Acknowledgments

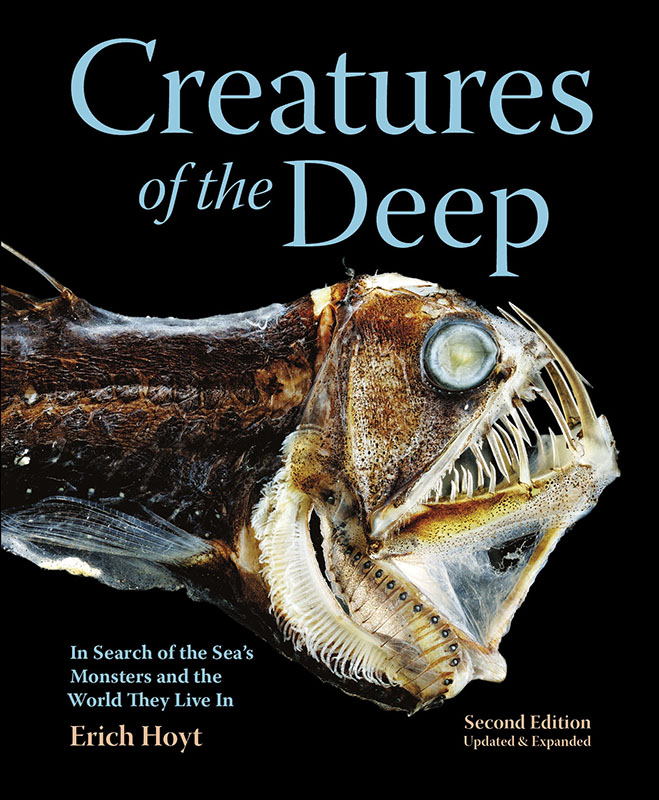

The widespread interest in the first edition of this book and in other books exploring the deep sea has made it easy to generate enthusiasm to produce this revised edition with updated and greatly expanded text, the latest photographs and a new design.

First, I must thank the scientists who are slowly uncovering the secrets of these deep-sea creatures. For without the steady procession of new discoveries, there would be no need for another journalistic expedition across the ocean expanses and to the deepest waters of our planet. In essence, we all need to thank the creatures themselves for inspiring such wonder and for turning up at a surprisingly steady rate year after year2,000 new species per year since 2000.

In addition, I would especially like to thank two of my favorite editors, Tracy C. Read and copy editor Susan Dickinson, along with Lionel Koffler and Michael Worek at Firefly, for making this book possible. All were involved in the first edition of Creatures of the Deep, so there is a strong continuity. I would also like to thank Fireflys Pippa Kennard for coordinating the photos and for facilitating every aspect of the books production, designer Hartley Millson, illustrator George A. Walker, indexer Gillian Watts and all the photographers, especially David Shale, for his unfailing help with background details on his deep-sea images, and Sandra Storch, who provided the background for Solvin Zankls photos. Erika Fitzpatrick provided enormous help with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution images. I owe my passion and some of my thinking on biodiversity, protected areas and whale conservation in the books final section to a number of friends and colleagues, including Tundi Agardy, Jeff Ardron, Regina Asmutis-Silvia, Brad Barr, Mike Bossley, Alexander Burdin, Chris Butler-Stroud, Sarah Dolman, Nicolas Entrup, Ivan Fedutin, Olga Filatova, Naoko Funahashi, Kristina Gjerde, Nicola Hodgins, Miguel Iguez, Tanya Ivkovich, Kristin Kaschner, David Mattila, Naomi McIntosh, Cara Miller, Mikhail Nagaylik, Peter Poole, Margi Prideaux, Patrick Ramage, Randall Reeves, Lorenzo Rojas Bracho, Mark Simmonds, Liz Slooten, Brian Smith, Michael Tetley, Vanesa Tossenberger, Jos Truda Palazzo Jr., Rob Williams, Vanessa Williams-Grey, Edward O. Wilson, Alison Wood and especially my fellow chair of the IUCN Marine Mammal Protected Areas Task Force, Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara. I would like to express my deepest appreciation to biological oceanographer Paul Snelgrove at Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, who read the entire text and provided excellent suggestions and corrections. In addition, Charlie Huveneers provided valuable comments on the sections about sharks. Of course, any errors that remain are my own.

Our passion and belief in this edition comes from the ocean itself and the desire to share new insights into this strange, deep world.

Erich Hoyt

Bridport, Dorset, England

May 2014

CONTENTS

The acorn worm, or enteropneust (Yoda purpurata), which feeds on seafloor sediment, was discovered in 2010 above the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and named in 2012. The enteropneust shares anatomical features of both invertebrates and vertebrates. Some evolutionary biologists think it may have given rise to the vertebrates.

Author's Note

You thought I should find nothing but ooze and Ive discovered a new world!

H. G. Wells, Into the Abyss

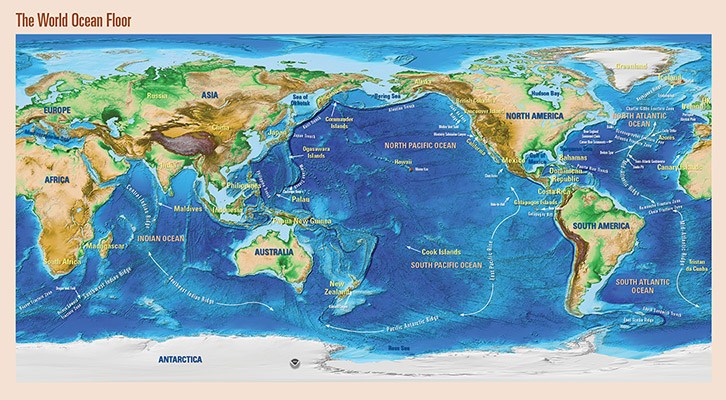

I N 2001, when the first edition of Creatures of the Deep was published, I wrote that we were embarking on a great century of discovery in the deep ocean. That prediction is on course. In 2007, fishermen off New Zealand hauled to the surface the largest colossal squid ever seen by humans (though still never observed alive in its natural habitat). In 2010, researchers reported on the Census of Marine Life, a decade-long investigation into life in the oceans that described some 6,000 potential new species, mainly in the deep sea. Soon after that announcement, scientists raised the estimated number of oceanic species named and known to science from 220,000 to 240,000, an increase of 20,000 new species that make their homes in the sea. Thanks to an expedition that launched from Japan in June 2012, we were able to watch the first video of a living giant squid in the wild. Also in 2012, after a gap of 50 years, we shared the excitement of the second manned visit to the deepest spot in the oceanChallenger Deep, at the southern end of the Mariana Trenchundertaken by filmmaker James Cameron.

Theres much, much more. For example, in 2006, on the North Icelandic Shelf near Grmsey Island on the Arctic Circle, researchers from Bangor University in Wales dredged up what they took to be 400-year-old specimens of the clam Arctica islandica. The age of one of the clams was subsequently determined to be 507 years, which was confirmed by carbon dating. The longest-lived noncolonial animal with an accurately determined life span, this clam was named Ming, a tribute to the fact that it had started life during the Chinese Ming Dynasty. While there is no way of knowing just how much longer Ming might have lived had the clam been left on the ocean floor, its discovery does lead us to wonder what secrets to a long and happy life are to be found in the cold waters north of Iceland.

Around the deep-sea hydrothermal vents, researchers have discovered the scaly-foot snaila gastropod with a hard-shell foot adapted to withstand hot conditionsand the furry abominable crab, also known as the Yeti crab. Found in the South Pacific Ocean in 2005, this crab has a fur coat, which seems strangely out of place for a creature living near a site where supercritical water (whose physical properties lie between those of a gas and a liquid) pours out from the hottest parts of the vents at temperatures up to 867 degrees F (464C). And there is not just one Yeti crab but several and perhaps many; different species appear to live at different hydrothermal vents.

Yeti crabs have also been discovered at so-called cold vents, or cold methane seeps, where water transports dissolved elements from the seabed. Oregon State Universitys Andrew Thurber and his colleagues uncovered a notable new Yeti species, Kiwa puravida, during an Alvin submarine cruise off Costa Rica in 2006. A microbe specialist, Thurber studied how the new Yeti rhythmically swings its chelipeds, or claws (which are covered in dense setae and epibiotic bacteria), above the methane seep in what appears to be a form of symbiosis with the bacteria. These Yeti are thought to farm the bacteria, caring for them, nurturing them and perhaps consuming them, much like the ants that stand guard over subdued aphids, feeding from their sugary secretions and, as needed, eating the aphids.