebrew literature with covenant, Torah, and the history of Israel (though allegorical interpretation would put all these back into the Song). Scrutiny of earlier biblical textssee especially Isaiah 5suggests that there was a genre of Hebrew love poetry centuries before the Song, but it surfaced only at this late moment, perhaps in part because of the sense of freedom that later Hebrew writers felt to express themselves in genres strikingly different from the ones that had till then defined the literature of the emerging canon.

Next page