Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my grandma Dorothy Sissors, my bonus in life

When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is almost certainly wrong.

ARTHUR C. CLARKE

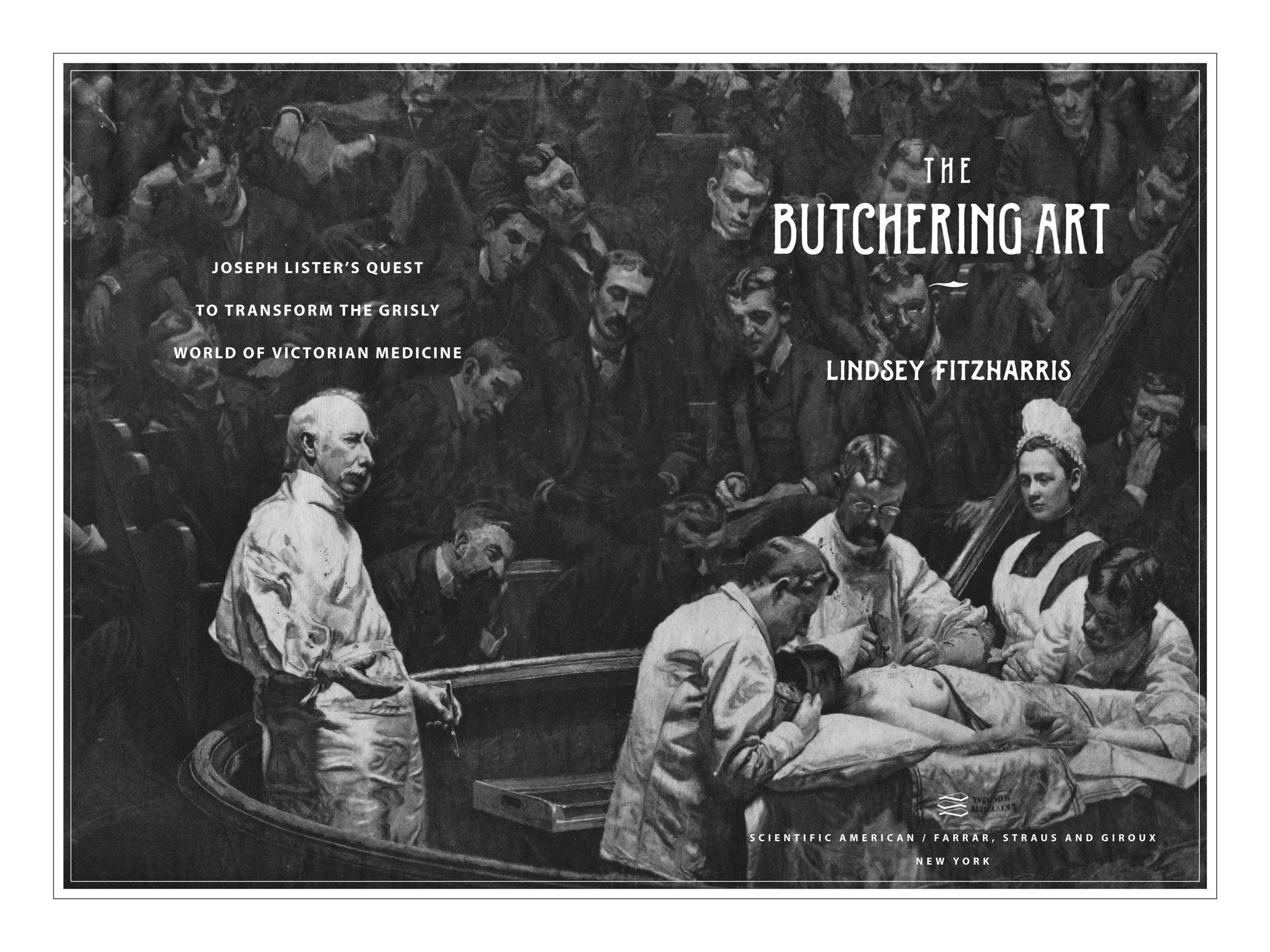

O N THE AFTERNOON OF DECEMBER 21, 1846, hundreds of men crowded into the operating theater at Londons University College Hospital, where the citys most renowned surgeon was preparing to enthrall them with a mid-thigh amputation. As the people filed in, they were entirely unaware that they were about to witness one of the most pivotal moments in the history of medicine.

The theater was filled to the rafters with medical students and curious spectators, many of whom had dragged in with them the dirt and grime of everyday life in Victorian London. The surgeon John Flint South remarked that the rush and scuffle to get a place in an operating theater was not unlike that for a seat in the pit or gallery of a playhouse. People were packed like herrings in a basket, with those in the back rows constantly jostling for a better view, shouting out Heads, heads whenever their line of sight was blocked. At times, the floor of a theater like this one could be so crowded that the surgeon couldnt operate until it had been partially cleared. Even though it was December, the atmosphere inside the theater was stifling, verging on unbearable. The crush of bodies made the place feel plaguey hot.

The audience was made up of an eclectic group of men, some of whom were neither medical professionals nor students. The first two rows of an operating theater were typically occupied by hospital dressers, a term that referred to those who accompanied surgeons on their rounds, carrying boxes of supplies needed to dress wounds. Behind the dressers stood the pupils, who restlessly pushed and murmured to one another in the back rows, as well as honored guests and other members of the public.

Medical voyeurism was nothing new. It arose in the dimly lit anatomical amphitheaters of the Renaissance, where, in front of transfixed spectators, the bodies of executed criminals were dissected as an additional punishment for their crimes. Ticketed spectators watched anatomists slice into the distended bellies of decomposing corpses, parts gushing forth not only human blood but also fetid pus. The lilting but incongruous notes of a flute sometimes accompanied the macabre demonstration. Public dissections were theatrical performances, a form of entertainment as popular as cockfighting or bearbaiting. Not everyone had the stomach for it, though. The French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau said of the experience, What a terrible sight an anatomy theatre is! Stinking corpses, livid running flesh, blood, repellent intestines, horrible skeletons, pestilential vapors! Believe me, this is not the place where [I] will go looking for amusement.

The operating theater at University College Hospital looked more or less the same as others in the city. It consisted of a stage partially enclosed by semicircular stands rising one above another toward a large skylight that illuminated the area below. On days when swollen clouds blotted out the sun, thick candles lit the scene. In the middle of the room was a wooden table stained with the telltale signs of past butcheries. Underneath it, the floor was strewn with sawdust to soak up the blood that would shortly issue from the severed limb. On most days, the screams of those struggling under the knife mingled discordantly with everyday noises drifting in from the street below: children laughing, people chatting, carriages rumbling by.

In the 1840s, operative surgery was a filthy business fraught with hidden dangers. It was to be avoided at all costs. Due to the risks, many surgeons refused to operate altogether, choosing instead to limit their scope to the treatment of external ailments like skin conditions and superficial wounds. Invasive procedures were few and far between, which was one of the reasons why so many spectators flocked to the operating theater on the day of a procedure. In 1840, for instance, only 120 operations were performed at Glasgows Royal Infirmary. Surgery was always a last resort and only done in matters of life and death.

The physician Thomas Percival advised surgeons to change their aprons and to clean the table and instruments between procedures, not for hygienic purposes, but to avoid every thing that may incite terror. Few heeded his advice. The surgeon, wearing a blood-encrusted apron, rarely washed his hands or his instruments and carried with him into the theater the unmistakable smell of rotting flesh, which those in the profession cheerfully referred to as good old hospital stink.

At a time when surgeons believed pus was a natural part of the healing process rather than a sinister sign of sepsis, most deaths were due to postoperative infections. Operating theaters were gateways to death. It was safer to have an operation at home than in a hospital, where mortality rates were three to five times higher than they were in domestic settings. As late as 1863, Florence Nightingale declared, The actual mortality in hospitals, especially in those of large crowded cities, is very much higher than any calculation founded on the mortality of the same class of diseases amongst patients treated out of the hospital would lead us to expect. Being treated at home, however, was expensive.

The infections and the filth werent the only problems. Surgery was painful. For centuries, people sought ways to make it less so. Although nitrous oxide had been recognized as a painkiller since the chemist Joseph Priestley first synthesized it in 1772, laughing gas was not normally used in surgery, because its results were unreliable. Mesmerismnamed after the German physician Franz Anton Mesmer, who invented the hypnotic technique in the 1770shad also failed to be accepted into mainstream medical practice in the eighteenth century. Mesmer and his followers thought that when they moved their hands in front of patients, a physical influence of some kind was generated over them. This influence created positive physiological changes that would help patients heal and could also imbue a person with psychic powers. Most doctors remained unconvinced.

Mesmerism enjoyed a brief revival in Britain in the 1830s, when the physician John Elliotson began holding public displays at University College Hospital during which two of his patients, Elizabeth and Jane OKey, were able to predict the fate of other hospital patients. Under Elliotsons hypnotic influence, they claimed to see Big Jacky (otherwise known as Death) hovering over the beds of those who later died. Any serious interest in Elliotsons methods was short-lived, however. In 1838, the editor of The Lancet , the worlds leading medical journal, tricked the OKey sisters into confessing their fraud, thus exposing Elliotson as a charlatan.

The scandal was still fresh in the minds of those attending University College Hospital on the afternoon of December 21, when the renowned surgeon Robert Liston announced hed be testing the efficacy of ether on his patient. We are going to try a Yankee dodge today, gentlemen, for making men insensible! he declared as he made his way to the center of the stage. A hush fell over the theater as he began to speak. Like mesmerism, the use of ether was seen as a suspect foreign technique for putting people into a subdued state of consciousness. It was referred to as the Yankee dodge due to its being first used as a general anesthetic in America. It had been discovered in 1275, but its stupefying effects werent synthesized until 1540, when the German botanist and chemist Valerius Cordus created a revolutionary formula that involved adding sulfuric acid to ethyl alcohol. His contemporary Paracelsus experimented with ether on chickens, noting that when the birds drank the liquid, they would undergo prolonged sleep and awake unharmed. He concluded that the substance quiets all suffering without any harm and relieves all pain, and quenches all fevers, and prevents complications in all disease. Yet it would be several hundred years before it was tested on humans.