AND SOME FELL ON STONY GROUND

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF AN RAF BOMBER PILOT

A Fictional Memoir by LESLIE MANN

With an Introduction by Richard Overy, author of The Bombing War

Published in the UK in 2014 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

3941 North Road, London N7 9DP

email:

www.iconbooks.com

Published in association with Imperial War Museums

iwm.org.uk

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

7477 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by

Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India,

11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi 110017

ISBN: 978-184831-720-8

Text copyright Christopher Mann and Anthony Mann 2014

The Estate of Leslie Mann has asserted its moral rights

Introduction copyright Richard Overy 2014

Richard Overy has asserted his moral rights

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher

Typeset in Berling by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

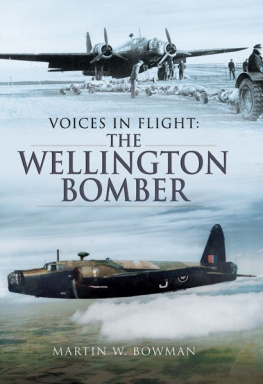

List of illustrations

About the author

LESLIE MANN was born in Singapore in 1914, the son of a police inspector. The family later moved to the UK, and Leslie started work as a sound engineer at Elstree Studios. He enlisted in the RAF in 1939, and married in 1940.

Ultimately stationed near Ripon, Yorkshire, he served as a Flight Sergeant rear gunner with No. 51 Squadron, RAF Dishforth, operating Armstrong Whitworth Whitley twin-engine bombers. He was shot down on a raid over Dsseldorf on the night of 19/20 June 1941, the only loss from twenty aircraft on that raid: all five crew were captured.

Unusually, Mann was repatriated to the UK in October 1943 and discharged from the RAF in 1944. He worked for Path News and later became a correspondent in the Korean War and a cameraman in Kenya during the Mau Mau uprising. He then moved to the BBC, for whom he worked as a senior news executive until retirement. He died in 1989.

RICHARD OVERY is an award-winning historian best known for his remarkable books on the Second World War and the wider disasters of the twentieth century. His most recent book, The Bombing War, was described by Richard J. Evans in The Guardian as: Magnificent must now be regarded as the standard work on the bombing war It is probably the most important book published on the history of the second world war this century. He is Professor of History at the University of Exeter and lives in London.

Authors note

This story is an attempt to explain through an airmans mind his last twelve hours on a bomber station.

After the fall of France in 1940, Britain had to concentrate on fighters and defences, and Bomber Command operated as best it could, mainly for nuisance value and home propaganda. The leaflet raids had stopped and bombing started in earnest. Discipline for aircrews was by no means rigid, aircraft rather outdated, and losses were high. Operations were carried out, it seemed, by trial and error, while the New Air Force was being built up.

This is not a story of heroes; of men who groaned with disappointment when an op was postponed or cancelled; of men who smuggled themselves out of hospital so as not to miss going with their crew on a particular raid; although, no doubt, there were men like that in the Royal Air Force.

I have tried to give a picture as I saw it.

Leslie Mann

And some fell on stony ground, where it had not much earth; and immediately it sprang up, because it had no depth of earth:

But when the sun was up, it was scorched; and because it had no root, it withered away.

Mark, 4: 5,6

Introduction

By Richard Overy

The anti-hero of Leslie Manns fictional representation of RAF Bomber Commands offensive against Germany finds that his first thought on landing by parachute on German soil after his aircraft has been hit by anti-aircraft fire is simply No more ops. This is perhaps not the popular version of the story of the heroic bomber crew who night after night ran exceptional risks over Europe, but it reflects a profound reality. For those young men who had to go over the top night after night, the strain of a prolonged tour of operations was profound. This short fictional account conveys better than a hundred dry operational reports the fear and the courage that jostled side by side in the mind of almost every bomber crewman.

It is important to emphasise that this is a fictional but not a fictitious account. The details of daily life on a bomber base and the vivid description of a bomber operation were the product of a lived experience. Leslie Mann flew as a tail gunner in Whitley medium bombers and was shot down over Germany in June 1941, just like his fictional Pilot Officer Mason. He joined the Royal Air Force in 1939, when it was still in the slow process of converting to more modern aircraft types. He ended up in Bomber Command, formed in 1936 when the RAF was restructured on functional lines, separating fighters, bombers and coastal defence aircraft. No one knew when the war broke out on 3 September 1939 what bomber crew would be expected to do. Bombing operations were confined to occasional forays against the German fleet; bomber crew found themselves flying over hostile territory dropping propaganda leaflets. Bombing enemy home front targets was prohibited.

All this changed in May 1940. As the German invasion of France and the Low Countries got under way from 10 May, the new Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, discussed with his cabinet the prospect of bombing German industrial and communications targets to try to slow up the German advance and to divert the German Air Force to home defence. On the night of 11/12 May, 37 bombers attacked rail and road targets in the town of Mnchengladbach. The operation included eighteen Whitleys, one of which was shot down. Despite optimistic expectations of both the material damage and the morale effect, the bombing achieved very little. German observers were puzzled about the purpose of it, since the attacks were wildly inaccurate, many of the bombs falling in the open countryside. At night with no electronic navigation aids, and a comprehensive blackout to combat, it proved very difficult to find even the city where the targets lay. The German air defence concluded that the British pilots had been instructed to drop their bombs to cause maximum damage to civilians and civilian housing.

The RAF continued to bomb German targets all through the Blitz period with an increasing weight of bombs, but the operational difficulties undermined the efforts made by bomber crews to try to find and hit the targets they were ordered to bomb. In October 1940 they were instructed to hit anything that looked militarily useful if they could not find their primary target. Slowly the RAF commanders realised that with the existing technology and tactics there was no prospect of inflicting anything like decisive damage on German industry. By July 1941, shortly after Leslie Mann was shot down, the decision had been made to focus attacks on the morale of the German workforce by bombing industrial city areas. This decision was taken long before Air Marshal Arthur Harris took over the Command in February 1942, though he is still widely, and wrongly, regarded as its instigator. A few weeks later in August 1941 Churchills chief scientific adviser, Frederick Lindemann (later Lord Cherwell), published a report produced by one of the statisticians on his staff, David Butt, which showed that over the Ruhr-Rhineland industrial region only one aircraft in ten got within five miles of the designated target. Leslie Mann would certainly have understood that this was the reality of the many missions he had flown. In a note at the start of his manuscript he observes that the operations he and his fellow crewmen undertook had only nuisance value.

Next page