F RONT L INES to H EADLINES

The World War I Overseas

Dispatches of Otto P. Higgins

J AMES J . H EIMAN

Kansas City

C opyright 2019 James J. Heiman

Published by Woodneath Press

8900 NE Flintlock Rd.

Kansas City, MO 64157

Cover design: Amber Noll

All rights reserved. This book, or part thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without the written permission from the publisher or author, except for the inclusion of brief passages in a review.

Publishers Cataloguing-in-Publication

(Provided by Woodneath Press: A Program of Mid-Continent Public Library)

Heiman, James J.

Front Lines to Headlines: The World War I Overseas Dispatches of Otto P. Higgins / James J. Heiman

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-942337-09-6

- History / Military / World War I

- Photography / Photojournalism

- History / Military / Wars & Conflict (Other)

For Otto P. and Higgi

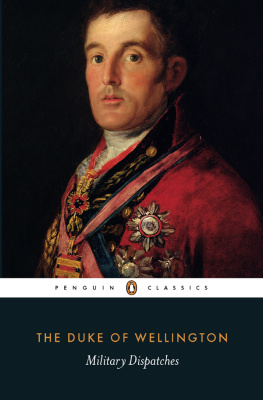

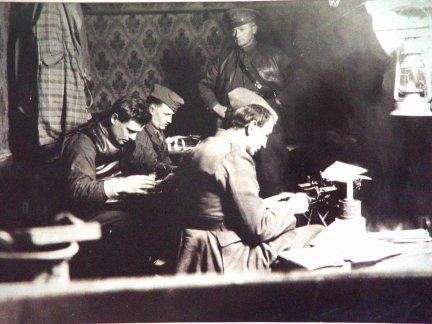

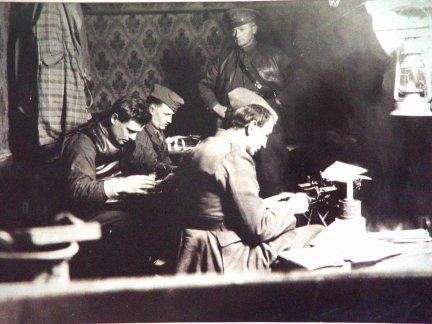

The one remaining room of a house in Brandeville, France, on the march into Germany. November 20, 1918

Left to Right: William Slavens McNutt of Colliers , Raymond S. Tompkins of the Baltimore Sun, Bernard S. ODonnell of the Cincinnati Enquirer , and foreground, Otto P. Higgins of the Kansas City Star .

(That Job of Writing Up the War, the Kansas City Star, June 8, 1919, 15C.)

This photograph was taken on November 20, 1918. OPH is pictured in the foreground to the right. He is typing a letter to his wife, Elizabeth, and in the letter OPH indicated that the photo had been staged for effect.

The fact of the matter is, the War Department wants a picture of newspaper correspondents at work, OPH wrote, and so four of us gathered around the fire working, while they took a flashlight of us. So you see this page is only just a joke, but I thought I would write it to you so you would know that I was thinking about you, even though I was having my picture taken with a lot of highbrow correspondents and magazine writers. Now that the picture is finished I am going to tell you good night, and tomorrow, maybe if we can get a place to stay, I will write some more.

Although the photo itself was staged, still it represented the reality of the conditions under which the stories were written. OPH explains and comments about the setting: Only using one candle tonight. Have it sitting on a bench, then a roll of toilet paper, then a tin can, and then the candle, so I can see the keys on my machine. But we dont mind little things like that over here anymore. Dont know what I would do with electric lights. Candles furnish mighty good power, and I always carry two or three in my musette bag.

We are going to move early in the morning to Montmedy. I dont know why it is that I have been thinking of you so much lately, unless that it is that we are living in what was once a French home, but now is only two rooms, one of which we use for a bedroom and the other for an office and workroom. We have a wonderful fireplace in it, but no windows, and as a result it is hot on one side and cold on the other. When the wood runs low we just tear a timber loose from the roof and throw it on the fire, or else rustle a table leg or a bedstead, or something like that. It makes a wonderful fire and a beautiful thing to look at, but it smokes like the devil and makes you as sleepy as can be.

[Letter from collection of Sheila Scott, personal communication August 28, 2011].

A Note on OPHs Text

Wherever possible, I have tried to maintain the text and formatting of articles as they were published in the Star . However, if spelling, punctuation, or sentence structure in the original would confuse or otherwise distract todays reader from the content of the article, I modernized original text conventions to accommodate meaning. Occasionally, while attempting to document the service record or biographical details of a subject OPH mentions, I discovered that the spelling of the name was inconsistent. Given the oral nature of newspaper reporting, especially in a war zone, the reporter or re-write editors at the Star offices, often relied on a phonetic spelling. In those situations, I maintained the spelling as it appeared in print, and I indicated the alternate spelling and source in an endnote.

Table of Contents

A mericas entry into the Great War launched an unprecedented movement from the new world to the old. Over a million American men and women would cross the U-boat filled Atlantic headed for the titanic struggle in Europe. These soldiers and sailors took with them all the necessary tools of wareverything from rifles, horses, aircraft, food, fuel, paperwork, and all the many other implements necessary for fighting the crusade over there.

The still young and brash United States watched with anticipation and unease as its youth sailed overseas. Yielding to the demand for information about the troops, General John J. Pershing reluctantly accredited a select group of war correspondents. Initially their number was small, but over time Pershing came to recognize their value to the war effort. More eager journalists would be given an army uniform and inserted into the epic supply chain to Europe.

As accredited reporters, they hoped for greater access than the freelance journalists who would also find their way to France. One of those accredited correspondents was 27-year-old Otto Higgins, representing The Kansas City Star . When he and the others arrived at the front lines, they would see first hand that this was a new kind of war. Their newspaper dispatches would describe a modern conflict where technology and mass production combined to produce horrific casualties in numbers never seen before. They would struggle to overcome the wartime censors, and to convey the full magnitude of their experience while balancing patriotism with objectivity. Without TV, smartphones, internet, or even radio as a mass medium, it is hard for us today to imagine the importance of their dispatches. They had a solemn responsibility to millions of readers around the world.

Although the Great War raged from 1914 to 1918, the US was a late entry, declaring war in April 1917. By the time the guns fell silent on the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, the world, and journalism, would never be the same. As Otto Higgins and his colleagues headed home, they must have felt certain they had just covered the story of the century. They could not know that the war to end all wars would be followed by another world war roughly two decades later. The rush of history is relentless. Over time, the World War I reports of correspondents like Higgins would be too often forgotten. Fortunately for posterity, Higgins wife Elizabeth had collected clippings of his dispatches, storing them in an old steamer trunk. After he returned home from Europe, Higgins would add his field notes, photographs, military passes and other materials.

Next page