CONTENTS

Guide

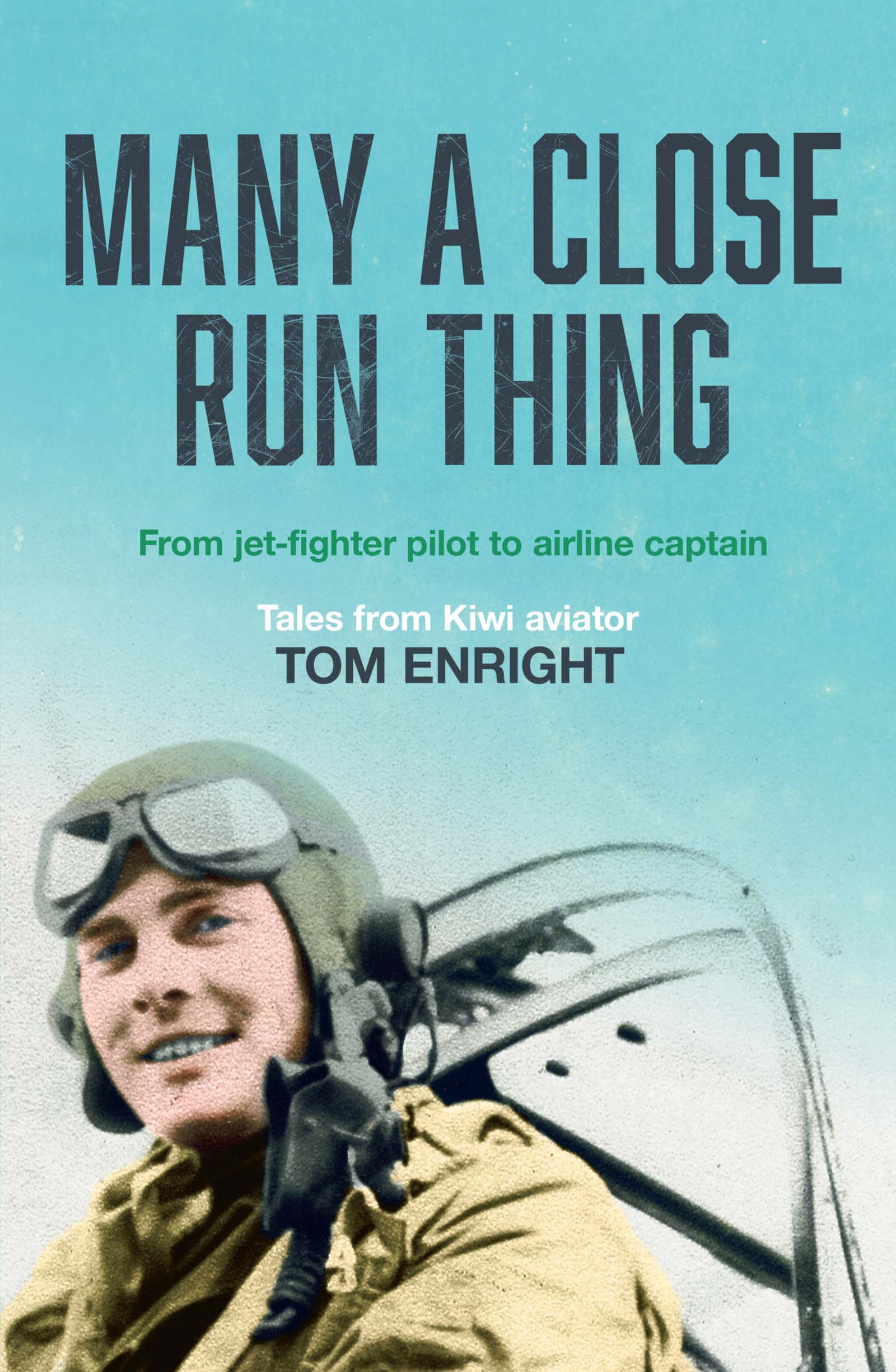

I began to write this book not long after tragically losing my dear wife, June. Just two days after the joyful celebration of the 50th anniversary of our marriage, she fell down stairs and died shortly thereafter. Left lamenting were five sons and their spouses, nine grandchildren and me. With sadness, we interred her ashes beneath a lacy Japanese maple in Aucklands beautiful Mt Eden Gardens.

I dedicate this book to my darling June.

And I am honoured to add also 14/75 and 5 Squadrons, RNZAF, and the wonderful staff and companions I met at the RAF College at Cranwell.

As between me and death, its been a close-run thing.

The Duke of Wellington, on his return from the Peninsular Wars

In military aviation, I had more than my fair share of close-run things.

Tom Enright

CONTENTS

A viation has given me a great life.

From my earliest days I have had an endless fascination with all things to do with flying. My enchantment began during my childhood in Central Otago, New Zealand. Horses were then in common use, few people owned motor cars and aeroplanes were a rarity. When a plane flew through our alpine skies, it was an event. People in nearby valleys would ring up cranking on the old party-line telephone to bring us the news that an aeroplane was headed our way. We children would rush outside and wait patiently until the mysterious buzzing object appeared in our patch of sky. The roar, muted by distance, of what seemed so powerful an engine was music to my ears. From my first distant encounter with an aeroplane I wanted to make flying my life.

Fast forward from the two room, one teacher school of St Bathans to secondary schooling in the City of Dunedin. There I joined the Air Training Corps of the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF). I overcame a terrifying first flight and soaked up everything to do with aviation which came my way. Schooling done, I joined the RNZAF as an engineering apprentice, choosing to study the trade of aircraft instruments. The RNZAF sent me to England at the age of 16. Leaving my parents and brothers and sisters behind was a wrench but there were many exciting things to look forward to.

On graduation, I was recommended for a cadetship with the Royal Air Force College at Cranwell, England (the RAF is the British air force) where I was awarded the coveted pilots wings.

My first 20 years flying was in a variety of military aircraft in which I had most interesting and thrilling experiences, including rather more than my fair share of close-run things. Then fortune smiled on me and I spent 25 years as an airline pilot.

When I talked about my experiences to people, both in and out of aviation, I was frequently exhorted to write about things which had happened to me. For a long time I remained diffident and perhaps a little shy about parading my life before the world. But gradually I have come to see that the lessons I have learned are of value to young people setting out on a flying career. I have also realised that interest in aviation and flying is quite widespread. I have enjoyed letting the memories spring onto paper. I hope there will be pleasure and interest in my words.

M y first flight was in a Tiger Moth. It was so terrifying that it is a wonder I ever flew again. But I overcame that experience and enjoyed 45 years of enthralling life in the air.

I was born into a farming family at Ranfurly, Otago Central, New Zealand in 1934 one of nine children and spent my early life in the district of St Bathans.

St Bathans is a famed gold mining district. The precious metal was discovered there in 1862. The lure of easy money attracted the usual horde of pick and shovel wielding fortune hunters but the primitive methods used by these rough men were not very productive. However, St Bathans was fortunate to attract the attentions of an enterprising Scotsman, one John Ewing. Of limited formal education, John had an active brain and excellent organisational abilities. He introduced to the New Zealand goldfields new methods from California which required large quantities of water to sluice away topsoil and uncover the gold. The water from rivers and streams plunging through the ancient hills was brought to the mines via hundreds of kilometres of water races. Building the races through rocky mountains and hills required herculean efforts. Surveyed with homemade equipment, they were laboriously hacked out with hand tools. Even vertical faces on some hills did not deter these resourceful men. They built up rock walls lying against the faces to the level required to transport the water across the face.

There were two major goldfields in this district: the Blue Lake and the Grey Lake. Each contained quantities of gold in deep folds in the earth. The Blue Lake started out as a large hillock but the miners sluiced it all away and managed to excavate the rich gravels and quartz beds to deep levels. Now filled with water, the ancient excavation has flooded to form a picturesque lake, which attracts tourists, swimmers and boaties from far afield.

My grandfather, an Irishman, had come to New Zealand with the initial rush of miners in the 1880s and arrived in St Bathans. He had the wisdom to recognise that the fifty thousand odd miners working in the district needed to be supplied with food and he became a farmer. He was also a successful gold miner and company director. My father, second youngest of six healthy children, ran one of Grandfathers operations, a coal mine. This thriving business supplied the village and surrounding areas. As a young man, my father had lots of gumption and go, riding to the hares and hounds, enlisting as a reservist in the New Zealand Territorial Army and attending annual army camps.

In 1914, my uncle Jack, the St Bathans postmaster, was first in the district to receive the news that Great Britain had accepted the New Zealand Governments offer of a fighting force to oppose the Germans. He immediately informed my father, who promptly volunteered. Dad was the first man in Central Otago to volunteer for active service in the army on the outbreak of World War I. As a country man with his own mounts, he was welcomed into the First Otago Mounted Rifles.

His War Service Certificate, which graces my office, records four years and 123 days war service, of which three years and 358 days were spent overseas. The theatres in which he served were Egypt (as part of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force), the Balkans and Western Europe. In Europe he was a trench mortarman, specialising in short range attacks on enemy trenches. His unit was popular as their mortar shells could shred the rolls of razor-sharp wire the Germans put up as barriers. On several occasions, he was loaned to the British army to assist in getting their wagons through the mud. He was gassed and shot in the foot and spent at least two periods in hospital.

We know that he had been wounded in Gallipoli and was sent to an English hospital. On discharge on sick leave, before rejoining his battalion, he visited County Wicklow, Ireland, his mothers birthplace. At a remote spot in the Irish countryside, his stagecoach driver said, This is as far as we go. Walk 25 miles that way. That distance being no problem to a fit young soldier he was soon knocking on the relatives door. Consternation! This was 1916 and Ireland was in rebellion. Runners were immediately despatched around the district to warn the more hot-headed republican sympathisers that this was not a British soldier and was to be left unharmed.

Next page

![Bar Wing Commander Guy P. Gibson VC DSO - Enemy Coast Ahead [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/book/180257/thumbs/bar-wing-commander-guy-p-gibson-vc-dso-enemy.jpg)