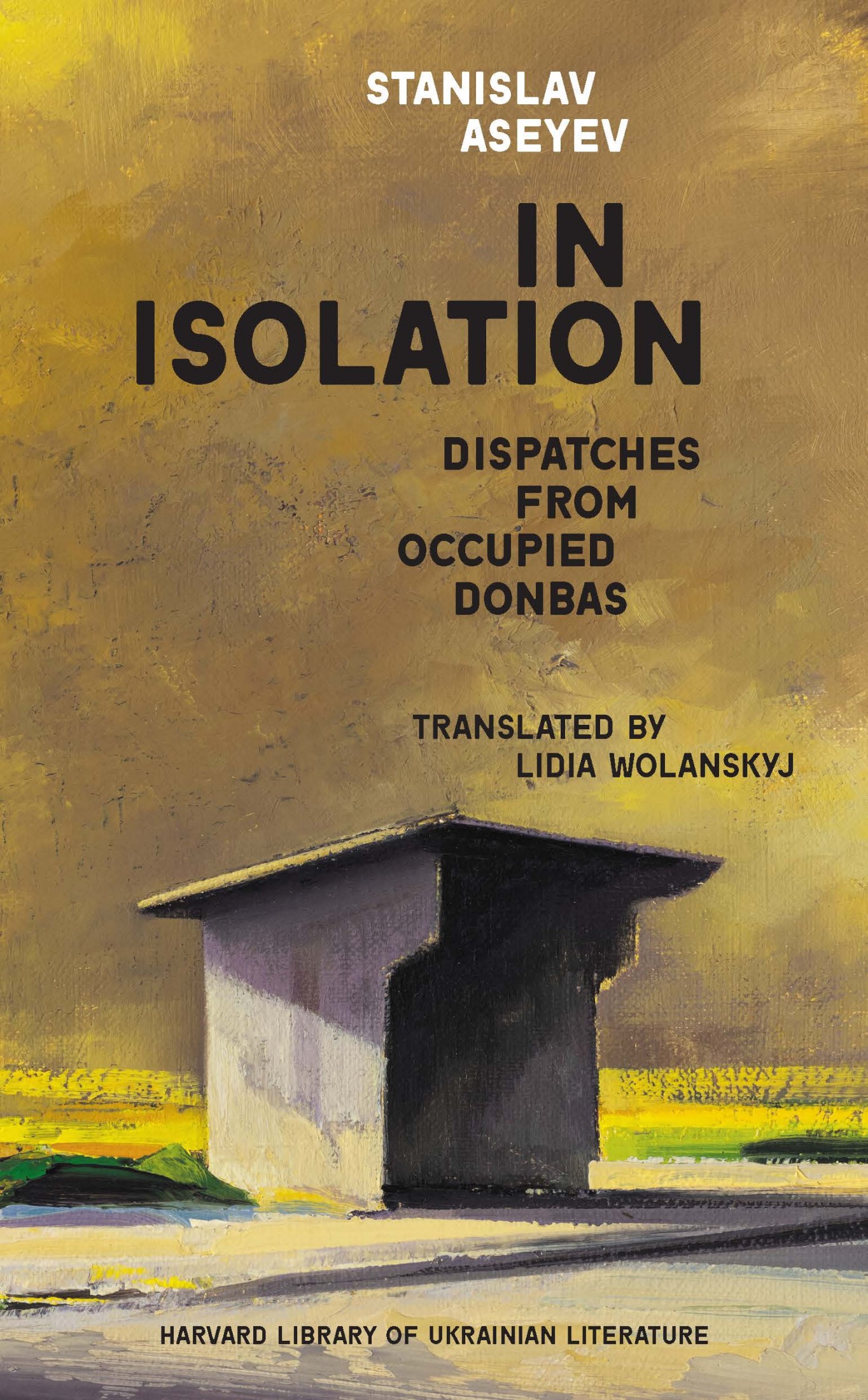

In Isolation

Ukrainian Research Institute

Harvard University

Harvard Library of Ukrainian Literature 1

HURI Editorial Board

Michael S. Flier

George G. Grabowicz

Oleh Kotsyuba, Manager of Publications

Serhii Plokhy, Chairman

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Stanislav Aseyev

In Isolation

Dispatches from Occupied Donbas

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Distributed by Harvard University Press for the Ukrainian Research Institute Harvard University

The Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute was established in 1973 as an integral part of Harvard University. It supports research associates and visiting scholars who are engaged in projects concerned with all aspects of Ukrainian studies. The Institute also works in close cooperation with the Committee on Ukrainian Studies, which supervises and coordinates the teaching of Ukrainian history, language, and literature at Harvard University.

2022 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Printed in the U.S. on acid-free paper

ISBN 9780674268784 (hardcover), 9780674268791 (paperback), 9780674268814 (epub), 9780674268807 (PDF)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021948577

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021948577

Commentary in the editorial notes and the timeline of events by Oleh Kotsyuba, edited by Michelle R. Viise

Maps by Kostyantyn Bondarenko, MAPA: Digital Atlas of Ukraine , Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard University, https://huri.harvard.edu/mapa

Timeline design by Mykola Leonovych, background maps source: ZomBear, Marktaff, War in Donbas, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_in_Donbas

Cover image: Wilhelm Neusser, Bus Stop / Yellow Cloud (#2011), 2020. Reproduced with permission from the artist and Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, Boston, Mass.

Stanislav Aseyev photo courtesy of Radio Svoboda (RFE/RL)

Book design by Mykola Leonovych, https://smalta.pro

Publication of this book has been made possible by the Ukrainian Research Institute Fund and the generous support of publications in Ukrainian studies at Harvard University by the following benefactors:

Ostap and Ursula Balaban

Jaroslaw and Olha Duzey

Vladimir Jurkowsky

Myroslav and Irene Koltunik

Damian Korduba Family

Peter and Emily Kulyk

Irena Lubchak

Dr. Evhen Omelsky

Eugene and Nila Steckiw

Dr. Omeljan and Iryna Wolynec

Wasyl and Natalia Yerega

You can support our work of publishing academic books and translations of Ukrainian literature and documents by making a tax-deductible donation in any amount, or by including HURI in your estate planning. To find out more, please visit https://huri.harvard.edu/give.

Translation of this book was prepared within the PEN Ukraine Translation Fund Grants program in cooperation with the International Renaissance Foundation.

Publication of this book was made possible, in part, by the Translate Ukraine Translation Program of the Ukrainian Book Institute (Ukraine).

Publication of this book was made possible, in part, by a translation grant from the Peterson Literary Fund at BCU Foundation (Toronto, Canada). The Peterson Literary Fund recognizes the best books that promote a better understanding of Ukraine or the Ukrainian people, or whose subject matter is relevant to a global Ukrainian audience.

From the Editors

In this book, transliteration of personal and place-names follows a modified Library of Congress system for Ukrainian and Russian. With the exception of the name for Kyivan Rus, primes for the soft sign () and other diacritics are omitted (thus Luhansk and Lysychansk rather than Luhansk and Lysychansk), while apostrophes are retained (as in Sloviansk and Prypiat). In personal names where a vowel follows a soft sign in the original, the letter i is used to indicate softness (as in Aksionov and Kiseliov). Toponyms are usually transliterated from the language of the country in which the designated places are currently located, including the Ukrainian letter i with diaeresis (), except for the capital of Ukraine, thus yielding Kyiv, Odesa, Lviv, Makivka, Avdivka, etc. Furthermore, well-known personal and place-names appear in spellings widely adopted in English-language texts (thus Yanukovych rather than Ianukovych and Moscow rather than Moskva).

Editorial commentary and the timeline of events leading to and during the war in Donbas were prepared by Oleh Kotsyuba and edited by Michelle R. Viise. Translators notes were prepared by Lidia Wolanskyj and Anna Korbut.

In the course of translation and editing of the book, the author approved revisions of a number of passages and turns of phrase in portraying certain female and male protagonists, including those suffering from addictions, referring to geographic locations and stereotypes associated with them in Ukraine and Russia, and comprising metaphors that would be alien to an Anglophone audience.

Road signs for Makivka and Donetsk, with Msta-B 152 mm howitzers on the road.

Preface

By the time the Ukrainian edition of this book came out, I had already spent a year in a special prison for exceptionally dangerous persons in the city of Donetsk. I had been locked up there for my political views and for the articles I had published in the Ukrainian press about life in the Donbas. My prison was located on the grounds of Izoliatsiia, formerly an insulation manufacturing plant; today it has earned a bitter reputation as a modern-day concentration camp. In part, thats where the name of the book In Isolation comes from; it refers to my imprisonment and contains the observations that I recorded while working as a journalist in the Donbas.

But the term izoliatsiia refers to more than just a jail. It also denotes the feeling that functions as the leitmotif of this book, the sense of aloneness and isolation I experienced every day, when forced to hide under the pseudonym Stanislav Vasin in my own land in order to be able to write about the things that you will find in the pages of this book. Despite my use of a pseudonym, I was still found out and arrested by pro-Russian insurgents and thrown into Izoliatsiia for twenty-eight months. This occurrence still holds some mystery for me, as my arrest was definitely no accident. To this day I have no idea how these people tracked me down.

Oddly enough, even after my arrest, while I was being held in a basement, my captors forced me to pretend for nearly a month that I was still free: to call family and friends, to keep posting comments to Facebook, and even to write articles. In fact, the last chapter of this book, A Knack for Losing Things, was an article written by me in that prison basement. It was included in the Ukrainian edition of this book by editors who had no idea of the circumstances under which I had written the piece. Indeed, when I asked my captors to give me a pencil and paper, they refused. I had to come up with the article overnight, which meant composing it entirely in my head so that I could quickly produce it in electronic form the following day and send it off to the editorial office. Curiously, my captors were not the least bit interested in censoring the content of my article: for some reason, it was more important for them that no one raise the alarm that I had been arrested.