Thomas Goltz

CHECHNYA DIARY

A WAR CORRESPONDENTS STORY OF SURVIVING THE WAR IN CHECHNYA

The observer affects the observed.

- ESSENCE OF THE HEISENBERG UNCERTAINTY PRINCIPLE

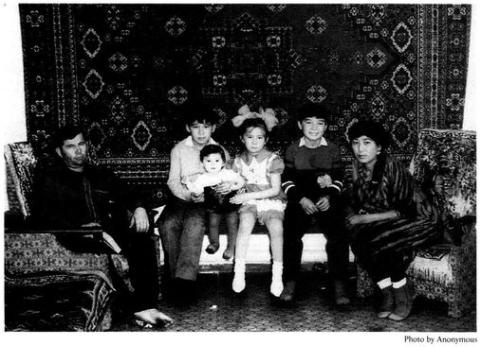

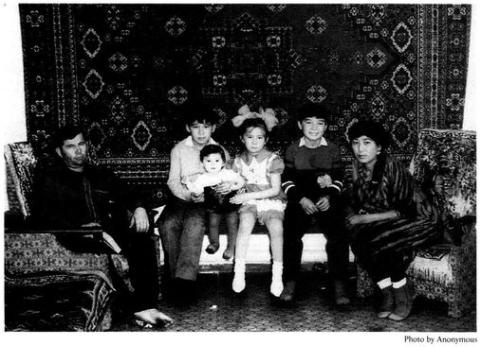

For Hussein and his family

prologue

WAR CORRESPONDENT ON A ROOF

It was while standing atop a two-story apartment block in a muddy little town in western Chechnya, waiting for an aerial assault to turn the mud into clay and the town into dust, that I started to reflect on the nature of my career, namely that of being a packager and purveyor of brutality between strange people in strange places, hopefully for the edification of television and reading audiences back home.

I was a war correspondent, and one, theoretically, in extreme danger. Aside from the minaret of the main mosque in town, the building I was standing on was the highest structure around. As such, it was an obvious target for the air attack expected to pummel the town that night. Because I was carrying a camera on a tripod with a shotgun microphone planted on topa rig that many say greatly resembles a recoilless rifle with telescopic sightthe potential for pilots and gunners mistaking me for a gunman was high. I would have shot at me, too, had I been a nervous Russian airman.

Four journalists had already been killed in Chechnya before my arrival in country. Three more were announced as missing and presumed dead during my stay. Two were from a St. Petersburg newspaper; I was the third. Over the course of the next two years of war, followed by two years of not-war-not-peace between Russia and Chechnya and then more years of renewed war that continue unabated down to the publication of this book, even more journalists would fallalthough their numbers would only be a drop in the bloody bucket of death and destruction visited upon players, both armed and unarmed, in that blighted land in the Russian North Caucasus.

Some people think that journalists involved in life-threatening work are brave. I no longer think so. If I ever get killed covering killing, I would like to state right now that the only person more foolish than me for getting into such a situation would be anyone who would describe my having done so as courageous. No, if I ever get killed covering killing, let my epitaph read something like He squandered the gift of life by trying to get too close to death.

As a print journalist I have lived dangerouslyand foolishlyjust to get the story, even when I knew said story would never see the light of day. The most ridiculous example of this tacit death urge was my hanging around the besieged city Sukhumi, in western Georgia, in 1993 with Georgian President Eduard Shevardnadze, long after it had become impossible to file reports on the collapsing situation. The reason for my silence was due to a lack of electricity and a functioning phone line. The media era of E-mail, the Internet, cell phones, and then, finally, direct video uplinks had not yet arrived.

Still, writer-recorders of war have it easy, relatively speaking. You dont have to see the shell hit the building to know that it connected; you can wait in the basement until the screaming has stopped. There you can huddle up with people who have been living like rats for weeks, and describe in great detail the odor of old urine and sweat and fear. You do not ask your subjects to step outside where the light is better for an interview about how they feel about it all.

That is what television journalists doand for the obvious reason that the image is all. You have to try and get as close as possible to the people shooting and the people getting shot, and make sure the lighting is right. And more. As a combat cameraman, you actually anticipate fighting and are often almost disappointed if it does not happen. What few admit but secretly hope for is that someone will actually die in front of your lens, because it makes such compelling material.

And that was exactly where I was that cold and frightening night, standing on a roof in an obscure little town in western Chechnya, risking my life in order to further my career by capturing an adequate measure of the death and destruction that was to be visited upon the very people I had been living with for several weeks, all for the story.

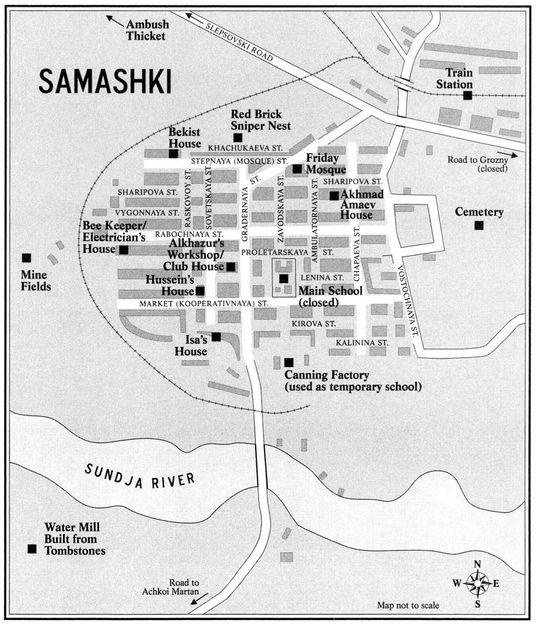

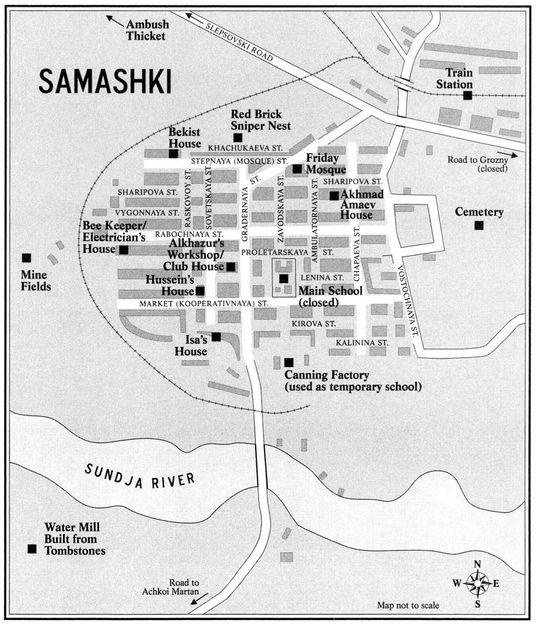

The place was called Samashki. In the Chechen language the name means the place of deer. It was destined to become the most resonant symbol of Russian brutality during the course of what most outsiders call the first Russo-Chechen War, when rampaging Russian forces slaughtered some two hundred men, women, and children in the town. Samashki maintained that status for almost five years, until its status as a font of sorrow was usurped by the nearby town of Alkhan Yurt, when the latter was subjected to an even more brutal wave of wanton killing during the second Russo-Chechen war.

Actually, most Chechens do not make any distinction between first and second wars. They tend to regard the entire period from the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 down to today as being a long continuum of cold, cool, warm, and hot conflict with Russia, often expressed as merely the most recent attempt by Russians, repeated approximately every 50 years, to eradicate the Chechens from the face of the earth.

Genocide, in a word.

I am not sure if I agree with that formulation, but it is what most Chechens believe. And given their communal experience over the past ten years, with over 100,000 civilians and combatants killed and virtually all survivors forced into refugee status or reduced to a troglodyte life in the shattered ruins of their cities and towns and villages, it is difficult to blame them for believing so. Or blame them for their slow slide toward an Al Qaeda-style of Islam, with all that that implies in our post-September 11 world.

I first entered Samashki in mid-February 1995, and discovered a place so nondescript that I had initial misgivings about staying there at all. My assigned task was to make a one-man television documentary for ABCs Nightline on the Chechen spirit, an on-camera exploration about what motivated the outgunned Chechens to continue resisting the might of the Russian army. Virtually all other foreign correspondents in Chechnya at the time were focusing their attention on the capital city, Grozny. But here I was, some thirty miles from the action, stuck in a large village consisting of walled compounds lining wandering lanes that seemed to be inches deep in mud, even when it did not rain. I stayed because I guess I intuited that the writing was on the wall. War would come to Samashki, and I would be there to greet it, camera in hand.

Situated on a small salient of territory still under the control of forces loyal to Chechen President Djohar Dudayev, Samashki controlled the main railway tracks to Grozny from the North and West. As such, it was an obvious target for the Russian forces as they slowly but surely cleansed the denuded hills of northern Chechnya of resistance, pushing ever southward toward the mountains where Dudayev had chosen to make his last stand.

My plan was to spend a few days in town, get to know some folks, go out on a few missions, and then get out before the place was obliterated. In the best of all possible worlds, I would accomplish the getting-out part while the obliteration was taking place. In the television trade, this is called collecting bang-bang.