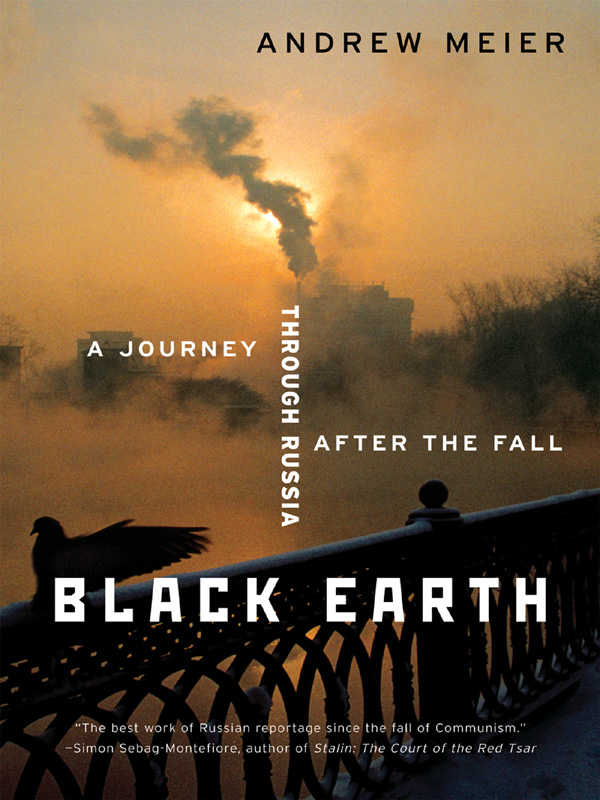

BLACK EARTH

A JOURNEY THROUGH RUSSIA

AFTER THE FALL

ANDREW MEIER

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint lines from: Black Earth, from Osip Mandelstam, Selected Poems , Penguin Books, published 1991 and translated by James Greene (by kind permission of Angel Books, London); Hadji Murad , in Leo Tolstoy, Master and Man and Other Stories , Penguin Classics, 1977, translated by Paul Foote; Gubernatorskie romansy , Moskovskii pisatel, 1994, by Valentin Fyodorov. Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of all translated material. Rights holders of any material not credited should contact W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110.

Copyright 2003 by Andrew Meier

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First published as a Norton paperback 2005

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Manufacturing by The Haddon Craftsmen, Inc.

Book design by Blue Shoe Studio

Production manager: Julia Druskin

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Meier, Andrew.

Black earth : a journey through Russia after the fall / by Andrew Meier.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-393-05178-1 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-393-24206-5 (e-book)

1. Russia (Federation)Description and travel. 2. Meier, AndrewJourneysRussia (Federation) 3. Russia (Federation)Social conditions1991 4. Post-communismRussia (Federation) I. Title.

DK510. 76.M44 2003

914. 70486dc21

2003006562

ISBN 0-393-32641-1 pbk.

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

for Mia,

and for my parents

How pleasing fatty topsoil is to ploughshare,

How silent the steppe in its April upheaval!

Well, I wish you well, black earth: be firm, sharp-eyed

A black-voiced silence is at work.

Osip Mandelstam, Black Earth, April 1935

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

AUTHORS NOTE

One can transliterate the Russian language into Latin script variously. I have elected not to use the American scholarly standard, the Library of Congress system, in the hope of rendering the Russian as readable and recognizable as possible. (As such, the reader will find Yeltsin and not Eltsin.) With regard to translations, I have sought to use existing English texts whenever possible. Only when such translations do not exist or fall short of the Russian have I resorted to my own. Lastly, in a few rare cases, to protect the safety of individuals I have substituted names.

HE HAD BEEN THEIR FIRST CHILD, the elder of two sons. After his death they had turned the darkest corner of the spartan living room into a shrine. A hazy black-and-white portrait, blown up beyond scale from an army ID, loomed above the reedy church candles and a thin bouquet of plastic flowers. They had draped a black ribbon over the photograph.

When I served, his father said, I served the Motherland. To serve with honor and dignity. Thats what they told us to do and thats what I did. For twenty-eight years.

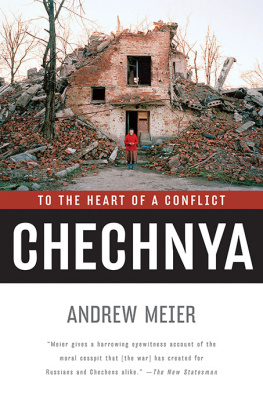

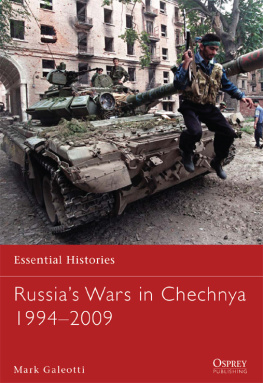

Andrei Sazykin died in the summer of 1996. He was killed on the northeastern edge of Grozny, before dawn broke on August 6, the parched day the rebels reclaimed their capital. The Chechens had swarmed back by the thousands. Seven other boys in his unit also fell that morning. Three weeks earlier Andrei had turned twenty.

For the Russian forces, the Sixth of August, as it became known, would live on. It would haunt them as a humiliation, the worst day of the war. For Andreis parents, Viktor and Valentina, it made no sense. They would sit in the dim light of their two-room apartment in Moscow and wonder how the Chechens had so easily retaken Grozny that day. Until the letters started to arrive. One after another, Andreis comrades began to write to his parents.

And suddenly, his father said, everything came into this terrible perfect clarity.

The letters were blunt.

Your son served well, recited Viktor. He had read the words a thousand times, but he traced the lines with his forefinger. In his voice there were tears. But he did not die in battle. He was sold down the river. We all were.

Valentina said the boys came to visit. They brought a video from their last days in Chechnya. It showed Russian officers, their shirts off in the severe heat of Grozny, playing backgammon with two Chechen fighters. They were smoking and drinking, all of them laughing.

That was the afternoon on the day before Andrei died, Viktor said. The boys later pieced it together. There was no battle that morning. There was a deal. The Chechens paid their way through the checkpoints. The boys were slaughtered. And when the others went looking for the commanders, they were gone.

Months after their sons death Viktor and Valentina brought a case, one of the first of its kind in Russia, against the Ministry of Defense. They sued to restore their boys honor and not, as the papers claimed, to get rich on compensation. They called his death a murder and vowed to seek punishment for those who killed him.

Several Augusts later, nearly five years to the day after their son died, I went to see them again. We had spoken in the intervening years. But I had never brought them the kind of news they craved, for I had failed to convince my editors that their sons case was a story. I had, however, followed Viktor and Valentina as they waged their long campaign. They had started in their neighborhood court and fought all the way to Russias Supreme Court. They even won a hearing in the Constitutional Court. But at every station they lost.

Along the way Valentina lost her job. For two decades she had taught biology in the local school. Viktor meanwhile had been forced to get a job. He now worked twenty-four-hour shifts, four times a week, at an Interior Ministry hotel, a hostelry for visiting officers in Moscow. Their savings depleted, they had also lost their hope. All they had, said Valentina, was nashe gore (our sorrow).

Tell me, Viktor said, fixing his eyes on mine. Because I cant understand it. But you must know. Can a country survive without a conscience?

In the days that followed our last conversation, I left Moscow after a stay of five winters and six summers. I had, truth be told, lived in the country for most of the last decade. I had seen out the last years of the Soviet experiment and witnessed the heady birth of the new Russia. I had seen the romantic rise of Boris Yeltsinand the wreckage his era wrought: the inglorious battle for the spoils of the ancient regime (an industrial fire sale of historic proportion), the military onslaught in Chechnya (the worst carnage in Russia since Stalingrad), and the rapid decline in nearly every index, social and economic, that the state took the trouble to record.

Next page

CONTENTS

CONTENTS