First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword Aviation

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

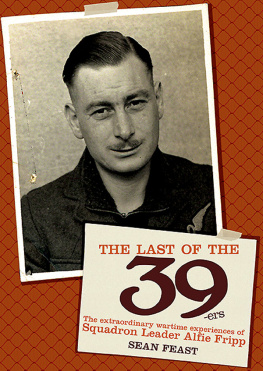

Copyright Sean Feast 2017

ISBN 978 1 47389 153 1

eISBN 978 1 47389 155 5

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47389 154 8

The right of Sean Feast to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword

Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family

History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways,

Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo

Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Acknowledgements

My thanks first and foremost go to John himself, a most distinguished gentleman. It has been an honour and a privilege to be able to tell his story and reminisce on a remarkable wartime career. Since being introduced by Ed Toop, we have spent a most enjoyable twelve months getting Johns adventures down on paper. Through the wonders of the world wide web, I found Pierre Michiels, a keen aviation enthusiast, who in turn introduced me to Ceanan Baird, son of the late Squadron Leader, The Honourable Robert Baird. Ceanan was extremely helpful in answering my questions and in very kindly allowing me sight of his fathers log book and photographs, some of which are reproduced in this book. Johns own log book was stolen, and so having access to another contemporary source was most helpful in piecing together Johns time in the Middle East. Other thanks go to: Tace Fox, archivist at Harrow School who provided information on Donald Crossley; Art Stacey, Treasurer/Membership Secretary of the Goldfish Club; and Sally Overthrow at the Ministry of Defence Medal Office. My work colleagues Alex, Imogen and Toto always deserve special mention for keeping me sane and allowing me the odd absence without question. Iona will be back soon! And finally to my genius wife Elaine, and two sons Matt and James who I hope never have to face the hardships that John and his contemporaries had to endure.

Chapter 1

The Waiting Game

John Brennan never had to go to war. He certainly didnt have to fight for the British. But somehow it just seemed like the right thing to do at the time.

The interview at the recruitment centre in Acton was the usual perfunctory affair. Hed arrived having sniffed the cold morning air on that January day in 1940 with his mind clear and his urge to do his duty apparent to anyone who might ask him to sign on the dotted line.

The desk sergeant showed no surprise at Johns Irish accent. But then why should he? Since the Famine there had been an Exodus of Irishmen to England, to escape starvation and seek salvation elsewhere. Hadnt the waterways and railways that criss-crossed the nation been built with the blood, sweat and cursing of the Irish Navvy? This was not the first, and certainly would not be the last Irishman to want to become a pilot.

The sergeant, John thought, was probably old enough to have been in the first show. The faded medal ribbon on his wingless breast pocket suggested that he had, and perhaps accounted for the warmth with which the young mans zeal to join His Majestys Royal Air Force was received.

Unusually, John was the only man in the queue and struck something of a forlorn figure. Not usually backward in coming forward, he hesitated slightly before daring to speak, at which point the sergeant looked up and smiled. John recalls:

Some will ask why I, as an Irishman, wanted to fight for the British when it was not my war. That is difficult to explain because whatever it was, it was felt by many thousands like me in the First World War and carried over into the second. It was our country.

I was the only one volunteering that day, or so it seemed. And I wanted to join the RAF. Id read in the national newspapers about the exciting trips that the heroic crews of the Wellingtons and Whitleys were flying over Germany, and that on occasion they had to fight off determined attacks from the German Luftwaffe. In the thick of the action were the air gunners, and despite never once having fired a shot in anger or even having held a gun or rifle, I was determined to become one of their number.

To Johns surprise, the RAF did not seem in a particular hurry to deploy his services. He was told he would have to be patient, and return at a later date when he would be up before an aircrew selection board to assess his suitability for operational flying. John was happy. He was in no particular rush himself. He had learned to be patient; learned to take disappointment and rejection. Hed worked hard to get where he was, and another few weeks was not going to make any difference. Besides, he had a girlfriend to keep him company that he hoped he would one day marry. So he could wait.

* * *

John Michael Brennan was born on 5 January 1921 in Ballylinan, a small, farming village in the parish of Castlecomer, County Kilkenny. His father had been in the 1st Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers and fought with the British Army in Gallipoli. His battalion suffered heavy casualties and was for a short time merged with another unit, the 1 Royal Munster Fusiliers to become The Dubsters. He was eventually evacuated in January 1916.

Returning to Ireland after the war, Johns father worked briefly in the local coalmines until the coming of the Irish Free State in 1922 when he joined the newly formed Irish Army and was posted to Callins Barracks, Cork, where he served until retirement. An intelligent and capable man, he was offered a commission but turned it down, preferring to stay among the ranks as a non-commissioned officer.

John lived with his parents at Evergreen Road (in the south of the City) for six years. The house was particularly small and the rooms sparse, with little by way of any mod cons or even furniture. There was a main room with a coal fire where they did the cooking and huddled for warmth, and a slightly larger room that was divided by curtains into bedrooms. There was nothing cosy about it; it was, in fact, thoroughly miserable.

Whereas some small boys can escape the misery of home and find refuge at school, for John there was no respite. The North Monastery School, to the north beyond the River Lee, was part of a much larger building and the windows were covered with a wire mesh that allowed layers of rubbish and detritus to congregate. It was a thoroughly depressing place, dank and dark, like something one would imagine in a Dickens novel rather than twentieth century Ireland. The head teacher was a priest, and the staff comprised both priests, monks and lay teachers.