Essential Histories

Russias Wars in Chechnya 19942009

Essential Histories

Russias Wars in Chechnya 19942009

Mark Galeotti

Contents

Introduction

A bullet, a bomb, or a missile cannot, will not, destroy us. This will not end. We will sooner or later revenge ourselves upon you for the deeds you have done to us.

Open letter from the Wolves of Islam movement to the people of Russia, 1995

Post-Soviet Russia fought its first war the First Chechen War in 199496. In effect, it lost: a nation with a population of 147 million was forced to recognize the effective autonomy of Chechnya, a country one-hundredth its size and with less than one-hundredth of its people. A mix of brilliant guerrilla warfare and ruthless terrorism was able to humble Russias decaying remnants of the Soviet war machine.

But this was a struggle that had already run for centuries. Russia licked its wounds and built up its forces for a rematch, invading again in 1999 and by 2009 declaring the Second Chechen War won. However, this did not mean peace in Chechnya, where a guerrilla movement still survives at the time of writing, much less in the wider North Caucasus region, which seems to have been infected by insurrection. It is also worth questioning just how much of a victory this really was for Moscow, given that its price has been installing Ramzan Kadyrov, an erratic warlord-turned-president who in many ways runs Chechnya as his own private kingdom, as well as having to provide massive amounts of federal funding to rebuild the country and buy off Kadyrov and his allies.

If only Boris Yeltsin, first president of post-Soviet Russia, had been more aware of his history. After all, it is hardly surprising that the first and most serious direct challenge to Moscows rule after the collapse of the USSR came from the Chechens. An ethnic group from the North Caucasus mountain region on Russias southern flank, the Chechens who call themselves Nokhchy or Vainakh have lived in the region for thousands of years, their land defined by the Sunja and Terek rivers to the north and the west, the Andi mountains to the east and the mighty Caucasus range to the south. Their reputation has been as a proud, fractious, raiding people. This is, after all, a land of mountains and valleys. Diagonal ranges cut the country from north-west to southeast, with the lowland valleys and hillsides in between often thickly forested. This is perfect bandit and guerrilla country, but also a geography that worked against the rise of any strong central power.

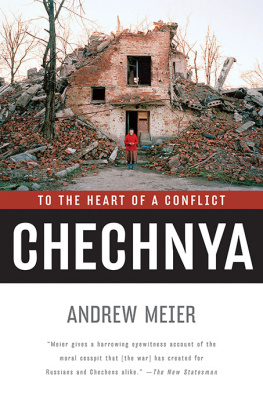

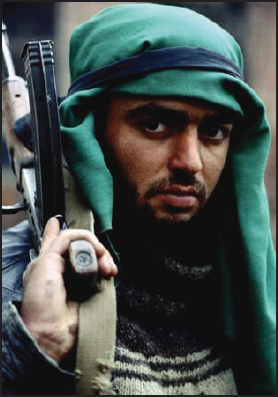

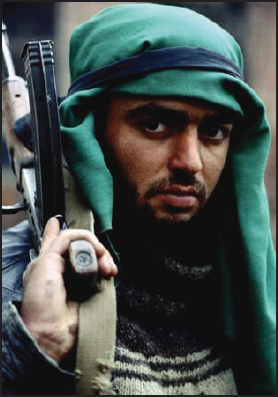

Grozny, 17 March 1995: a Chechen fighter pictured shortly after the Chechen capital had finally fallen. His AKM-47 is a dated but still effective weapon for the close-quarters fighting that had scarred the city. ( GRIGORY TAMBOULOV/Reuters/Corbis)

This 19th-century postcard of the Georgian Military Highway Russias main route through the Caucasus shows the contrast between fertile lowlands and rough, demanding highland relief which was such a problem for successive generations of foreign invaders and occupiers. (Library of Congress)

Instead, what emerged was a people divided but united, politically divided between clan (teip) and family, but with a shared culture characterized by a close-knit sense of community, based on tradition, kinship and a fierce sense of honour, which valued independence to an immense degree. The Russians came to realize this when their own imperial expansion brought them to the North Caucasus in the 18th century, their eyes fixed on other prizes: Georgia to the south, and beyond that, Safavid Iran and the Ottoman Empire. Of all the North Caucasian mountain peoples, the Chechens put up the fiercest resistance to the Tsarist Russian invaders of the 18th and 19th century and Soviet occupiers of the 20th. They would suffer the most for it, too, including massacres and forced deportations. Leaders such as Sheikh Mansur and, especially, Imam Shamil (ironically, an Avar from present-day Dagestan, not a Chechen) have become symbols of national pride and independence alongside modern-day figures such as former elected Chechen president and tactical genius Aslan Maskhadov, the man who masterminded the counter-attack that saw Russian forces pushed out of the Chechen capital, Grozny. A bandit tradition, of the so-called abreg or abrek a wronged man who strikes back against abusive lords, like a Robin Hood of the North Caucasus has metamorphosed into the cult of the guerrilla. A generation of Chechens is now reaching adulthood having known nothing but conflict and the messy, brutal counter-insurgency operations which followed the formal end of the war in 2009.

Meanwhile, the conflict proved pivotal in shaping post-Soviet Russia, too. The First Chechen War demonstrated the limits of the new democracy. Although Yeltsin had originally told the constituent republics and regions of the Russian Federation to take as much sovereignty as you can stomach, when the Chechens took him at his word, he proved too much of a nationalist to be willing to see his country break apart. It also undermined his credibility with the military and the country alike, forcing him to fall back on questionable political alliances and outright vote-rigging to hold on to power. On the other hand, the second war was the making of the hitherto-unknown prime minister and then president Vladimir Putin, allowing him to present himself as the saviour of Russian territorial integrity, the scourge of terrorists and kidnappers and the strong man able to succeed where Yeltsin had failed.

The Chechen wars of 199496 and 1999 2009 were dramatic, vicious and complex affairs, full of extremes of heroism, atrocity and unexpected reversals. An irregular guerrilla force proved able to drive a modern army out of Grozny, for example, when well motivated and brilliantly led. Conversely, the Russians demonstrated an impressive ability to learn from their mistakes when they subsequent created a Chechen force of their own, able to take the war to the rebels on their own terms. As such, the Chechen wars covered the whole spectrum of modern conflict, from a handful of relatively conventional clashes between regular units, through hard-fought urban battles to the bitter military and political campaigns of terrorism and counter-insurgency. In many ways they epitomize the new paradigm of war, as armies come to terms with warfare that is more often asymmetric and political, as much about winning hearts and minds or at least shattering the enemys will to fight as carrying the day on the battlefield.

Chronology

| 1585 | Ottoman Empire claims control over Chechnya. |

| 172223 | Russo-Persian War pits Safavid Iran against Peter the Greats Russia. |

| 1783 | Treaty of Georgievsk implicitly cedes North Caucasus to Russian Empire. |

| 1784 | Sheikh Mansur leads first rebellion against Russians. |

| 1785 | Russian defeat at the battle of the Sunja River. |

| 181764 | Caucasus War. |

| 1818 | Russians found fort of Groznaya; later becomes city of Grozny. |

| 183459 | Imam Shamils revolt against the Russians. |

| 1859 |

Next page