HARNESSING THE POWER OF GOOGLE

What Every Researcher Should Know

Christopher C. Brown

Copyright 2017 Christopher C. Brown

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Brown, Christopher C., 1953 author.

Title: Harnessing the power of Google : what every researcher should know / Christopher C. Brown.

Description: Santa Barbara, California : Libraries Unlimited, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC, [2017] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017007461 (print) | LCCN 2017021554 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440857133 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440857126 (acid-free paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Google. | Internet searching. | Internet research. | Libraries and the Internet. | Internet in library reference services.

Classification: LCC ZA4234.G64 (ebook) | LCC ZA4234.G64 B76 2017 (print) | DDC 025.04252dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007461

ISBN: 978-1-4408-5712-6

EISBN: 978-1-4408-5713-3

212019181712345

This book is also available as an eBook.

Libraries Unlimited

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911

Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911

www.abc-clio.com

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

Figures displaying Google Web site materials are 2015 Google, Inc., used with permission. Google and the Google logo are registered trademarks of Google, Inc.

Contents

Illustrations

FIGURES

TABLES

Introduction

Why is a reference librarian writing about using Google for academic research? Dont professors tell students not to use Google in their research? Isnt Google a threat to librarianship, and wont it eventually replace the need for librarians? This book will suggest that Google is extremely valuable in the academic research process, but users need to understand what is being searched, how to constrain searches to academically relevant resources, how to evaluate what is found on the Web, and how to cite what is found.

Its not uncommon for new university students to think they already know how to search. Their first paper comes due, and what do they do? They resort to using Google. They think they know it allor at least where everything can be found. But when they get that first paper back with an unsatisfactory grade and comments like, you need to cite peer-reviewed articles, dont rely on Google, and you need reliable sources to support your arguments, many of them show up for research consultations and to meet with reference (research) librarians. It takes a librarian to really show them how to search.

Ill let you in on a little secret: all reference librarians, academic or otherwise, use search engines, especially Google. The extent to which it is used varies, of course, but Google can be the single best starting point for navigation down the right path. When someone has a question, they dont know the answer. This seems obvious, but it is profoundly important. If someone doesnt know something, they may not even know how to visualize what the answer looks like or what path to pursue. Trying to navigate in a fog is nearly impossible. But Google is there to correct our misspellings, suggest new pathways, and clear the fog.

This book is not intended to cover every feature of Google. We intentionally gloss over Google Earth, most of the Google widgets, Google personalization features, linkages to Google+ and other Google properties, and even some of the search capabilities that have little to do with academic research. This is intentional. Many books already do that. All you have to do is search Google Web like this: how to search google , or Google Books like this: how to search google . This book is focused on assisting students, researchers, teachers, professors, and librarians in finding primary and secondary sources using Google.

Searching Generally

The history of language, writing, and indexing is a fascinating one. When thinking of how we access the vast libraries of information that exist in the world, we must remember that before the writing of literate cultures there were oral cultures. These cultures had ways of remembering or indexing in the mind as well. Long gone are the days when scholars would memorize long texts and be able to search their memories for ideas and arguments. Since Gutenbergs printing press and the printing revolution, publications have proliferated and various finding aids, including bibliographies, printed indexes and catalogs, card catalogs, and, more recently, online catalogs and indexes, have been created to provide intellectual access to print publications. To fully appreciate the technology available to us today, we need a bit of historical perspective.

HISTORY OF SEARCHING

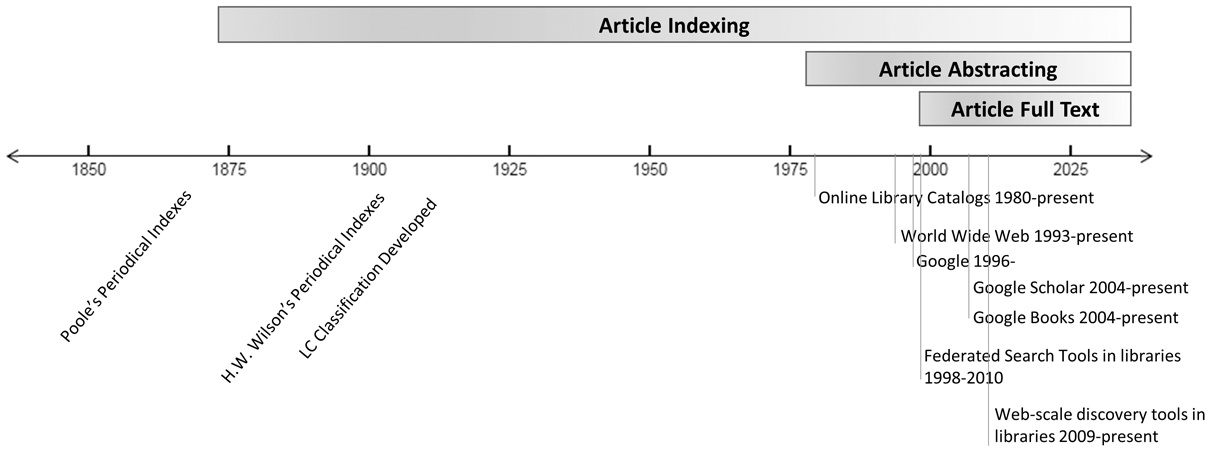

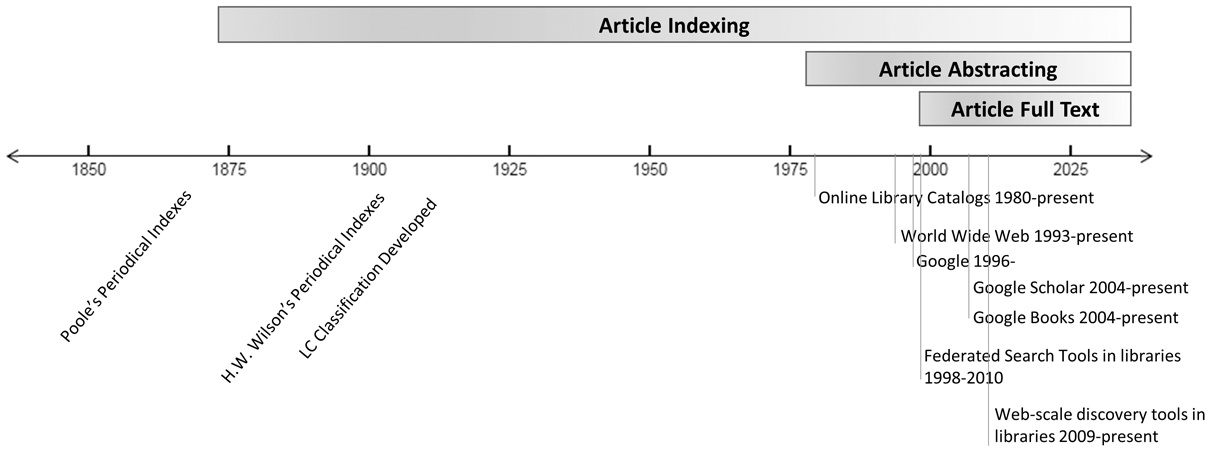

The blossoming of magazine and journal publishing soon necessitated a way to discover all this content. Thus modern indexing was born. A glance at a technology timeline will help give us a historical perspective (see ). The mid-1800s saw the beginning of periodical indexing with pioneers like William Frederick Poole and H. W. Wilson. Pooles Index to Periodical Literature , published in the mid-1800s through various editions and supplements, economized space with abbreviations and small print and was tedious and challenging to use, but it worked. Wilson, whose work endures to this day, also saved space with abbreviations, but incorporated a technology that was being developed in his day: subject headings along the lines of Library of Congress subject headings.

Some of our older readers will remember libraries with card catalogsthose handsome wooden cabinets with tiny drawers to accommodate cards with information about the books or other materials owned by the library. The most common scheme for library card searching was the dictionary catalog approach: cards arranged alphabetically for authors, cards for subjects, and cards for titles. But it gets more complex that just these three simple categories. When there are multiple authors or editors, another card set needs to be created. Every subject assigned generates more card sets. Title cards would account not only for the main title, but also for additional titles such as series titles, varying forms of the title, translated title, etc.

FIGURE 1.1.Key Events in Recent Searching History.

There was no keyword searching in the physical library catalog days. Access, at least for English language materials, was left-anchored. That is, searchers had to start from the left to look up an author, subject, or title. If an authors name was Christopher C. Brown, the name was inverted phonebook style to Brown, Christopher C. Subjects were governed with controlled vocabularies such as the Library of Congress subject headings. Titles had special considerations as well. Users had to omit initial articles (for English, omitting a , an , or the from the beginning of titles). This greatly inhibited the access to materials, but because that was the state of the art at that time, users didnt know what the future held.

Next page