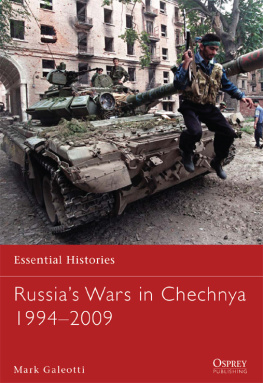

CHECHNYA

TO THE HEART

OF A CONFLICT

ANDREW MEIER

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint lines from Hadji Murad, in Leo Tolstoy, Master and Man and Other Stories, Penguin Classics, 1977, translated by Paul Foote.

The chapters in this book appeared in Andrew Meiers Black Earth: A Journey Through Russia After the Fall

Copyright 2005, 2003 by Andrew Meier

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Manufacturing by the Haddon Craftsmen, Inc.

ISBN 0-393-32732-9 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-393-34822-4 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

In memoriam

CONTENTS

One can transliterate the Russian language into Latin script variously. I have elected not to use the American scholarly standard, the Library of Congress system, in the hope of rendering the Russian as readable and recognizable as possible. (As such, the reader will find Yeltsin and not Eltsin.) With regard to translations, I have sought to use existing English texts whenever possible. Only when such translations do not exist or fall short of the Russian have I resorted to my own. Lastly, in a few rare cases, to protect the safety of individuals I have substituted names.

The way home was through a fallow field of black earth which had just been ploughed. I walked along the dusty, gently rising black-earth road. The ploughed field was squires land and very large, so that on either side of the road and on up the slope you could see nothing but black evenly furrowed fallow land, as yet unharrowed. The ploughing was well done and there was not a plant or blade of grass to be seen across the whole field: it was all black. What a cruel, destructive creature man is. How many different living creatures and plants he has destroyed in order to support his own life, I thought, instinctively looking for some sign of life in the midst of this dead black field.

Leo Tolstoy, Hadji Murad

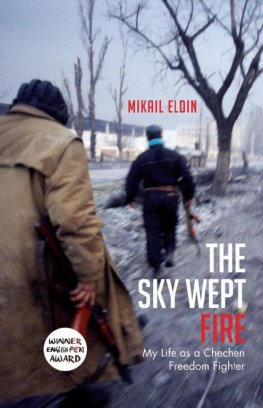

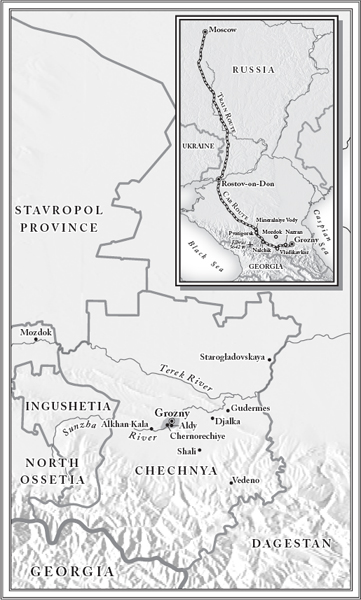

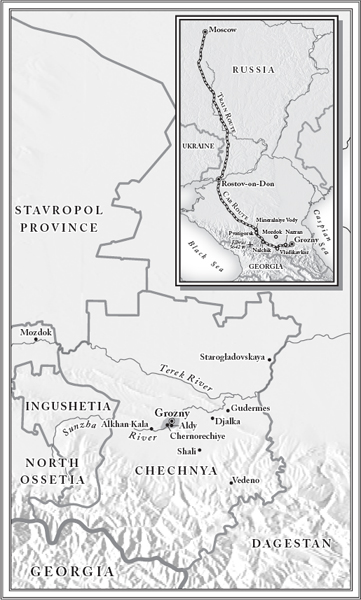

IT BEGAN WITH THE PLANES. On the night of August 24, 2004, nearly thirteen years to the day after the failed coup attempt against Mikhail Gorbachev, two Tupelov airliners disappeared, within minutes of one another, from the skies over Russia. A farmer near Rostov, years out of work and accustomed to the silence of the steppe, awoke to the buckle of noise. The sky had filled with a burst of light, he told the correspondent from state television. By daylight, the Russian authorities sought to cover up the cause, but all Russia knew the truth. A new season of terror had begun.

In the days that followed, it emerged that the planes had been blown uptwo Chechen women, the authorities would claim once they had pieced the evidence together, had traveled from Grozny, the Chechen capital, to a Moscow airport on a suicide mission. A week later, another Chechen woman walked beside a metro station in the center of Moscow, and just as the masses of commuters streamed out into the warm air, detonated a bomb, killing herself and taking ten innocents with her. All three were shakhidkifemale suicide bombers bent on martyrdom, the newest soldiers in the Chechen resistance.

Then came Beslan, the most horrific attack yet. In the far-off capitals of the West, the realm Russians have taken to calling the civilized world, the headlines would scream in shock. The terrorists had descended to a circle of evil without precedent. To target a schooltaking hostage more than a thousand innocent civilians, the majority of them women and children, was a nadir in the annals of terrorism. Russians watched the climax of the fifty-two-hour siege at Middle School Number One in horror. They remembered their Dostoyevsky. Etched in the collective memory was Ivan Karamazovs nihilist dictum: he could not believe in any God who would allow children to suffer at the hand of sadists.

We may never know the identities of all the men who held the school in North Ossetia hostage. At first, the FSB, the post-Soviet heirs of the KGB, said that ten Arabs had taken part in the attack. Vladimir Putin even repeated the claim, before his defense minister, Sergei Ivanov, a fellow KGB alumnus and the presidents closest confidante, refuted it. Among the terrorists corpses identified, Ivanov said, there were no Chechens. Yet that statement too, in the days that followed, was amended. Like the implausible turns of a Gogol short story, the Kremlin line seemed forever shifting, an account under construction with each new proclamation.

Under pressure, Putin made a rare concession: he vowed to open the sieges disastrous resolutionthe deaths of more than 350 civilians, half of them childrento an inquiry. Even in the loyal hands of the upper house of the Russian parliament, the investigation would mark a first for Russian history. In the wake of the seizure of the Moscow theater in the fall of 2002, when all 41 terrorists were killed but 130 hostages died from a military gas, Putin rejected any public reckoning. Instead, he promised an internal accounting that, somewhere in the years since it quietly stalled, was never to be completed.

Westerners look to a parliamentary inquiry and hope that the tragedy of Beslan may yield a salient lesson. Russians, however, being Russian, and still suffering the sins of Kremlin rulers past, have little faith in the states powers of self-examination. Putin, they knew, would rage on about the toll of terror. But the families of the hundreds who died at Beslan, and the millions of Russians who now faced a new fear from St. Petersburg to Vladivostok, expected little to change. The state would redraw its hard line across Chechnya, proclaim yet again a promise of protection, and, all too predictably, leave the survivors alone to search for solace. Putin, at the same time, in the name of the antiterrorism fight, would grab yet more power.

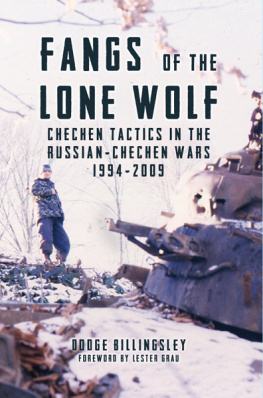

RUSSIAS TROUBLES with Chechnya, despite what Putin and his appeasers in the West would claim, did not begin with September 11. The Chechens have yearned for freedom since the days of Catherine the Great. The present troubles have flitted on and off Americas television screens for a decade now. On November 26, 1994, Boris Yeltsin and the heirs of the KGB staged a proxy attack in Grozny against the wayward provinces newly risen separatist ruler, a recently retired Soviet air force general named Djokhar Dudayev. As the Soviet monolith disintegrated, and independence movements rent the old empire, Dudayev had come home to lead a rebellion. In late 1991, backed by a crew that was part criminal, part partisan, and all nationalist, he unilaterally proclaimed an independent Chechen republic.

Moscows counterinsurgency proved hapless and bloody, a post-Soviet Bay of Pigs. Yet it was only a prelude to the onslaught that followed. On December 31, 1994, when Yeltsin then sent hundreds of tanks into the center of Grozny, the first war commenced. It would be, Yeltsin was assured, a small, victorious war, in the words of a minister under the Romanovs. It was a campaign of blundering Russian generals and ardent Chechen guerrillas, waged with little attention on either side to the niceties of the Geneva Conventions. For the Russians, the war soon turned into a costly, and deeply unpopular, quagmire. In 1996, a Russian provincial governor would circulate a petition demanding its end, and promptly collect a million signatures. For the Chechens, however, it was a war of infinite passion and pride. It was a time of ascendant heroes, men who rose from obscurity to find fame in the bloodshed. Men like Shamil Basayev, a young commander born under Khrushchev, and named in honor of the Caucasuss most fabled warrior, Imam Shamil, leader of the mountaineers nineteenth-century campaigns against the tsars.

Next page