A DIRTY WAR

A Russian Reporter in Chechnya

ANNA POLITKOVSKAYA has been a special correspondent for the bi-weekly Russian newspaper Novaya gazeta (circulation 700,000) since 1999. After graduating from the Journalism Faculty of Moscow University in 1980, she worked first for the Izvestiya daily, and then, in the 1990s, for the Megapolis Express and Obshchaya gazeta weeklies. She has made social issues her subject: public mores, the defective judicial system, prison conditions, and the fate of orphans, the disabled and the country's many refugees and displaced persons. In January 2000 she was awarded the prestigious Golden Pen Award by the Russian Union of Journalists for her outspoken coverage of the new federal campaign in Chechnya.

JOHN CROWFOOT lived in Moscow from 1986 to 1999. In the early 1990s he worked with Express Chronicle human rights weekly and Vozvrashchenie publishers. Among his translations from the Russian are Vitaly Shentalinsky's The KGB's Literary Archives, Lev Razgon's True Stories and an anthology of women's memoirs of the Gulag, Till My Tale is Told. He is currently translating the memoirs of Emma Gerstein.

THOMAS DE WAAL reported on Russia and the Caucasus from 1993 to 1999 for the Moscow Times, The Times, the Economist and the BBC World Service. With Carlotta Gall, he won a James Cameron Prize for Outstanding Reporting for their book Chechnya: A Small Victorious War (1997). He is now based in London and working on a book about the Nagorny Karabakh conflict.

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9781407018287

Version 1.0

www.randomhouse.co.uk

First published in Novaya gazeta

First published in Great Britain in 2001 by The Harvill Press

10 12 14 16 18 19 17 15 13 11

Copyright Anna Politkovskaya, 1999

English translation copyright John Crowfoot, 2001

Introduction copyright Thomas de Waal, 2001

Anna Politkovskaya has asserted the right under the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1998 to be identified as the author of this work

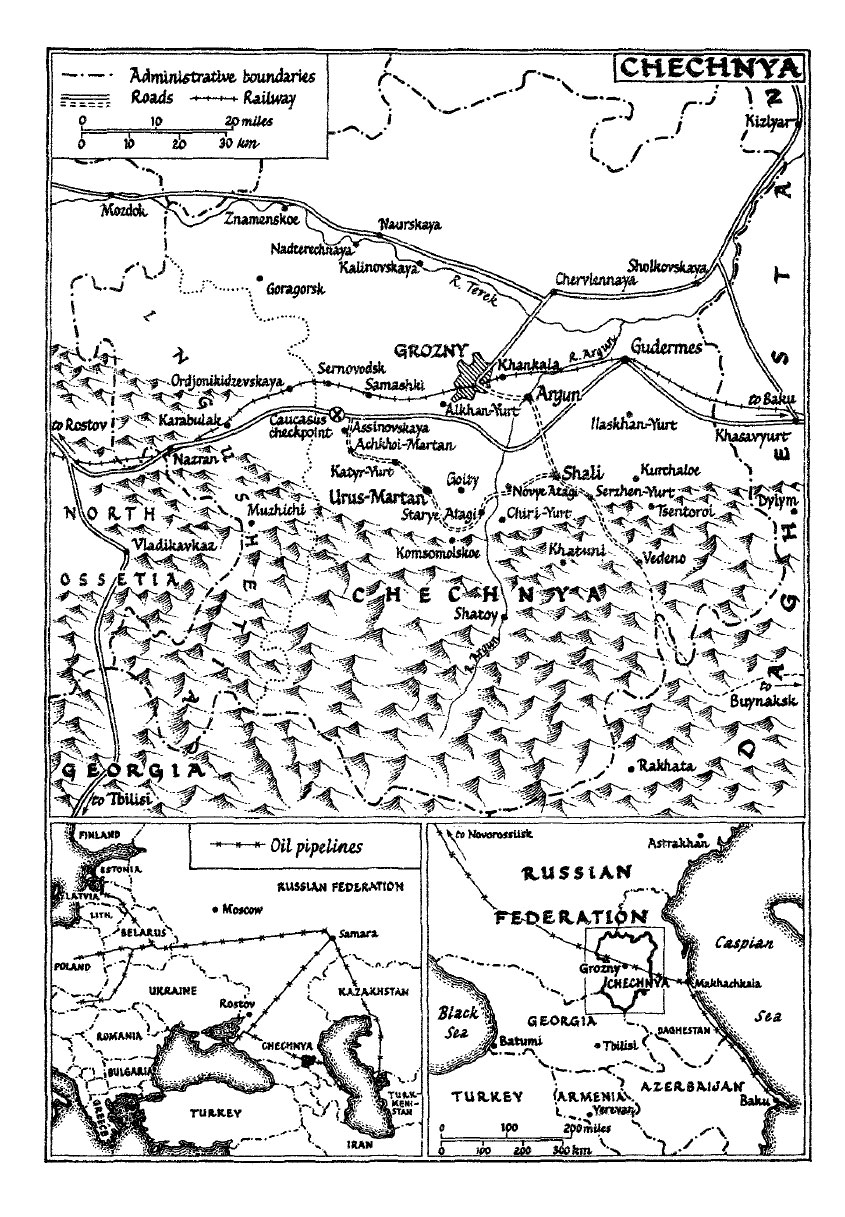

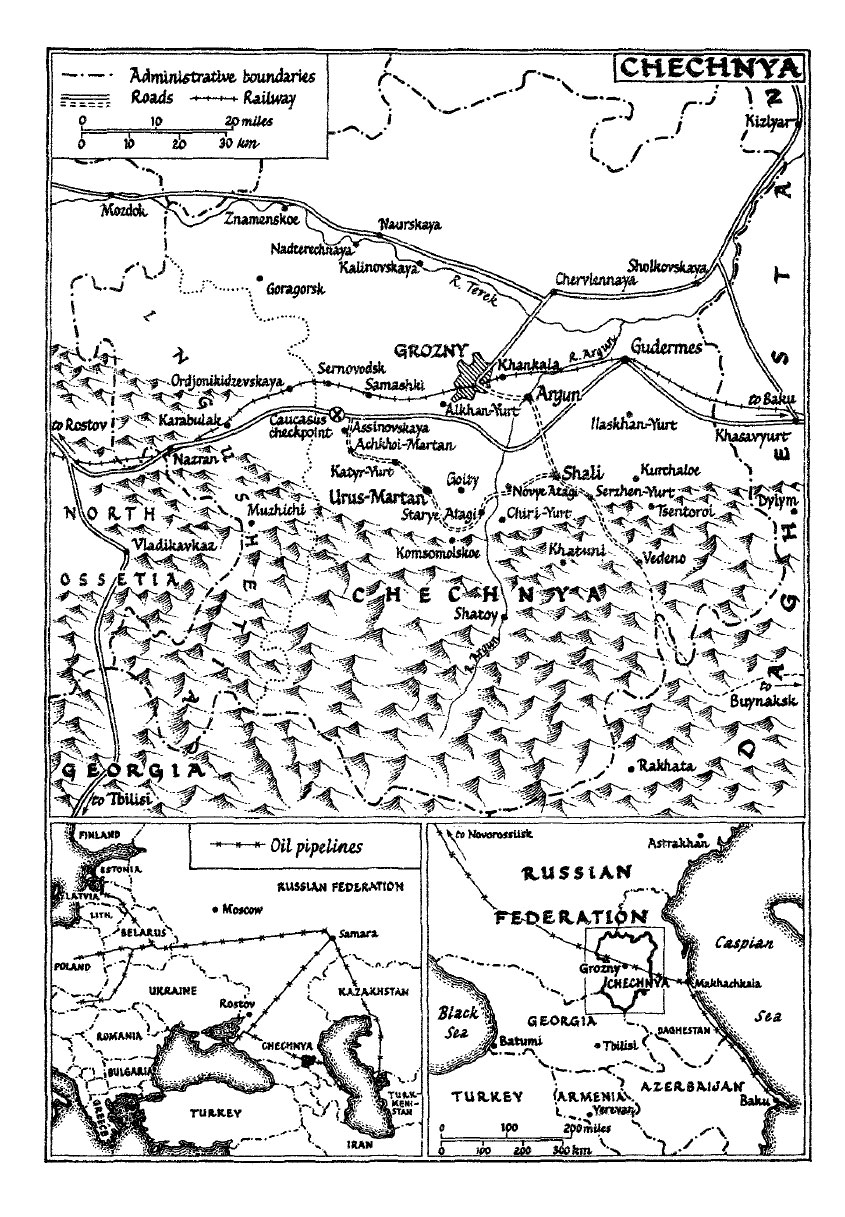

All maps by Reginald Piggott

This electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

The Harvill Press

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road

London SW1V 2SA

Random House Australia (Pty) Ltd

20 Alfred Street, Milsons Point, Sydney

New South Wales 2061, Australia

Random House New Zealand Ltd

18 Poland Road, Glenfield

Auckland 10, New Zealand

Random House (Pty) Limited

Isle of Houghton, Corner of Boundary Road & Carse O'Gowrie,

Houghton 2198, South Africa

Random House Publishers India Private Limited

301 World Trade Tower, Hotel Intercontinental Grand Complex,

Barakhamba Lane, New Delhi 110 001, India

Random House UK Ltd Reg, No. 9S4009

www.randomhouse.co.uk

ISBN: 9781407018287

Version 1.0

PREFACE

On 11 December 1994 Russian forces were sent into Chechnya "to restore the constitutional order" after three years of tension and uncertainty. "Why can't we carry out an operation in our country like the US did in Haiti?" demanded Kremlin hawk Oleg Lobov when warned of the possible consequences. Whether the attitudes of the war-party were shaped by contempt or historical ignorance, the use of force turned a minor distraction into a major conflict.

The Chechen fighters denied the federal authorities a rapid victory. The generals and politicians leading the campaign had to face the unaccustomed scrutiny of Russia's new media and parliament. A small but articulate minority in Moscow opposed the operation from the outset and mounting casualties extended public disaffection: a year later Boris Nemtsov, young governor of the Nizhny Novgorod Region, gathered a million signatures on a petition against the war. Finally, after 18 months of armed conflict and uneasy ceasefires, the stalemate was officially acknowledged.

Following Yeltsin's re-election as President of the Russian Federation (and a last outburst of fighting), an agreement was reached with Chechnya's leaders in August 1996. Federal troops were withdrawn, and a five-year moratorium imposed on any discussion of the republic's disputed status. The war had been a terrible and disturbing lesson for the reformers.

A mere ten years earlier the USSR was a nuclear superpower and serious rival to the West. The rapid dissolution of the Soviet bloc and the emergence of more than a dozen new states from the USSR was "in retrospect a remarkably non-violent process"Soviet Union.

In January 1997 Asian Maskhadov was chosen President of Chechnya in elections that international monitors agreed were free and fair. In May that year he met President Yeltsin and they signed a treaty that further confirmed the end of hostilities. Both sides seemed determined henceforth to resolve their differences by non-violent means. This commitment to democracy and diplomacy justified Russia's admission to the Council of Europe in 1996. In international eyes Chechnya remained within the Russian Federation, and was thus also regarded as part of a wider Europe.

However, others drew a different lesson from the first military campaign. If such an operation were repeated, the government was advised, the forces sent into Chechnya should be properly led and co-ordinated; and this time public opinion, the media and parliament would have to be effectively prepared and managed. When Anna Politkovskaya began reporting for the popular bi-weekly Novaya gazeta in summer 1999, Yeltsin was selecting a new prime minister. The little-known Vladimir Putin's candidacy benefited from a widespread feeling that the country needed firmer government, that the new business magnates, the so-called oligarchs, should be reined in and that the Federation's 89 restive regions and republics ought to be brought back under control. With parliamentary elections soon to be held, a rapidly escalating sequence of events provided an opportunity for Yeltsin's protg to give a dramatic demonstration of such firmness fighting in Daghestan, terrorist explosions in Moscow and the second deployment of federal forces in Chechnya on I October 1999.

JOHN CROWFOOT

INTRODUCTION

In 1818 the tsarist general Alexei Yermolov founded a new fortress in the North Caucasus. He was stepping up his efforts to subdue the rebellious native peoples in the mountains to the south and he called the fortress Groznaya, meaning "Terrible" or "Formidable", as a token of his intent to intimidate them. How grimly appropriate then that the city of Grozny, the successor to that fortress, should now symbolise the terror that the Russian military can inflict in the modern age. Grozny, which once had a population of 400,000, is now barely a city at all. All its major buildings stand in ruins. It is modern Europe's most powerful symbol of what happens when politics fails and violence takes over.