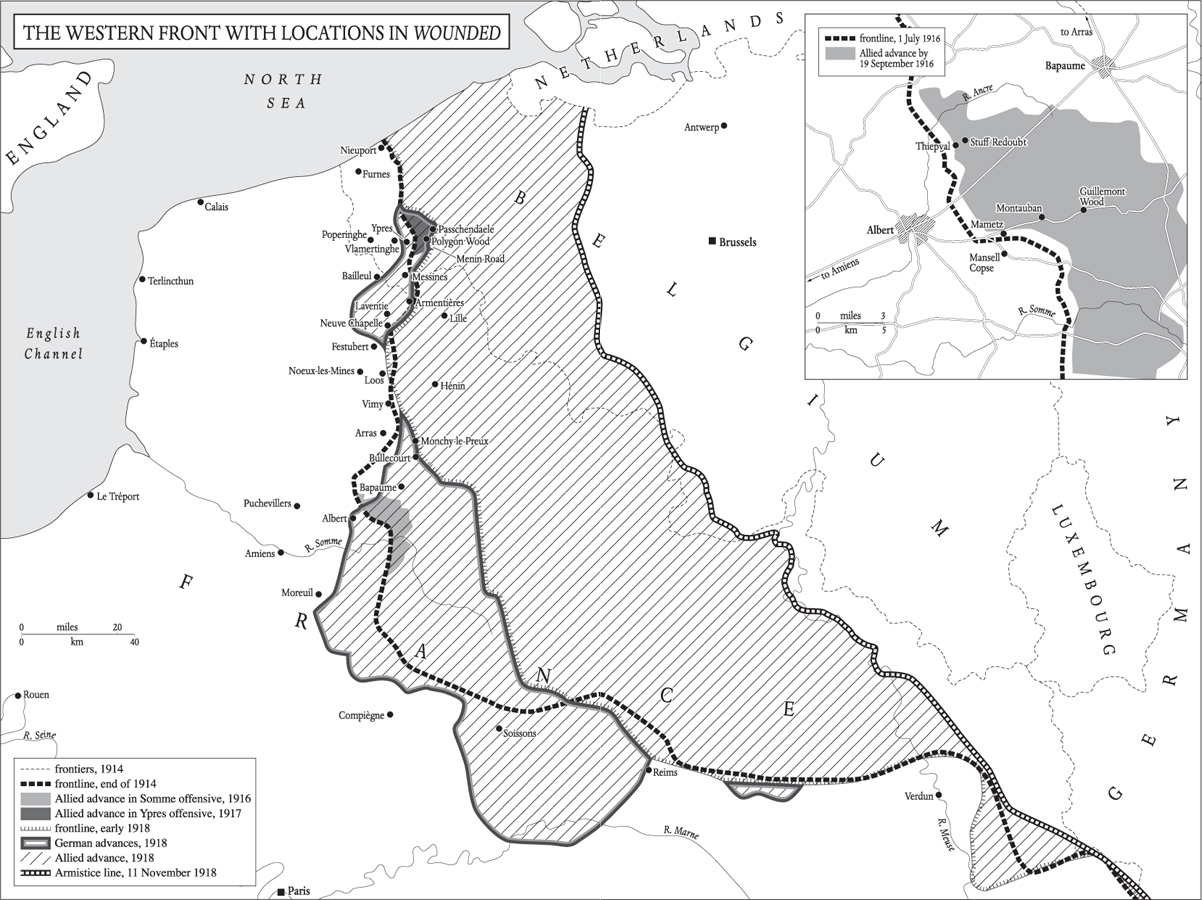

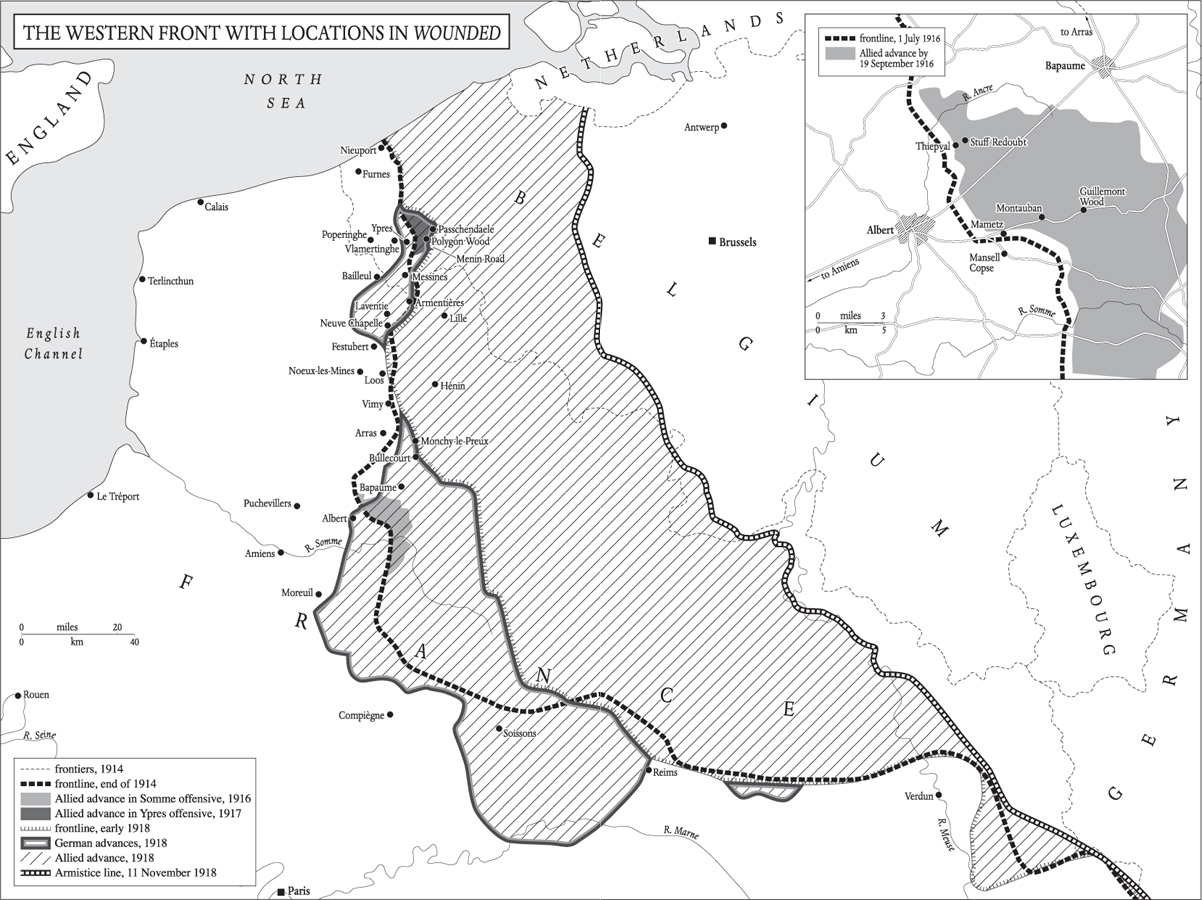

Wounded

Wounded

A New History of the Western Front in World War I

EMILY MAYHEW

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research,

scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Emily Mayhew 2014

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

The Bodley Head

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mayhew, E. R. (Emily R.)

Wounded : a new history of the Western Front in World War I / Emily Mayhew.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-19-932245-9

1. World War, 19141918Medical careGreat BritainCase studies.

2. World War, 19141918Medical careEurope, WesternCase studies.

3. Great Britain. ArmyMedical careHistory20th century.

4. Medicine, MilitaryGreat BritainHistory20th century. I. Title.

D629.G7M19 2013

940.47541dc23 2013016329

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

Contents

1

Wounded

Mickey Chater, Neuve Chapelle, 12 March 1915

2

Bearers

Earnest Douglas, William Young, William Easton

3

Regimental Medical Officers

John Linnell, William Kelsey Fry, Alfred Hardwick, Charles McKerrow

4

Surgeons

Henry Souttar, Norman Pritchard, John Hayward

5

Wounded

Bert Payne, Montauban, 1 July 1916

6

Nurses

Jentie Patterson, Winifred Kenyon, Elizabeth Boon

7

Orderlies

Alfred Arnold, Harold Foakes

8

Wounded

John Glubb, Menin Road, 21 August 1917

9

Chaplains

Wilfred Abbott, Ernest Crosse, Charles Doudney, John Murray, Cyril Horsley-Smith, Montagu Bere, John Lane Fox

10

Ambulance Trains

Nurse Bickmore, Nurse Morgan, Margaret Brander, Leonard Horner

11

Furnes Railway Station

Sarah MacNaughtan

12

Wounded

Joseph Pickard, Moreuil, Easter Sunday 1918

13

The London Ambulance Column

Claire Tisdall

Being wounded was one of the most common experiences of the Great War. On the Western Front, almost every other British soldier could expect to become a casualty, with physical injuries ranging in severity from light wounds to permanent, life-changing disabilities. Yet in the historical record of the First World War, the wounded and the men and women who cared for them are an undiscovered, somehow silenced group. As readers of Great War history, we have become accustomed to the noise of the blasting, thumping barrage and the shrieks of officers whistles ordering the men over the top. We are much less accustomed to the sounds of the voices of the wounded. The scale and power of the fighting has drowned them out. But their stories deserve to be heard and understood just as we have learned to listen to the words of the war poets for everything they can tell us about suffering and war.

Much of what we do know about the wounded of the First World War comes from writers of fiction. Bestselling books such as Birdsong and Regeneration tell beautiful and moving stories of casualties, nurses and doctors, and the extraordinary play War Horse is set at a medical aid post where Joey and Topthorn pull ambulances. These works are based on detailed historical research but they are not nor are they intended to be history. Wounded is about the real men and women who inspired these writers. It is a work of historical rediscovery but it is not a conventional history. Like a novel, it uses a continuous narrative to interweave the testimonies of injured soldiers and stretcher bearers, doctors and surgeons, nurses and chaplains, orderlies and hospital train staff, and volunteers in train stations in France and Britain. By bringing together all these different voices for the first time, the book guides the reader through the world of the wounded and those who cared for them.

Writing Wounded in this unconventional way was not simply a question of preference for one representational style over another. As I researched the book, I came to realise that the only choice I had as a historian was to tell the story unconventionally or not tell it at all. The conventional approach would require an analysis of the official archive of military medical operations during the Great War to create a comprehensive overview of the planning and process of medical care. Policy documents from the War Office would be meshed with implementation reports from the Army Medical Services. Treasury financial records would coordinate with Royal Army Medical Corps staffing reports. Hospital archives would align with casualty statistics. Finally, some personal testimony would be added to provide colour and human detail to the history of the huge operational undertaking. Yet such a conventional approach proved impossible, for one simple reason: very few of those documents are still available. Most of the material that was in the national archives relating to the medical conduct of the war is gone; what is left is at best partial. In the mid-1920s no one could think of a reason to keep the mass of official documents relating to such a relatively narrow aspect of the war, so no one did.

Thus the history had to be written with what was left, and it turned out that what was left was enough. I began to gather testimonies of individuals, most of them unpublished, and bring them together in a collective narrative. Some were tucked into a file in an archive, faded and almost forgotten; some were just a page or a fragment from a hastily scribbled letter home. Others were well-organised, neatly written accounts spanning the entire course of the war. There was the rough and unschooled voice of the stretcher bearer and the smooth, educated prose of the surgeons memoir. Nurses diaries told of the dreadful nights when they were almost overwhelmed by casualties coming to them straight from the Somme, but also of how they coped living so close to the war. Orderlies wrote of the unexpected moments of happiness they experienced moments that could confound them as much as the never-ending violence of the front. Some of the most valuable testimony came from a group without previous medical training or experience: the army chaplains who took on new and unexpected roles in hospitals, aid posts, and sometimes on the battlefield, as they tried to find ways of offering service in a place of suffering. Bringing all these voices together I began to assemble a history of the central experience that was repeated hundreds of thousands of times up and down the Western Front and went beyond rank or status: the wounding of a soldier and the struggle of medics to save his life.

Next page