The Sciences

by

Edward S. Holden

Yesterday's Classics

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Cover and Arrangement 2010 Yesterday's Classics, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or retransmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

This edition, first published in 2010 by Yesterday's Classics, an imprint of Yesterday's Classics, LLC, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Ginn and Company in 1927. This title is available in a print edition (ISBN 978-1-59915-338-4).

Yesterday's Classics, LLC

PO Box 3418

Chapel Hill, NC 27515

Yesterday's Classics

Yesterday's Classics republishes classic books for children from the golden age of children's literature, the era from 1880 to 1920. Many of our titles are offered in high-quality paperback editions, with text cast in modern easy-to-read type for today's readers. The illustrations from the original volumes are included except in those few cases where the quality of the original images is too low to make their reproduction feasible. Unless specified otherwise, color illustrations in the original volumes are rendered in black and white in our print editions.

Preface

The object of the present volume is to present chapters to be read in school or at home that shall materially widen the outlook of American school children in the domain of science, and of the applications of science to the arts and to daily life. It is in no sense a text-book, although the fundamental principles underlying the sciences treated are here laid down. Its main object is to help the child to understand the material world about him.

All natural phenomena are orderly; they are governed by law; they are not magical. They are comprehended by some one; why not by the child himself? It is not possible to explain every detail of a locomotive to a young pupil, but it is perfectly practicable to explain its principles so that this machine, like others, becomes a mere special case of certain well-understood general laws.

The general plan of the book is to waken the imagination; to convey useful knowledge; to open the doors towards wisdom. Its special aim is to stimulate observation and to excite a living and lasting interest in the world that lies about us. The sciences of astronomy, physics, chemistry, meteorology, and physiography are treated as fully and as deeply as the conditions permit; and the lessons that they teach are enforced by examples taken from familiar and important things. In astronomy, for example, emphasis is laid upon phenomena that the child himself can observe, and he is instructed how to go about it. The rising and setting of the stars, the phases of the moon, the uses of the telescope, are explained in simple words. The mystery of these and other matters is not magical, as the child first supposes. It is to deeper mysteries that his attention is here directed. Mere phenomena are treated as special cases of very general laws. The same process is followed in the exposition of the other sciences.

Familiar phenomena, like those of steam, of shadow, of reflected light, or musical instruments, of echoes, etc., are referred to their fundamental causes. Whenever it is desirable, simple experiments are described and fully illustrated,

and all such experiments can very well be repeated in the schoolroom.

Finally, the book has been thrown into the form of a conversation between children. It is hoped that this has been accomplished without the pedantry of Sandford and Merton (although it must be frankly confessed that the principal interlocutor has his knowledge very well in hand for an undergraduate in vacation time) or the sentimentality of other modern books which need not be named here. The volume is the result of a sincere belief that much can be done to aid young children to comprehend the material world in which they live and of a desire to have a part in a work so very well worth doing.

| NEW YORK CITY, January, 1903 |

Contents

Introductory Chapter

(To Be Read by the Children Who Own This Book)

L ET me tell you how this books came to be written. Once upon a time, not so very long ago, a lot of children were spending the summer together in the country. Tom and Agnes were brother and sister and were together all the day long; bicycling or playing golf in the morning, reading or studying in the afternoon. The people who lived in the village used to call them the inseparables because they were always seen together during their whole vacation from June to September. Their cousins Fred and Mary always spent a part of every summer with them; and when they came there were four inseparables , not two. The children liked the same games, liked to read the same books, to talk about the same kind of things, and so they got on very well together; though sometimes the two boys would go off by themselves for a hard days tramp in the hills, or to shoot woodchucks, or for a very long bicycle ride, leaving their sisters at home to play in the garden with dolls, or to do fancywork and embroidery, or to play tennis, or to read a book together. Tom was thirteen years old then, and his sister Agnes was nine; cousin Fred was ten and his sister Mary was twelve.

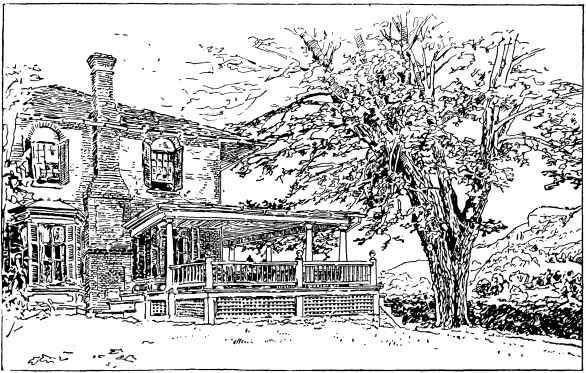

When the summer afternoons began to get very warm, in July, a rule was made that the children should spend them in the house, or on the wide, shady porch, or else under the trees on the lawn, or in the garden. Golf, tennis, and wheeling had to be done in the morning; the afternoons were to be spent in something different. Tom's father used to say that the proverb

All work and no play

Makes Jack a dull boy

was only half a proverb. It was just as true, he said, that

All play and no work

Makes Jack a sad shirk.

And so a part of every summer afternoon was given up to reading some good book, or to study, or to work of some sort. The two boys had their guns and wheels to keep thoroughly bright and clean, and a dozen other things of the sort; the two girls had sewing to do; and all of them together agreed to keep the pretty garden free from weeds.

Almost any afternoon you might see the four inseparables tucked away in a corner of the broad piazza, each one busy about something, and all talking and laughingexcept, of course, when one of them was reading, and the others paying good attention. Tom's big brother Jack was at home from college, and in the afternoons he was almost always on the porch reading, or else on the green lawn lying under the trees; and Tom's older sisters, Mabel and Eleanor, were there too, sewing, or embroidering, or reading, or talking together.

So there were two groups, the four childrenthe inseparablesand the three older ones. When the children came to something in their book that they did not quite understand, Tom would call out to his big brother Jack to explain it to them, and Jack would usually get up and come over to where the children were and tell them what they wanted to know. Almost every day there were conversations of the sort, and explanations by some one of the older ones to the four children. All kinds of questions would come up, like these:

THE PORCH

"Jack, tell us why a 'possum pretends to be dead when he is only frightened and wants to get away."

"Jack, tell us why a rifle shoots so much straighter than a shot-gun or a musket."