T HE B OAT

W ALTER G IBSON

Contents

To my wife, Mary, my daughter, Ree, and my son, Colin Roy, but for whom this story would never have been told.

My thanks are due to MacDonald Daly, the writer, whose untiring efforts shaped my war experiences into their present form; and to David Emsley for his constructive criticism and unfailing encouragement.

My name is Gibson. Walter Gibson, formerly of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, with whose 2nd Battalion I served for seventeen years in India, China and Malaya.

This story, as I plan it, will be completed on 2 March 1952for that will be the tenth anniversary of the morning I climbed into the boat.

I write this chronicleof the days of horror which I and Doris Lim, the Chinese girl, endured together in the boatbecause from all over the world, during the last two years, have come letters demanding that I should do so.

Late in 1949 my story, in briefer form, was told in a British Sunday newspaper.

As a sequel it was published, though still more briefly, in nearly all the tongues of the world. It appeared in newspapers and magazines in Europe, the United States, China, Japan and South America.

Readers Digest translated it into French, German, Spanish, Dutch, Italian, Danish, Swedish and Japanese.

And from all those countries, in all those tongues, have come requests from people who want to know more.

It is given to few, thank God, to drift for a month beneath a pitiless blazing sun, across 1,000 miles of ocean with nothing but a few handfuls of food and a few mouthfuls of water to sustain them during that time.

It is given to fewer still to be the only white survivor of such an ordeal.

And never again, I pray, may it be given to one man, as it was to me, to be the only white survivor of 135 souls who, on that morning of 2 March 1942, looked to the boat for salvation.

Four days before, the 1,000-ton Dutch K.P.M. steamer Rooseboom, with a crew of Dutch officers and Javanese seamen, left the port of Padang in Sumatra. She was carrying more than 500 evacuees from Malaya, most of them British.

Singapore had fallen to the Japanese. The evacuees included soldiers of many ranks, officials, policemen, traders, miners, planters, women and children.

The Rooseboom was taking them, crowded in her cabins and on her decks, to Ceylon and safety. There it was hoped that the regiments broken in the Malaya debacle would be formed again.

At midnight on Sunday, 1 March, the Rooseboom was torpedoed halfway to Ceylon. She sank in a few minutes. Only one of her boats was launched and kept afloat.

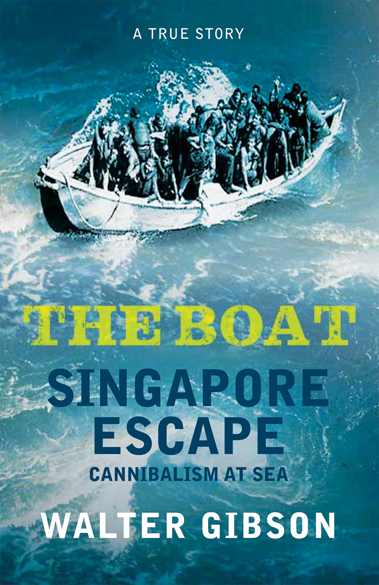

Towards it swam and paddled survivors. Eighty of them scrambled or were lifted into the boat. More than fifty others clung to the side.

The lifeboat was twenty-eight feet long and only eight feet at its widest part. The number of people it had been built to hold was twenty-eight.

For over a thousand miles, taking twenty-six days, she drifted across the Indian Ocean. Drama, tragedy, heroism, murder, pathos and self-sacrifice went with her day by day.

In the end, when the boat pounded on a coral island less than a hundred miles from the port of Padang from which the Rooseboom had sailed, only four people survived.

Two were Javanese sailors, whose final dreadful deeds aboard the boat made them unworthy of the life which was restored to them. The third was a Chinese girl, Doris Lim, who had worked for British Intelligence against the Japanese.

And I was the other.

I had fought with the Argylls, from last ditch to last ditch, in the bitter Malaya campaign of December 1941 and January 1942.

I had survived a six-week escape through the jungle after the Battle of Slim River.

I had crossed to Sumatra in a sampan and had joined up there with fellow Argylls and other troops before boarding the Rooseboom.

I had been asleep on a mattress on the Roosebooms deck when the torpedo struck.

But let me begin at the beginning

The docks and harbour of Padang, the Sumatran port, presented a grim sight in the days which immediately succeeded the fall of Singapore.

The town itself was crowded with people who had escaped from Malaya. The Japanese were bombing systematically.

The Rooseboom, usually engaged on the coastal run between Sumatra and Java, had been en route from Batavia to Ceylon and safety when she was ordered to pick up evacuees at Padang.

Now, deep down in the water from the human load she was carrying, she drew away from the quayside and we could see the half-submerged shipsvictims of the Jap raidwhich dotted the entrance to the harbour.

Even so, I found myself caught up in the spell of the sunsets beautyfor the dying rays fell on lush tropical vegetation on the dozens of islands about us. There are few more beautiful harbour approaches in the world than Padangs answer to Bremerhaven.

Behind me a voice said, Its lovely, Hoot, isnt it? and I turned to find Willie MacDonald by my elbow.

Sergeant Willie MacDonald was an old friend of mine. He had been wounded with the Argyll carrier platoon at Dipang, but had remained on duty until the battle was over. He had come out of hospital to join in the fighting on Singapore, and had escaped to Sumatra.

Aye, its lovely, Toorie, I answered him. The folks at home would give a bit to see this, wouldnt they?

Gie me Inverness, said Willie. And the Caledonian Canal.

It was a scrap of conversation I will never forgetthe words of a brave Highlander, many years away from home, but with his heart still in the silver city he was never to see again.

The atmosphere aboard the Rooseboom was a strange mixture of relief at leaving the perils of Malaya and Singapore behind, and of tension at the ever-present prospect of bombs and torpedoes.

A Jap plane had been over the port not long before we left, and we scanned the skies anxiously, our two Bren guns mounted.

The troops were packed like sardines and sleeping on deck almost on top of one another.

But after the Dutch captain had issued a bulletin that we were now out of bombing range, and two nights had passed without an event, tension lessened, everyone became more friendly and the atmosphere was very nearly carefree.

The senior army officer aboard the ship was Brigadier Archie Paris, who had commanded the division against hopeless odds during the Malayan campaign.

He and the brigade major, Major Angus MacDonald, member of a famous Argyllshire family and heir to a 200,000 estate, had escaped from Singapore in a yacht owned and sailed by a young officer of the Argylls, Captain Mike Blackwood.

Blackwood, red-haired and blue-eyed, was a tremendously keen yachtsman. He had won several races while we were stationed in Singapore before the campaign.

He, the brigadier and Major MacDonald were all engaged in the hand-to-hand fighting as Singapore fell.

At one stage about fifty Jap tanks threatened to penetrate into the rear of Singapore town. Mike Blackwood, with an anti-tank weapon and only one or two men, took up positions at the roadblock and engaged the leading tank at point-blank range.

He gained precious time for defenders back in the heart of Singapore.

The brigadier himself was known to those of us who had long service records in India as a fine soldier.

He was a powerfully built, handsome officer, his face deeply tanned from years of service, his iron-grey moustache always neatly clipped, his eyes shrewd and quizzical.

Always a great all-round athlete of exceptional strength, he took tremendous pride in his physical fitness, and on numerous occasions was able to outmarch men many years his junior.