BASH Guide

FICTION BOOKS BY JOSEPH D E VEAU

Threads of Fate

Shadowborn

LINUX BOOKS BY JOSEPH D E VEAU

BASH Guide

BASH Guide

JOSEPH D E VEAU

BASH Guide by Joseph DeVeau

The author and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contains herein.

Trademarked names appear throughout this book. Rather than use a trademark symbol with every occurrence of a trademarked name, names are used in an editorial fashion, with no intention of infringement of the respective owners trademark.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

Copyright 2016 by Joseph DeVeau

www.josephdeveau.com

Cover Artwork by JD Bookworks

Published by JD Bookworks

ISBN-978-0-9963376-5-6

First Edition: May 2016

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

FOR THE DREAMERS OUT THERE,

the loftiest dream requires the most solid foundation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A big thanks to my outdoor-loving black lab, Ranger, who pulled meoften quite literallyoutside when my eyes glossed over and the simplest Hello World script looked like gibberish.

BASH Guide

Introduction

Motive

Why, when there are numerous coding resources already, did I write this guide? The answer is simple: examples. I have always learned best by studying examples. This is a guide for those out there like me that need to see a task performed before they can properly emulate it.

Other guides take different approaches. At best, the high level language and purely general cases used throughout textbook-like resources are mind-numbingly dry. At worst, they hamper learning. On the flipside, the attempt of some guides to provide a beginner friendly introduction to the material take such a lofty view that any practical details regarding the how are lost to flow diagrams and lengthy explanations of the why .

This guide attempts to bridge the gap between the two; to provide enough of the what and why so the real-world how has context. Thus, explanations are typically short and followed by numerous examples.

Do not attempt to memorize every detail presentedminute details are easily forgotten, and just as easily looked up. Rather, attempt to understand how each of the examples functions. All syntax tables and generalized cases have been reproduced at the end to create a Quick Reference that can be turned to when details inevitably fall by the wayside.

Audience background

No programming, coding, or scripting knowledge is necessary for the reading or understanding of this guide. As a matter of fact, no knowledge of the Linux operating system or terminal itself is required. That said, of course any previous languages, experience, or technical knowledge will hasten the speed at which the information presented is acquired.

Formatting

The formatting used throughout the guide has been standardized. The first use of important concepts are in bold . Commands, arguments, parameters, filenames, paths, and similar terminology are italicized .

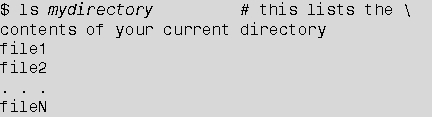

Code, scripts, command-line input, and the output for all of them are contained within code blocks. Typically, code can be entered into your own terminal verbatim. Exceptions are items such as yourfile , my_domain , and others, which should be replaced with the entry relevant to your system, working directory, input or data file, etc.

Anything proceeded by a hash mark, # , is a comment and should not be entered (though you may enter it if you choose; it will have no effect). A backslash, \ , allows code to be continued on the next line without it being broken by a newline.

Output of more than a few lines will typically be truncated by an ellipsis (...).

Chapter 1: History

Early interfacing with computersin the post wire-plug and punch-card erawas accomplished by entering text commands into a command-line interpreter. The function of this command line interpreter , or shell , is to talk to the underlying operating system. At the heart of the shell is the kernel, which talks to physical devices such as printers, keyboards, mice, and monitors, through their various drivers. Thus, through the use of a shell, a user can control, execute, and automate virtually any task a modern computer is capable of performing.

Shells

The first shell was the Thompson shell , written by Ken Thompson. Due to the limitations of the systems at the time, it was simply called sh . After nearly a decade of use, it was ousted by the more feature-rich Bourne shell , written by Stephen Bourne. To make things confusing for the techies of that era, he kept the same name, sh . It would take a bit more than another decade before the Bourne shell was overtaken by thewait for it Bourne-again shell , or Bash .

Bash

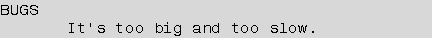

Though originally released in 1989, Bash has been through a long series of updates, upgrades, and revisions, each of which gave it access to ever-more useful and powerful tools. Additionally, as utilities were developed to handle certain tasks, or other competing shells released new features, Bash integrated many of them into itself. As of this writing, Bash is on version 4.3. Its man page (manual page), consists of more than fifty-seven hundred lines, and near the very end contains the following (almost comical) line.

Other shells

Although many other shells exist, such as csh , ksh , and zsh , this guide assumes you are using Bash . Note that you can use this guide without having access to a Bash shell. You will however, need to be aware that not everything described in this book is portable; that is, a script that runs in Bash will not necessarily function correctly (or at all) in another shell, or vice-versa. [[ is a prime example of this. Do not despair though! All the concepts, from variables and arrays to conditionals and loops, are transferrableyou may simply need to learn a little shell-specific syntax.

You can check which shell you are using by issuing the following command, which prints the $SHELL environment variable.

If your computer is using something other than /bin/bash , you can change your default shell to Bash (provided of course Bash is installed on your system) by issuing one of the commands below.

The first sets the shell for a particular user (change username to reflect your username, i.e. the output of whoami ) in the configuration file, /etc/passwd . The second sets the shell for the currently logged-in user upon login through the use of that users ~/.profile configuration file.

![Chris F.A. Johnson [Chris F.A. Johnson] - Pro Bash Programming: Scripting the GNU/Linux Shell](/uploads/posts/book/119669/thumbs/chris-f-a-johnson-chris-f-a-johnson-pro-bash.jpg)