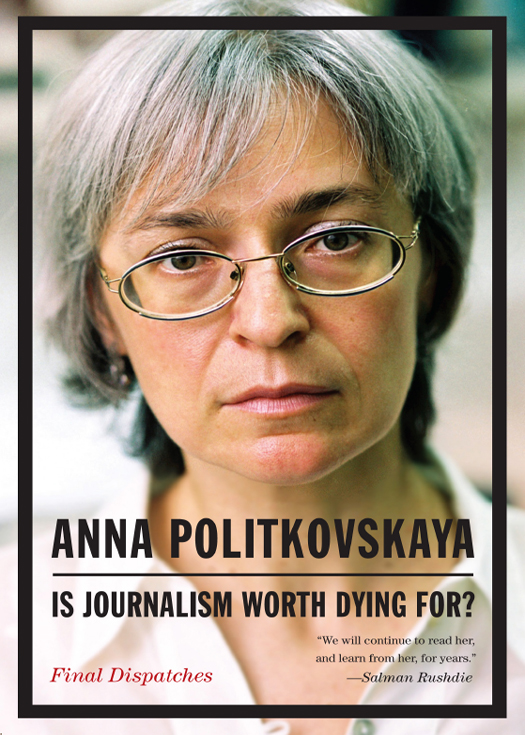

Known by many as Russias lost moral conscience and hailed by the New York Times as the bravest of journalists, ANNA POLITKOVSKAYA (born 1958 in New York City) was a special correspondent for the Russian newspaper Novaya gazeta. She received honors from many Russian and international groups, including Amnesty International and the Index on Censorship. In 2000 she received Russias prestigious Golden Pen Award for her coverage of the war in Chechnya, and in 2005 she was awarded the Civil Courage Prize. She is the author of A Dirty War; A Small Corner of Hell; Putins Russia; and A Russian Diary. She was murdered in Moscow on October 7, 2006.

ARCH TAIT translates from the Russian. His translation of Ludmila Ulitskayas Sonechka: A Novella and Stories was shortlisted for the Rossica Translation Prize in 2007.

Also by Anna Politkovskaya

A Russian Diary

Putins Russia

A Small Corner of Hell: Dispatches from Chechnya

A Dirty War: a Russian Reporter in Chechnya

IS JOURNALISM WORTH DYING FOR?

Originally published in Russian as Za chto?

by Novaya gazeta, Moscow, 2007

2007 Anna Politkovskaya

2007 Novaya gazeta

Translation 2010 by Arch Tait

First Melville House printing: March 2011

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.mhpbooks.com

eISBN: 978-1-935554-70-7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011922469

v3.1

This book was first published in Russian as Za chtoWhat For?by Novaya gazeta, the newspaper to which Anna Politkovskaya contributed from June 1999 until her murder in October 2006. Her colleagues at the paper assembled the collection, and their reminiscences of Politkovskaya and investigation of her murder (including Vyacheslav Izmailovs Who Killed Anna and Why?) are also included. Politkovskaya is one of four Novaya gazeta journalists murdered between 2001 and 2009.

CONTENTS

She represented the honor and conscience of Russia, and probably nobody will ever know the source of her fanatical courage and love of the work she was doing.

Liza Umarova, Chechen singer

Anna rang me at the hospital in the morning, before 10 oclock. She was supposed to be coming to visit, this was her day, but something had come up at home. Anna said my second daughter, Lena, would come instead, and promised that we would definitely meet on Sunday. She sounded in a good mood, her voice was cheerful. She asked how I was feeling and whether I was reading a book. She knew I love historical literature and had brought me Alexander Mankos The Most August Court under the Sign of Hymenaeus. She had not read it herself. I said, Anya, it is difficult for me to read. I have to read every page three times because I have Father before my eyes all the time. [Raisa Mazepas husband had died shortly before.] She tried to calm me, He didnt suffer. Everything happened very quickly. He was coming to visit you. Lets talk about the book instead. I said, Anya there is an epigraph on page 179 which really moves me. It is so much a part of us, so Russian. I read it to her: There are drunken years in the history of peoples. You have to live through them, but you can never truly live in them.

Oh, Mum, she replied, put a bookmark there, dont forget. I asked my daughter who the author of the epigraph was, and she told me about Nadezhda Teffi, a famous Russian poetess. Then she said, Speak to you tomorrow, Mum. She was in a very good mood. Or perhaps she was in a bad mood and just pretending everything was fine in order not to upset me.

I was always very worried about her. Shortly before I went into hospital we had a talk. She was preparing an article about Chechnya, and I simply begged her to be careful. I remember she said, Of course I know the sword of Damocles is always hanging over me. I know it, but I wont give in.

Raisa Mazepa (Anna Politkovskayas mother), Novaya gazeta,

October 23, 2006

SO WHAT AM I GUILTY OF?

This article was found in Anna Politkovskayas computer after her death and is addressed to readers abroad.

Koverny, a Russian clown whose job in the olden days was to keep the audience laughing while the circus arena was changed between acts. If he failed to make them laugh, the ladies and gentlemen booed him and the management sacked him.

Almost the entire present generation of Russian journalists, and those sections of the mass media which have survived to date, are clowns of this kind, a Big Top of kovernys whose job is to keep the public entertained and, if they do have to write about anything serious, then merely to tell everyone how wonderful the Pyramid of Power is in all its manifestations. The Pyramid of Power is something President Putin has been busy constructing for the past five years, in which every official from top to bottom, the entire bureaucratic hierarchy is appointed either by him personally or by his appointees. It is an arrangement of the state which ensures that anybody given to thinking independently of their immediate superior is promptly removed from office. In Russia the people thus appointed are described by Putins Presidential Administration, which effectively runs the country, as on side. Anybody not on side is an enemy. The vast majority of those working in the media support this dualism. Their reports detail how good on-side people are, and deplore the despicable nature of enemies. The latter include liberally inclined politicians, human rights activists, and enemy democrats, who are generally characterised as having sold out to the West. An example of an on-side democrat is, of course, President Putin himself. The newspapers and television give top priority to detailed exposs of the grants enemies have received from the West for their activities.

Journalists and television presenters have taken enthusiastically to their new role in the Big Top. The battle for the right to convey impartial information, rather than act as servants of the Presidential Administration, is already a thing of the past. An atmosphere of intellectual and moral stagnation prevails in the profession to which I too belong, and it has to be said that most of my fellow journalists are not greatly troubled by this reversion from journalism to propagandising on behalf of the powers that be. They openly admit that they are fed information about enemies by members of the Presidential Administration, and are told what to cover and what to steer clear of.

What happens to journalists who dont want to perform in the Big Top? They become pariahs. I am not exaggerating.

My last assignment to the North Caucasus, to report from Chechnya, Ingushetia, and Dagestan, was in August 2006. I wanted to interview a senior Chechen official about the success or failure of an amnesty for resistance fighters which the Director of the Federal Security Bureau, the FSB, had declared.

I scribbled down an address in Grozny, a ruined private house with a broken fence on the citys outskirts, and slipped it to him without further explanation. We had talked in Moscow about the fact that I would be coming and would want to interview him. A day later he sent someone there who said cryptically, I have been asked to tell you everything is fine. That meant the official would see me, or more precisely that he would come strolling in carrying a string bag and looking as if he had just gone out to buy a loaf of bread.