First published in 2019 by Huia Publishers

39 Pipitea Street, PO Box 12280

Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand

www.huia.co.nz

ISBN 978-1-77550-349-1 (print)

ISBN 978-1-77550-368-2 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-77550-368-2 (Kindle)

Copyright David B Hill 2019

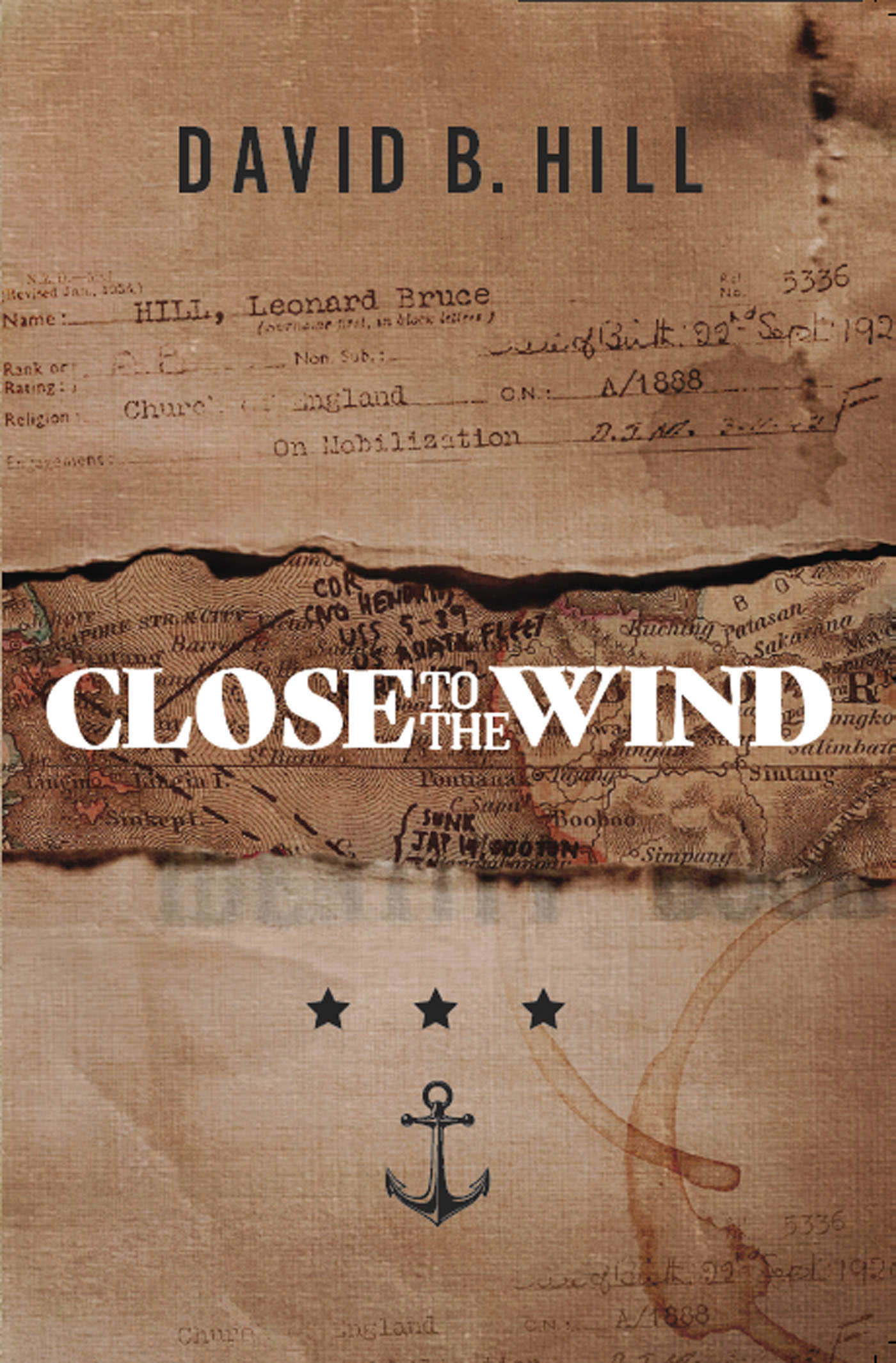

Cover images: Map of the East Indies Wikimedia Commons

Tea stain ArtsyBee / Pixabay.com

Anchor vector Yuri Chuprakov / Shutterstock

ML403 (on back cover above map) RNZN Museum

All other images David Hill

The haka Ka Mate, on pages 65, 66 and 189, was composed by Te Rauparaha, who was a chief of Ngti Toa Rangatira.

This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without the prior permission of the publisher.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

Published with the assistance of

Ebook conversion 2019 by meBooks

It is little known that among those New Zealanders who sailed off to war in 1940 was a group of 244 ratings from the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (New Zealand Division), many of them only teenaged.

Even less known is what happened to them.

Tama t, tama ora

Tama noho, tama mate.

He who stands lives.

He who sits perishes.

Contents

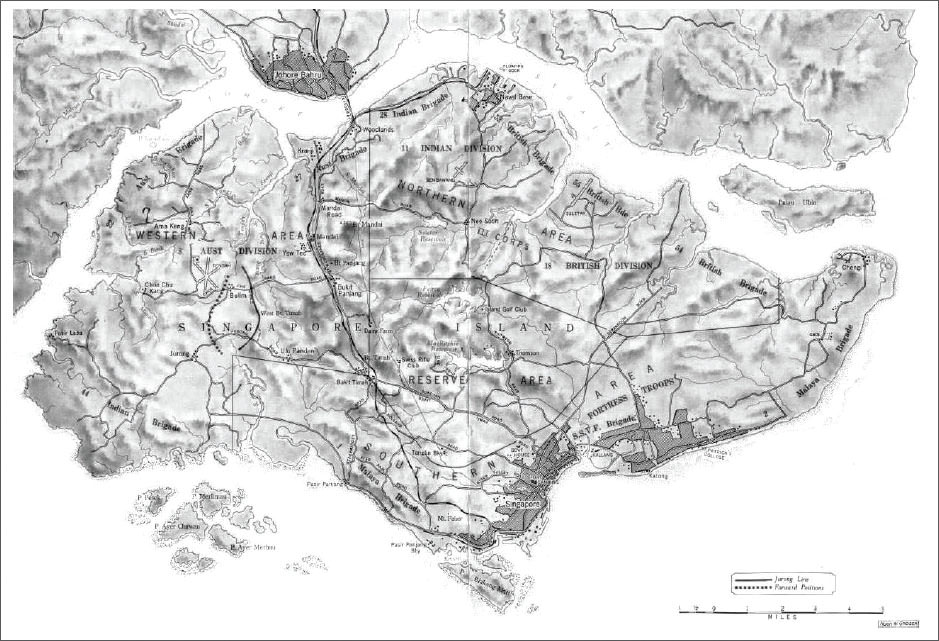

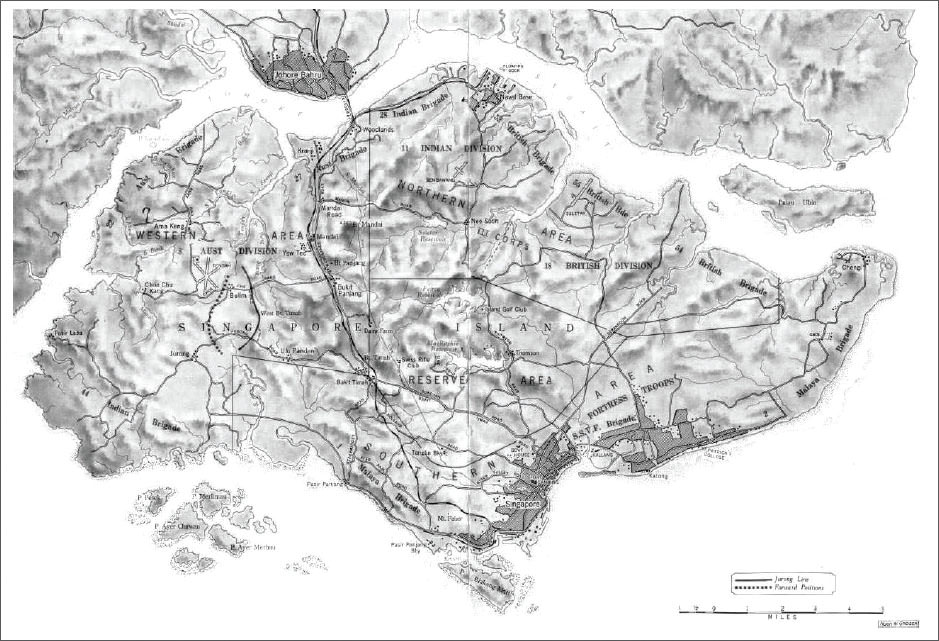

Wavell thought the Japanese would attack from the west; Percival thought they would attack the Naval Base. Wavell was right, and the poorly supported Australians bore the brunt.

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Because no part of Auckland is far from the sea, young Len Hill needed to travel only a couple of miles from his home in Mount Eden in order to reach it, which he did whenever he was able. He took the tram to Ponsonby, then walked down College Hill from Three Lamps and along past the Gas Company and Victoria Park to the edge of the harbour. He liked it best when the tide was out and he was able to walk it seemed for miles around the harbour edge, running his hands along the cliff face, tracing the serpentine geology of the shoreline. He explored beneath the contortions of massive phutukawa whose trunks hung impossibly from the cliffs above, or he wandered out along the mudflats between ramshackle wharves that had been allowed to stretch out into the bay, turning over stones and shells and odd bits of jetsam, looking for marine life. When the tide was full, he stood on the wharves and watched people fishing, and boatmen working the busy waterside of the old harbour, in air that offered the occasional rich mix of odours: salt, decomposing seaweed, fish in various stages of decay, paint and turpentine. A marine industry had built up along Beaumont Street, and Len would wander past the many boatyards, dawdling around the gates with curiosity, then make his way to the modest yacht clubs belonging to local communities, with names like Ponsonby, Victoria and Richmond, and watch the yachties work on their boats. Between the yacht clubs and the boatyards, beneath the cliff at Saint Marys Bay, stood a new, somewhat temporary-looking building next to a sliver of unused land left over after the reclamation of adjacent Freemans Bay. The building was more of a big shed built on stilts, standing in the water and accessible by a precarious staircase leading down the cliff face from the street above. The locals knew this stairway as Jacobs Ladder. To Len, as to most, the building below was a place distinguished only by some signage referring to the Navy.

He spent as much of his free time as he could messing around the shoreline, and he was rarely alone. The boys that hung around the Saint Marys Bay waterfront in the 1930s were an odd assortment. There was Jackie Hayward, and two brothers who both answered to the name of Mac. There were a couple of Grammar boys from Epsom, one with a perpetual smile whose name Len didnt know and the other a skinny, sandy-haired boy with whom Len connected the way small boys do, competing to skim stones the furthest distances, to climb higher up the cliff or out onto a phutukawa branch. Jack Hulbert was an only child who lived on Mountain Road in a big villa with a tennis court. He only looked undernourished. Jack had a yacht.

Len began to spend less time on the waterfront and more time on the water sailing in Jacks yacht, and, unsurprisingly, the friendship between the two prospered. Between them, they managed to raise twenty-five pounds and pay top price for a brand-new type of sailing dinghy called a Swift, marked with the conspicuous registration Z1.

Throughout the summers of the late 1930s, Jack and Len would take off into the outer Gulf, beyond Waiheke to Rakino and Ponui, sometimes for days. Or as long as the baked beans lasted. There was always somebody they knew out there somewhere, and they came across others they recognised often. It might be a day at Motukorea, picnicking on the beach, when some of the boys brought their girlfriends. Many times they were out overnight, rafted together in some bay. Practical lads, Len and Jack hoisted a canvas over the boom, which served very adequately as shelter. Occasionally they would sleep ashore: under the macrocarpas on Motutapu was a favourite choice. There they could lie on the soft forest floor, and the air was redolent with the aroma of pine. The breeze would hiss through the trees, and from the bay below came the sound of waves breaking. When they chose not to anchor in some rocky cove, they might raise the keel and let the boat settle on sand. If they didnt troll for kahawai, they would drop a line somewhere or winkle mussels from the rocks. The best of days were spent fishing at the Noises, or around Rakino, diving for scallops in the shallow waters then, as the sun went down, baking them open on corrugated iron over a fire.

They spotted shooting stars and named the constellations.

And they sailed.

Even in the late thirties, the combustion engine was still, for many, a technology beyond reach. Sail was king on the Gulf, and the boys revelled in the freedom it gave them. There was nothing like the sound of an anchor chain being hauled over the gunwale. It didnt matter in what direction they headed as long as they tasted salt on their lips and felt the wind on their backs and the sun on their faces. There was nothing like hoisting the little headsail and sheeting everything in hard. Nothing quite matched the thrill of sailing close to the wind.

Len often sat at the bottom of Jacobs Ladder, curious about the building standing in the water of Saint Marys Bay, and watched boys sail in and out of the bay in a whaleboat that was apparently stored inside. One day in the early spring of 1939, he was sitting there watching when a tall bloke, whom he had seen frequently on the waterfront, walked straight up the beach and stood in front of him. Confronted by this person, who stood head and shoulders above him, Len was forced to squint, trying to get the tall boys measure. Big ears. With the bright sun radiating from behind his head, they glowed bright red.

Next page