The surrender of Singapore was a catastrophic loss for the Allies in the Second World War. New Zealands very first air force fighter squadron, 488 Squadron of the RNZAF, was posted to Singapore just three months before it fell. This dynamic bunch of Kiwi fighters helped delay the enemys advance as best they could with severely limited resources and a good measure of Kiwi ingenuity. But the cost was high, and many would never discuss their experiences, never completely recover from that traumatic time.

Now, the son of one of those servicemen tells of his fathers war of 488 Squadron. Drawing on diaries, letters and photos, many never before made public, Last Stand in Singapore documents a relatively unknown story from New Zealands military history.

This narrative is dedicated to a group of young New Zealand men that volunteered to serve their country in its time of need.

They came from all walks of life and backgrounds for a common purpose to stop the invaders from the east.

Some died in that cause and many, many more suffered in mind and body for the rest of their lives.

Their story needs to be told.

Contents

- 1 To Singapore the journey begins

488 Squadron travels to its new posting - 2 An introduction to the East

New experiences, sights and sounds - 3 The struggle to become operational

Bad aircraft, no spares, limited training - 4 The arrival of the storm

The Japanese invasion - 5 The beginning of the end

A defensive collapse too little, too late - 6 The end draws near

Obliteration of the airfields and aircraft, evacuating to Sumatra - 7 Flight from the storm

An ignominious departure, evacuation on the Empire Star and escape from the Japanese - 8 In the eye of the storm

Arrival in Batavia and setting up for a second line of defence - 9 Of those that were left behind

The final stand six brave men POWs in Java - 10 Into calmer waters

Escape again, reaching the relative safety of Australia - 11 Safe but still far from home

A journey across the outback - 12 The aftermath

Questions needing answers

Of all the characters that figure in any narrative, there is always one who will stand out because of his or her personality. 488 Squadron had such a character. His name was John R Hutcheson, born in Wellington, New Zealand. He was posted to 488 Squadron as a flight lieutenant after early war service with the RAF in the United Kingdom. Known to all and sundry as Hutch, he personified the typical Kiwi attributes of that time: bravery and a stoical outlook on life. His attitude was to give it a go. He suffered hardship with humour and this endeared him not only to his commanding officer but to fellow 488 Squadron aircrew members and the groundcrew that served with him. He was to become a Flight Commander of B Flight of 488 Squadron during the Singapore and Batavia campaigns.

Hutchs nephew, Mike Hutcheson, kindly gave the author access to the diary notes and flying logbook that Hutch compiled during his time in the Far East, and the content of these notes figures significantly throughout the following narrative. I thought it fitting that the introduction that Hutch wrote all those years ago be printed here as a posthumous preamble to this narrative, as a tribute to his contribution to the defence of New Zealand at a critical time in our history. He survived the war after being shot down on many occasions before finally crash-landing in the jungle of Sumatra. He suffered continuing bouts of malaria in later years as a result of those experiences but died peacefully at home in 1984. He is remembered fondly by the surviving members of his squadron. For many years after the war his printing business in Tory Street, Wellington became a focal point for many of the ex-488 Squadron. In his own words:

Many people to whom I have spoken have laid the blame for the loss of Malaya and the Netherlands East Indies on Britain. This is not just. To obtain a reasonable perspective of the Malayan Campaign one must realise that Great Britain had been through Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain, and a heavy reverse in the Middle East. All the equipment and men that had been lost had to be made good. At this time, the amount of Lend Lease aid that was being made available to Britain was of no account. Much of the equipment received by Britain was obsolete and only accepted to keep faith with the Americanmanufacturersafter the fall of France, which had placed the original contracts. I myself saw cases and cases of American aircraft that were destined to remain crated. They were of no operational use, for their day was already past. Therefore Britain herself had to supply all the needed equipment, or a very big proportion of it. She had to rearm herself against a possible German attack and to re-equip the Middle East forces.

The inimitable Flight Lieutenant John Hutcheson Hutch whose spirit said it all, seated in his Brewster Buffalo fighter aircraft at Kallang, Singapore in late November 1941.

Ministry of Information, Singapore

Imagine how badly off we would now be had we lost the Middle East instead of Malaya. Possibly had we diverted sufficient equipment to Malaya to hold it, the Japanese would not have attacked, which would mean that the entry of America, at that stage anyway, would have been very problematical. To make Singapore strong enough to make it obvious to the Japanese that it would be a very tough nut would have required that equipment and men intended for the Middle East should be diverted with a consequent weakening of Egypt and the whole Middle East. Remember also that war was very real in the Middle East but only a threat so far as the Far East was concerned. There was alwaysthechance that it might be avoided. Sir Robert Brooke-Popham has often been criticised because he said that Singapore could withstand any assault. What else could he say? Come and attack us, Japan? We could only offer feeble resistance. Certainly it was a bluff, but he had no choice.

Still, this is not a political argument. It is the story of Singapore as I, a fighter pilot, saw it. Certainly there was much that could be criticised, and many who did not do what they should have done, or did it badly. Generally, though, there is good reason to doubt that even if everyone had done their very best possible we could have held out much longer.

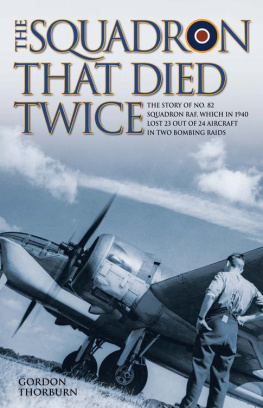

This is mainly the story of No. 488 (NZ) Fighter Squadron, a squadron with no experience and little training which was called upon to face up to odds greater than could reasonably have been expected. None of the pilots, with the exception of the commanding officer and his two flight commanders, had any experience of war. The rest of the pilots came straight from flying training schools in New Zealand, and against the standards of today had very few hours. Few if any of them had done more than twenty hours on Brewster Buffaloes at the outbreak of the Pacific War. Yet, in very inferior aircraft and with practically no training, they stood up without complaint to the best the Japanese could send.

Of the groundcrew personnel I cannot say enough. The social rules of the Far East debarred them from much of the society that they were accustomed to, for non-commissioned ranks rated equal with the native populace. They were not permitted to frequent the places that we commissioned officers could, and even we were not welcome. Before the war, to them (the local European population) service personnel were a dull and unnecessary bore.

![Haselden Mark - Buffaloes over Singapore: [RAF, RAAF, RNZAF and Dutch Brewster fighters in action over Malaya and the East Indies 1941-42]](/uploads/posts/book/212345/thumbs/haselden-mark-buffaloes-over-singapore-raf.jpg)