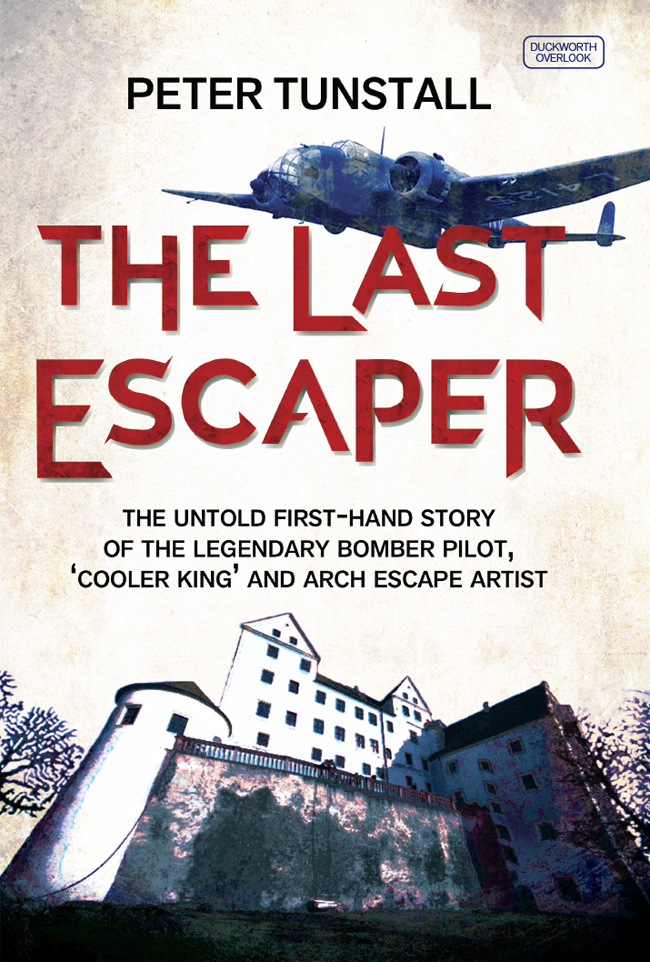

THE

LAST ESCAPER

Peter Tunstall, portrait by John Mansel

(see ).

THE

LAST ESCAPER

by

Peter Tunstall

DUCKWORTH OVERLOOK

This eBook edition 2014

First published in the UK and the US in 2014 by

Duckworth Overlook

LONDON

30 Calvin Street, London E1 6NW

T: 020 7490 7300

E:

www.ducknet.co.uk

For bulk and special sales please contact , or write to us at the above address.

NEW YORK

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales please contact , or write us at the above address.

2014 by Peter Tunstall

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

The right of Peter Tunstall to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available

from the Library of Congress

Published with assistance from the

Stickles Fund for Military History, Colgate University

ISBNs

UK: 978-0-7156-4923-7

Mobi: 978-0-7156-4970-1

ePub: 978-0-7156-4971-8

Library PDF: 978-0-7156-4972-5

Contents

Foreword

My great friend Dick Morganlater to be my best manand I succeeded in escaping from Spangenberg Castle, only to be recaptured a fortnight later and sent to Colditz after a term of solitary confinement. We were marched from Colditz railway station to the Schloss. My first view of this ancient castle was from the bridge over the river, and there it loomed above us. It was to house us for nearly two years. To my surprise I could hear the sound of cheering and pieces of material were being waved from the windowswhich, as we drew nearer, I could see were barred. The noise grew louder and by the time we entered the cobbled courtyard it had grown to pandemonium, sounding like a first-class riot.

The Germans had two tables in the yard, each placed against the wall below the windows, and German officers sat there to take our particulars, photograph us and so on. To my amazement, water bombs rained onto the tables, and then a blazing palliasse was thrown down out of an upper window. Grinning faces looked down, roaring insults at our captors. Eventually a riot squad doubled in, wearing coal-scuttle helmets and carrying weapons. The Germans pointed their rifles up at the prisoners above and the proceedings were then completed in comparative quiet. Until that time we had only seen the well-behaved officer prisoners at Westertimke, a naval officers camp near Bremen, and at Spangenberg. Clearly, morale at Colditz was terrific and the prisoners were men to be reckoned with and respected accordingly by their captors.

Eventually the German guards left and the inmates of Oflag IVC poured down into the courtyard. Im Jack Keats, said a smiling officer with glasses. Come and join our mess in the Belgian Quarters. Dick and I were taken up a spiral staircase with open doors off it through which we could see ablutions and lavatories, to a top floor and along it to an end room. This contained a number of double-tier bunks, plus some wooden tables and benches, and chairs made from Red Cross crates.

How do you do? I am Peter Tunstall. A well-built RAF officer with a moustache gave me a warm handshake. I learned that Peter Tunstall had just masterminded the near-riot that had only quietened down since the arrival of the armed German guards. Also that he was a fine shot with a water bomb and the result of his barrage on the tables on which the Germans had laid out the documents was chaotic and very effective.

Peter Tunstall obviously hated the Nazi system and he made this quite clear. When I got to know him better, he told me that before taking part in one of his first bombing raids, an official from the Air Ministry, who was lecturing him and his crew on how to behave if captured, told him that his first duty was to escape and his second was to be as big a bloody nuisance as possible. He was doing his best to achieve both and had already clocked up a record score of days in solitary confinement. Peter also told me that his Air Gunner, Sgt Joyce, an Irishman, was a cousin of William JoyceLord Haw-Hawwho was later executed for treason and whose body Sgt Joyce managed to get buried in Ireland after the war.

Peter Tunstalls book is an easy and interesting read, which certainly describes what it felt like to plan and actually carry out an escape; to be tired, hungry and thirsty in an enemy country, trying to avoid contact with the local population.

After the war Peter served in the Royal Air Force until 1958, and later settled in South Africa. A brave, charismatic and resourceful officer whose name will always be associated with Oflag IVC in Colditz Castle. This is his story.

Major-General Corran Purdon, C.B.E., M.C., C.P.M.

Introduction

Another escaping book? youre asking. Havent we done all that already? Surely by this time we know everything we need to know about British escapers in the Second World War. Indeed, hasnt it become a bit of a clich? With the theme to The Great Escape being played by fans at every England international football match; with the cardboard cut-out figures of the dashing POW and the dim-witted Hun having become, for the British, the nearest things to symbols of their respective nations; with the name Colditz instantly recognisablearent we in danger of stereotyping the Second World War, or even caricaturing it, as little more than a jolly good lark?

Well, yesand thats the point.

I too have read a great many of these escape stories. Some are classics of war literature and their accounts of life behind the wire ring very true to me. Others, to put it kindly, tell us more about the fantasy lives of their authors. But all of them, or nearly all, were written and published at a time very close to the events they describe. Their authors were still young men, with a young mans perspective on experiences still fresh and vivid in their minds. They were also producing their accounts at a moment when readers expected a certain kind of narrative about the war: one that played up the notion of the victory having been won because of the Allies (especially the British) superiority, rather than, as we now know, because of good fortune and the viciousness and short-sightedness of our enemies. Book-buyers werent interested in hearing about hunger, pain, loneliness or fear. They wanted tales of excitement and adventure, of derring-do and ultimate success. And that, by and large, is what they got. Its hardly surprising that escape books became a distinct genre. Nor is it accidental that the most famous onesPat Reids The Colditz Story, Eric Williams The Wooden Horse, Airey Neaves They Have Their Exitswere accounts of the rare break-outs in which the protagonists made it back to Britain, rather than the more typical ones where the would-be escapers were recaptured, or their attempts were foiled after months of difficult and dangerous work, sometimes before theyd even got outside the wire.

This book is different. There are three reasons why Ive written it. The first is that it is the very last of its kind that will ever appear. To the best of my knowledge, there are fewer than half a dozen of us still alive who were in Colditz during the Second World War. The book you hold in your hands is the final testimony that will ever be given by those who experienced these things for themselves.