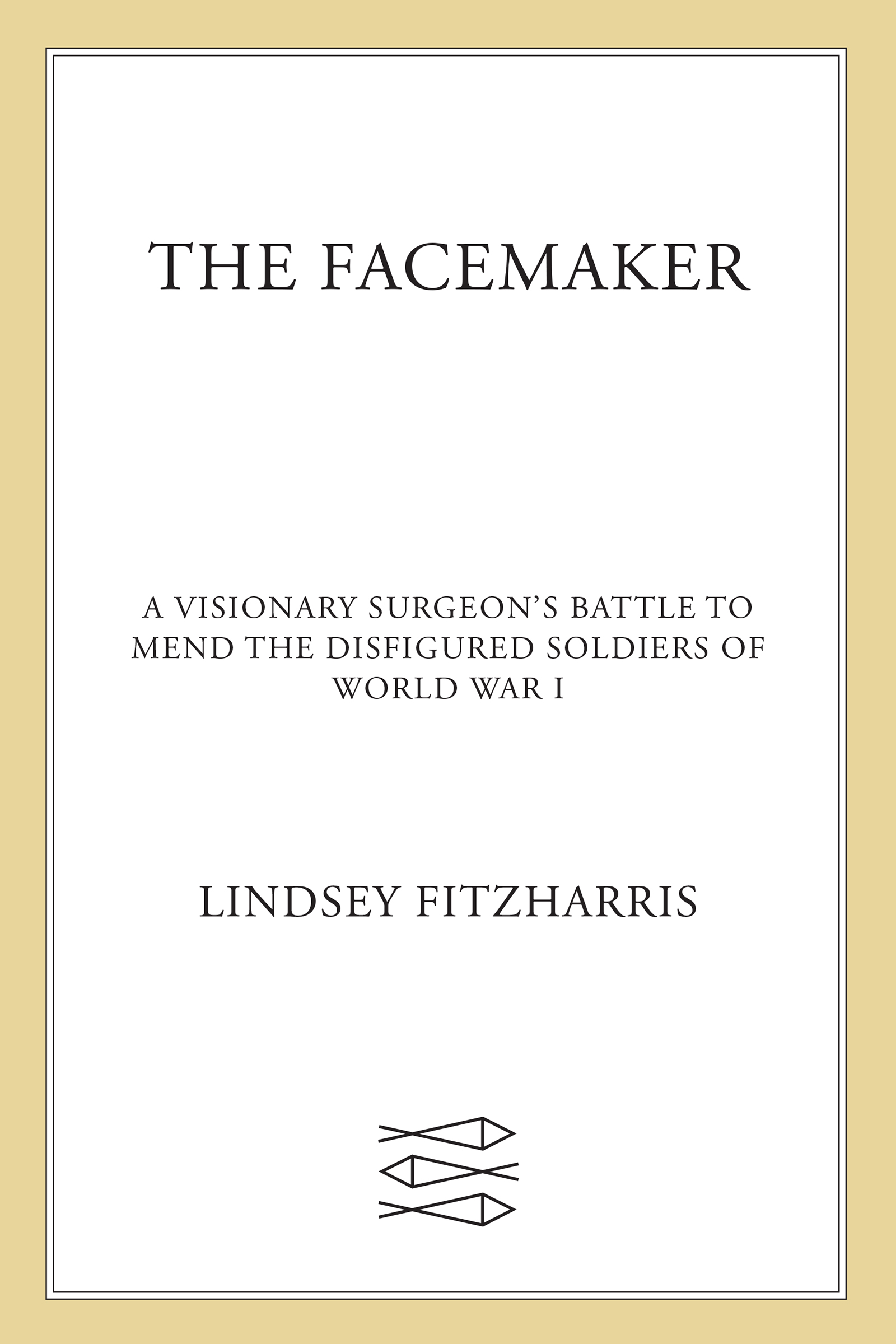

Lindsey Fitzharris - The Facemaker: A Visionary Surgeons Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I

Here you can read online Lindsey Fitzharris - The Facemaker: A Visionary Surgeons Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Facemaker: A Visionary Surgeons Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Facemaker: A Visionary Surgeons Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Facemaker: A Visionary Surgeons Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A New York Times Bestseller

Enthralling. Harrowing. Heartbreaking. And utterly redemptive. Lindsey Fitzharris hit this one out of the park. Erik Larson, author of The Splendid and the Vile

Lindsey Fitzharris, the award-winning author of The Butchering Art, presents the compelling, true story of a visionary surgeon who rebuilt the faces of the First World Wars injured heroes, and in the process ushered in the modern era of plastic surgery.

From the moment the first machine gun rang out over the Western Front, one thing was clear: humankinds military technology had wildly surpassed its medical capabilities. Bodies were battered, gouged, hacked, and gassed. The First World War claimed millions of lives and left millions more wounded and disfigured. In the midst of this brutality, however, there were also those who strove to alleviate suffering. The Facemaker tells the extraordinary story of such an individual: the pioneering plastic surgeon Harold Gillies, who dedicated himself to reconstructing the burned and broken faces of the injured soldiers under his care.

Gillies, a Cambridge-educated New Zealander, became interested in the nascent field of plastic surgery after encountering the human wreckage on the front. Returning to Britain, he established one of the worlds first hospitals dedicated entirely to facial reconstruction. There, Gillies assembled a unique group of practitioners whose task was to rebuild what had been torn apart, to re-create what had been destroyed. At a time when losing a limb made a soldier a hero, but losing a face made him a monster to a society largely intolerant of disfigurement, Gillies restored not just the faces of the wounded but also their spirits.

The Facemaker places Gilliess ingenious surgical innovations alongside the dramatic stories of soldiers whose lives were wrecked and repaired. The result is a vivid account of how medicine can be an art, and of what courage and imagination can accomplish in the presence of relentless horror.

Lindsey Fitzharris: author's other books

Who wrote The Facemaker: A Visionary Surgeons Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.