GREAT DISCOVERIES IN SCIENCE

The Germ Theory of Disease

Kristin Thiel

Published in 2018 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2018 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016.

Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #CS17CSQ

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Thiel, Kristin, 1977

Title: The germ theory of disease / Kristin Thiel.

Description: New York : Cavendish Square Publishing, [2018] | Series: Great discoveries in science | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016058597 (print) | LCCN 2016059923 (ebook) | ISBN 9781502627742 (library bound) | ISBN 9781502627759 (E-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Germ theory of disease. | Diseases--Causes and theories of causation.

Classification: LCC RB153 .T45 2018 (print) | LCC RB153 (ebook) | DDC 616--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016058597

Editorial Director: David McNamara

Editor: Caitlyn Miller

Copy Editor: Michele Suchomel-Casey

Associate Art Director: Amy Greenan

Designer: Lindsey Auten

Production Coordinator: Karol Szymczuk

Photo Research: J8 Media

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of: Cover, De Wood, Pooley, USDA, ARS, EMU/File: ARS Campylobacter jejuni.jpg/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain; p. w: Florence Nightingale(18201910)/File: Nightingale-mortality.jpg/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain.

Printed in the United States of America

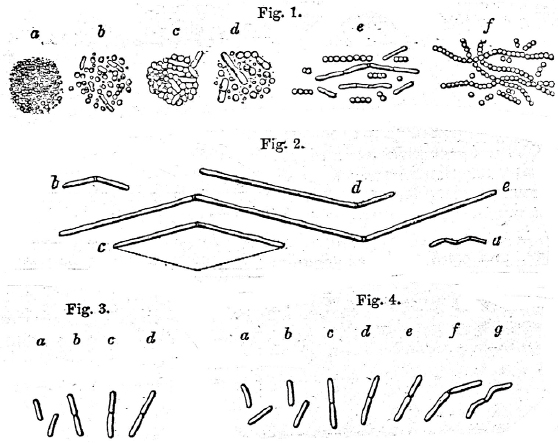

This visual explanation of germ theory is from an 1868 lecture given at the Royal College of Surgeons.

THE GERM THEORY OF DISEASE

Introduction: Invisible and Deadly Germs

I ts possible you have a piece of germ theory history in your medicine cabinet, in the bottle of green or blue liquid next to the toothpaste: mouthwash. Mouthwash was an early result of the discovery and understanding of germs. Its inventor was Joseph Lister, a British surgeon in the 1800s whose advancements in science helped usher in germ theory as the prevailing wisdom about disease that we still hold today.

Soap, your chore of taking out the garbage, the shots you get at the doctors office before the school year startsthese are all the results of germ theory, which states that germs can make us sick and offers precautions we can take to block the germs from reaching us, kill them, or make them behave in milder ways. More than that, this relatively new knowledge entirely changed the way humans see the world.

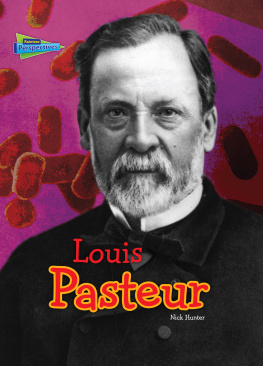

Before the work of Listerand researchers, scientists, and medical professionals like Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch, Ignaz Semmelweis, and John Snow, among many otherswe had no idea that a whole other world of living, eating, reproducing, and working microorganisms existed alongside ours. Before the invention of the microscope, which allowed us to see germs and other microorganisms, we could not prove definitively that they existed. New questions, also, had to be presented and investigated. Its easy to hold on to old ideas and beliefs, so it took time for the space to be created in which people could wonder and accept new possibilities.

Face masks act as a barrier to germs.

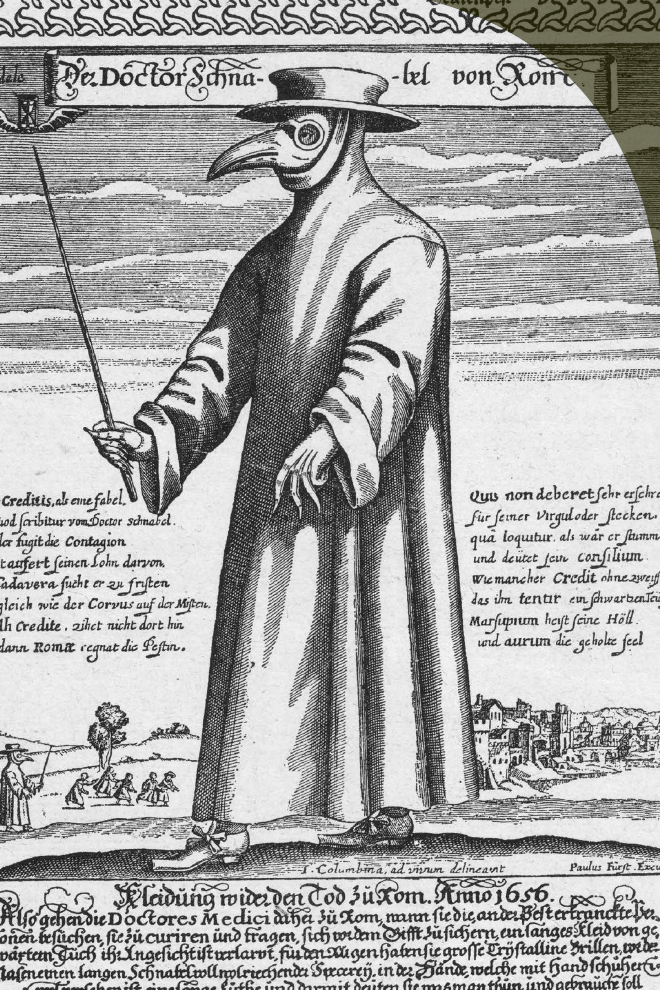

For most of human history, people believed in otherworldly reasons for illness. Supernatural beings like gods, demons, and spirits were thought to curse or punish humans with sickness, or, in a long-standing scientific theory, it was thought that bad air caused disease. In the minds of early scientists, rotten smells were indicators that a miasma was present: unhealthy air, which might have drifted over to us from a marsh, from decaying plant or animal matter, or even from deep within Earth, disturbed by an earthquake, or from high above the world and agitated by extreme celestial movement. Today, people particularly vulnerable to disease may wear nose-and-mouth masks when they go out in public, but thats to protect them from the germs carried by the air, not the air itself, which people used to fear.

And tomorrow, we may see germs in yet another whole new light. Investigators are increasingly convinced that some diseases we assumed were hereditary or environmental have connections to bacteria or viruses. If they do, we may be able to prevent or treat previously unstoppable illnesses with medication or dietary changes that kill the germs. A growing body of data also shows that there are concrete actions we can take, like improving access to clean water, to force germs to evolve to be milder. We can also use our always changing computer technology, as the people of yesterday did with the groundbreaking microscope, to better report and track infectious and contagious diseases, thereby helping people get healthy and stay well. Yet no matter what the future holds, germ theory will play a big role in how humans interact with the world.

In this mid-1600s illustration, a doctor protects himself from disease with a mask of air-purifying spices.

CHAPTER 1

The Problem of Disease

U ntil the nineteenth century, people did not know about the existence of germsso, until then, they also didnt know what caused diseases, how they spread from person to person, and how to cure or prevent them. That didnt mean people werent curious to understand or, especially when epidemics like the plague killed thousands, desperate to be able to prevent the spread and cure those who were ailing. Disease in the form of unhealthy air and spontaneous generation of disease were two theories people held for many years.

The PROBLEM with AIR

The idea of bad air, corrupted air, pestilential air, putrefied air, or miasmathere have been many descriptions over the centuriesis one of humanitys longest-running theories. At least as far back as ancient Greece and through to the mid-1800s, people thought that unpleasant smells caused disease or even were disease. The name of one illness, which continues to put almost half the worlds population at risk, reminds us of this history: the word malaria is from the Italian mal aria, bad air.

The miasma theory was fine-tuned with each new and more aggressive disease. Europes Middle Ageswhich began with the fall of Rome in 476 CE (also known as the fifth century) and ended with the Renaissance, starting in the mid-1300s (the fourteenth century)is considered miasma theorys heyday. As communities became denser in population, there were more ferocious diseases than there ever had been. For example, Europes first bubonic plague killed fifty million people, or 60 percent of Europes population, in the seven-year span of 1346 to 1353. Syphilis came to Europe via sailors returning from world explorations and spread during wars between European countries. In 1519, across the Atlantic Ocean, Hernando Corts and his Spanish army invaded Mexico, which had a population of twenty-two million. By the turn of the century, only two million remained, due to the devastation wrought by European smallpox and New World

Next page