Table of Contents

All Nature seemed filled with peace-giving power and beauty.

Is there not room enough for men to live in peace in this magnificent world, under this infinite starry sky? How is it that wrath, vengeance, or the lust to kill their fellow men can persist in the soul of man in the midst of this entrancing Nature? Everything evil in the heart of man ought, one would think, to vanish in contact with Nature, in which beauty and goodness find their most direct expression.

War? What an incomprehensible phenomenon! When reason asks itself, is it just? is it necessary?, an internal voice always answers no. Only the permanence of this unnatural phenomenon makes it natural, and only the instinct for self-preservation makes it just.

Who would doubt that, in the war between the Russians and the mountain people, justice, stemming from the instinct for self-preservation, is on our side? If not for this war, what would protect all our neighboring rich and enlightened Russian territories from robbery, murder, and raids by savage and warlike peoples? But let us consider two particular people.

Who has the instinct for self-preservation and, consequently, justice on his side? Is it on the side of some pauper named Jemi who, hearing of the approach of the Russians, swears, takes his old rifle from the wall, and, with three or four rounds that he doesnt intend to waste, runs to meet the giaours? Of Jemi, who has seen how the Russians keep advancing toward his planted field, which they will trample, toward his hut, which they will burn down, and toward the ravine where his mother, wife, and family, trembling with fear, are hiding? Who thinks that they will take everything from himeverything that gives him happiness? Who, full of impotent rage, utters a cry of despair, tears off his tattered homespun coat, flings his rifle to the ground, pulls his cap down over his brows and, singing his death song, hurls himself headlong against the bayonets of the Russians with only his dagger in his hand?

Is justice on his side, or on the side of the officer from the generals staff who sings French songs so well just as he passes us? Back in Russia he has a family, relatives, friends, serfs, and responsibilities to them, he has no cause or desire to fight with the mountain people, but he has come to the Caucasus... to show how brave he is! Or is it on the side of an aide-de-camp I know, who wants only to attain the rank of captain and a cushy job, and has therefore become an enemy of the mountain people?

From an early draft of The Raid: A Volunteers Story, written 150 years ago, in 1852, by the twenty-four-year-old army officer Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy

INTRODUCTION

WHOSE TRUTH?

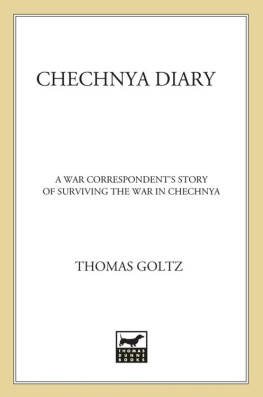

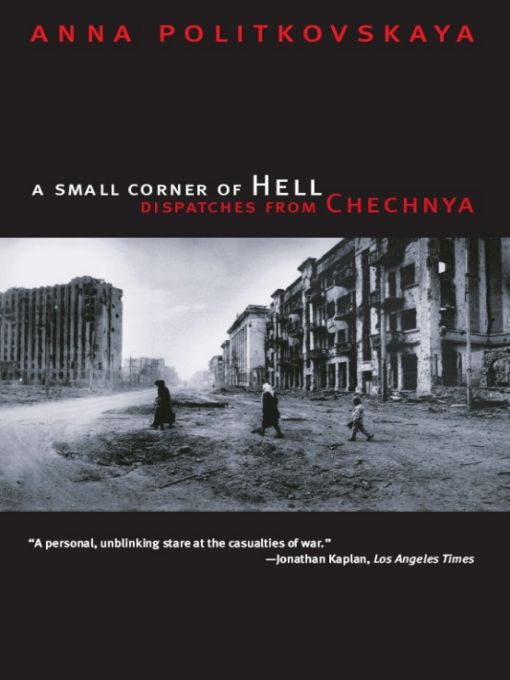

The first question to be addressed inevitably is, why read this book? Much of the book consists of personal stories; many of the people of whom those stories are told are no longer alive. Anna Politkovskaya is unsparing in presenting the brutal realities of war, and reading such a book requires moral labor. Perhaps this is because by learning about Chechnya we learn not only about a wretched corner of postcommunist eastern Europe, but something important regarding the whole world where we all live. It is a substantially more complex and often more tragic world than suggested by the upbeat futuristic portrayals of globalization during the market boom of the 1990s. Acts of terrorist violence, such as the attacks of September 11 in America, the recurring suicide bombings in Israel, and the seizure of a Moscow theater in October 2002, present a spectacularly ghastly facet of a new global reality. Whatever might be the fashionable opinion, the world situation is not reducible to a clear-cut conflict of backward fanatical terrorists assaulting the realm of civilized urbanity. Fortunately, the real world is more complex; fortunate indeed, because the realization of the worlds complexity and interdependency might allow us to discuss and seek different ways of coping with new global dilemmas than propagandistic calls for all-out war on terror would suggest. Politkovskaya accomplishes her task by showing the contradictory complexity of the human condition in an otherwise absolutely inhuman situation.

Is this account of the war in Chechnya to be trusted? Or, in the language of social science, how valid are the data and analysis that organize the presentation? This is a very contentious question. Many important people in Moscow routinely call Politkovskayas reporting too sensationalist and lacking in patriotism, especially as Russia fights what they describe as the threat of Islamic terrorism. And indeed, the radical wing of Chechen insurgency under the command of Shamil Basayev uses Islamic rhetoric to justify acts that many would call terrorist: hijackings, taking hostages, car bombings.

As in all violent conflicts, the belligerents present diametrically opposed versions of events in support of their political claims and tactics. It would be nave to seek the truth somewhere in between these mirror-image extremes. It is equally futile to assume that outside observersthird-party diplomats, aid providers, scholarly experts, or investigative journalistscould be totally unbiased in their presentations. Then how can we decide which truth about the war in Chechnya is better?

The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu suggested a promising way out of this conundrum. To decide consciously, we must make an effort to know what kind of people or organizations produced the accounts of events and what might be their agendas, and then we should ask ourselves how it relates to the kind of person we think we are and what shapes our own attitudes. Instead of striving for abstract objectivity (which usually ends in pretentious hypocrisy and sermonizing), Bourdieu advised us to grasp the whole field of social relations, for example the intersecting field of politics or journalistic production.

Furthermore, the stakes proper to each field must be clarified. For instance, the stakes in capitalist markets clearly are monetary profits; in science it might be the thrilling sensation of making a discovery and recognition of ones intellectual stature by colleagues; in the arts it is the acclaim of fellow artists, critics, and spectators. Public acclaim and professional recognition surely matter in political journalism too. But in this field the importance of such considerations might fade away during periods of acute political struggle, when people come to consider the stakes much more important than their personal interest or even life itself. For the sake of professional success Politkovskaya could have chosen a less grievous and dangerous topic to write about. More than two dozen journalists have been killed in Chechnya since the beginning of the first round of war in 1994. Many more have been abducted, harassed, imprisoned, and severely beatenwhich Politkovskaya herself knows from personal experience (briefly described in the book). She also has been the target of death threats that have caused her to flee Russia for a time. Nonetheless, she continues to travel to Chechnya and bring back accounts of a horrific waraccounts that we would otherwise not have.

Therefore, I propose the following hypothesis. This book represents a political position in a struggle where the stakes are exceedingly high. The author wants us to appreciate this because she hopes to enlist our support in her cause. Her cause is stopping a small but very cruel war and perhaps saving Russias nascent democracy.

Next page