This book is dedicated to all the former members of the Manchester Bomber Command Association, especially Norman Jones, Jim Gardner and Alan Morgan, whose friendship I have treasured over the many years that I have known them.

Also to the memories of Stan Walker and Bryan Wild, two former RAF pilots, who over the years became great friends and shared many memories with me. The spirit and humility of all those mentioned above is typical of their generation, claiming that what they did in the Second World War was just a job that had to be done.

C ONTENTS

Due to ill health and various other problems this book has been a long time in the making, but hopefully the information gathered over the last few years enhances what is probably one of the last stories to come out of the Great War. For that I have to especially thank Captain Vickers niece, Christine Farrell, his nephew, Michael Pratt, and his namesake, Stephen Vickers.

In 1998 I visited 101 Squadron at Brize Norton for the first time and was shown around by Flight Lieutenant Gary Weightman, who has written his own short version of the squadrons operations entitled Lions of the Night. He has carried out considerable research into the squadrons activities during the Great War and his account and enthusiasm to record the squadrons history was a great inspiration.

Over ten years later, in June 2009, I was invited to visit Brize Norton again and on that occasion I was the guest of Flying Officer Jim Dickinson for the day. Some of the details of that visit are mentioned in the final chapter, but I would like to thank Flying Officer Jim Dickinson, Flight Lieutenant McFarland, Sergeant Paul Riley and Squadron Leader Curry. I would especially like to thank the commanding officer of 101 Squadron, Wing Commander Tim OBrian, who made it all possible.

With huge cuts having been made in personnel, I understand that it is quite difficult for RAF units to accommodate requests for visits by individual civilians and organisations. However, the staff of 101 Squadron and RAF Brize Norton showed not only the kind of hospitality that might be expected of them, but went out of their way to ensure that I got all the information I required and that my visit was worthwhile.

There are many other individuals who have at one time or another been involved with this project, amongst them researchers Norman Hurst, John Williams, Tim Tilbrook and John Eaton from Stockport Heritage Trust, and the 101 Squadron secretary, Squadron Leader G.G. Whittle DFM (Retired).

Finally I would like to thank Arthur Lane, Norman Hurst and Tony Harman (Kodak franchise, Skipton) for helping to sort out and process many of the photographs that appear in this book. Due to their age, some of them needed to be enhanced and without their help the images would not have been suitable for publication.

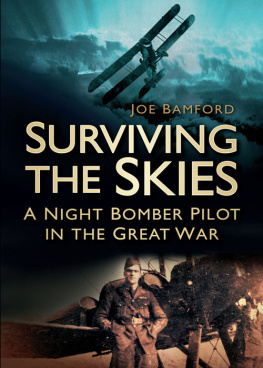

T his is the remarkable story of Captain Stephen Wynn Vickers MC, DFC, an exceptionally talented airman but whose exploits and experiences have been overshadowed by the passing of time. Surviving the Skies is a detailed account of the circumstances that led up to Captain Vickers joining the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and how he learned to fly. It also describes how he acquired the essential skills that allowed him to operate in one of the RFCs most dangerous and specialist roles of night bombing.

It was Captain Vickers niece, Christine Farrell, who first brought him to my attention while I was getting some photographs copied for my first book, The Salford Lancaster. With her late husband Brian, who was a chemist, she worked as a dispensing technician in the local pharmacy and, having taken an interest in my photographs, told me that she had some of her late uncle who had been a pilot during the First World War. When Christine queried whether I would like to see them, there was no need for her to ask twice!

I was fascinated to see a number of photographs of her uncle posing by the side of a BE2c at Haggerston, an airfield in north-east England, and to learn that he had been awarded both the Military Cross (MC) and the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). Further research and a visit to the National Archives (formerly the Public Records Office) revealed that Captain Vickers had played a leading role on 101 Night-Bombing Squadron. He had been a founding member of the squadron and his exploits were well documented there, but like many others, in relation to the history of the RFC, he had been overlooked with the passage of time.

Christine Farrell also gave me access to other photos and family documents, and I soon discovered that Captain Vickers log book and records were in the possession of his nephew, Michael Pratt, who lives near Bristol. Michael was very co-operative and gave me a copy of his uncles log book, along with many other items that formed the basis of this account of his service with the RFC.

The story, however, is not just about Captain Vickers, but also of the other pilots, observers and airmen with whom he served with on 26 Reserve Squadron (RS), 58, 63, 11 (RS), 77, 36 and 101 Squadrons. It specifically details operations on 101 Squadron from its formation in July 1917 through to the end of May 1918 and the numerous sorties that Captain Vickers and some of his colleagues flew during that period.

Before Captain Vickers joined the RFC, he had served with the 11th Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment for seven months on the frontline in France. That in itself was not unusual, but the fact that he had been shot in the head while carrying out reconnaissance duties, surviving to later join the RFC, makes his story all the more remarkable.

It was only after extensive hospitalisation and rehabilitation that he made a full recovery and became fit enough to be transferred. After his flying training he continued to serve for another nine months through the winter of 191718, proving himself to be one of the RFCs most able and dedicated night-bomber pilots. Recognised by many of his contemporaries as being an exceptionally brave and intelligent officer, Captain Vickers was eventually credited with seventy-three sorties over enemy territory.

The need for air support was so demanding that Vickers often flew two sorties in a single night, although in early 1918, and on five separate occasions, he took part in three attacks in one night, during which he destroyed a vital bridge that was being strongly defended by the Germans. On 3 June 1918 he was named amongst the first officers to be awarded the DFC: a new medal instituted with the formation of the Royal Air Force. Captain Vickers was also awarded the MC, along with the 191415 Star, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal.

During the period of the First World War, airmen in the RFC often used language and jargon which added colour and humour to the dangerous business of flying. The cockpit of an aircraft was often referred to as the office; sorties as shows or stunts; enemy flak (anti-aircraft fire) was called Archie (from the music hall song of the time) or sometimes hate; and even in the official records the Germans were regularly referred to as Huns. Seemingly, such language was used to maintain morale and as a psychological tool to maintain animosity towards the enemy. For the most part I have tried to avoid using such terminology, except when quoting from original sources or where I have thought that it was necessary.

On a final note, I apologise for any inconsistencies in the spelling of the towns and villages that I have mentioned in the countries of France or Belgium. Depending on what record or log book you examine, many of them are spelt differently and indeed some of the places mentioned do not appear at all in modern-day maps. Some may have been no more than hamlets, while it is possible that others were many miles away from the place that is mentioned in the script.

![Bar Wing Commander Guy P. Gibson VC DSO - Enemy Coast Ahead [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/book/180257/thumbs/bar-wing-commander-guy-p-gibson-vc-dso-enemy.jpg)