CONTENTS

GLOSSARY OF ACRONYMS USED IN THIS TEXT:

| GRU | Glavnoye razvedyvatelnoye upravleniye Main Intelligence Directorate |

| GSh | Generalny shtab General Staff |

| KSO | Komanda spetsialnykh operatsii Special Operations Command |

| MChS | Ministerstvo po chrezvychainym situatsiyam Ministry for Emergency Situations |

| MO | Ministerstvo oborony Ministry of Defense |

| MP | Morskaya pekhota Naval Infantry |

| SV | Sukhoputnye voiska Ground Forces |

| TsVO | Tsentralny voyenny okrug Central Military District |

| VDV | Vozdushno-desantniye voiska Air Assault Troops |

| VO | Voyenny okrug Military District |

| VP | Voyennaya politsiya Military Police |

| VS | Voyenniye sily Armed Forces |

| VVO | Vostochny voyenny okrug Eastern Military District |

| YuVO | Yuzhny voyenny okrug Southern Military District |

| ZVO | Zapadny voyenny okrug Western Military District |

INTRODUCTION

In the late 19th century, Tsar Alexander III is famously supposed to have remarked that Russia has only two allies: its army and its navy. If that is true, then since its emergence from the dissolution of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991, modern Russia has been singularly exposed. After all, it inherited from the USSR a portion of an army that was not only in serious decline, beset by problems of indiscipline, demoralization, backwardness and decay, but also designed for the kind of war a full-scale confrontation with NATO that the new regime could not envisage ever fighting. Meanwhile, Moscow lacked the money, the political will, and even the vision to be able to reform this disintegrating relic.

The result was disastrous, not least during the First Chechen War (199496), when the Army used brutal and heavy-handed tactics that led to massive civilian casualties, yet was still, in effect, defeated by a smaller but more disciplined and imaginative rebel force. The 1990s were a time of chaos and redefinition across Russia, and nowhere more so than within the military. In 1993, in defiance of the constitution, President Boris Yeltsin used the Army to shell his unruly parliament in Moscow's White House into submission. Officers who dared to criticize the Kremlin were dismissed; soldiers moonlighted as mafia hitmen; deserters terrorized remote communities; and officers embezzled as much as they could, while forced to live in unheated tank sheds and condemned apartment buildings.

Yet for all that, there were faithful torchbearers within the once-proud military who did not forget the professionalism and discipline of past times, while both the geopolitical challenges facing Russia and its rich martial mythology energized those within the leadership who were eager to see a revival of their countrys military strength. The rise to power of Vladimir Putin at the end of 1999, coinciding with a recovery of the Russian economy, at last permitted the start of a process of long-term rearmament and reform.

The Russian Army of today is increasingly aware of the value of modern battlefield medicine, not least because its professional soldiers are more valuable than the cannon-fodder conscripts of old. This senior lieutenant (note rank stars on his epaulet) from the Military Medical Service is in full combat gear, with low-visibility badges on his uniform and a slung AK-74M assault rifle. (Russian Ministry of Defense)

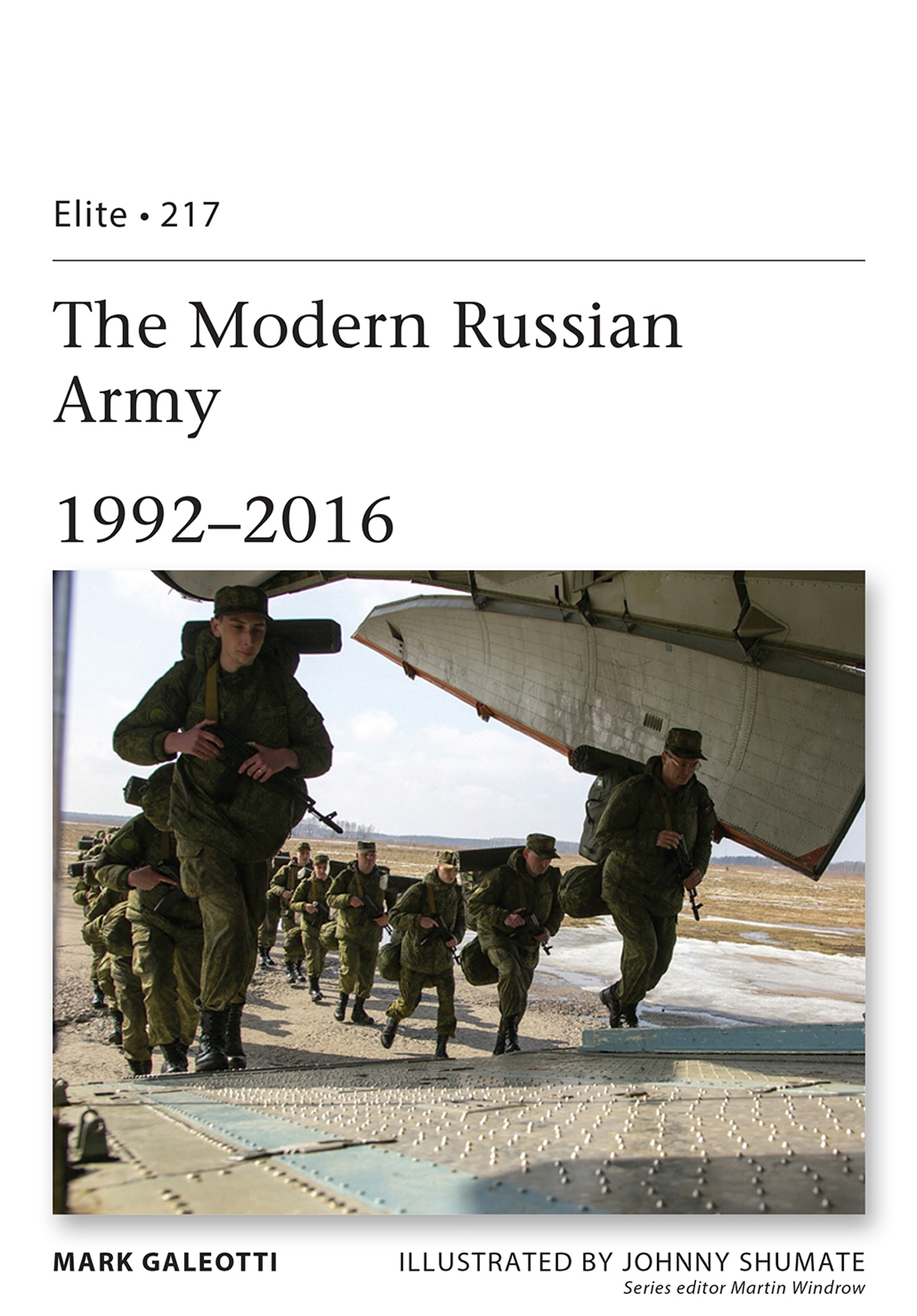

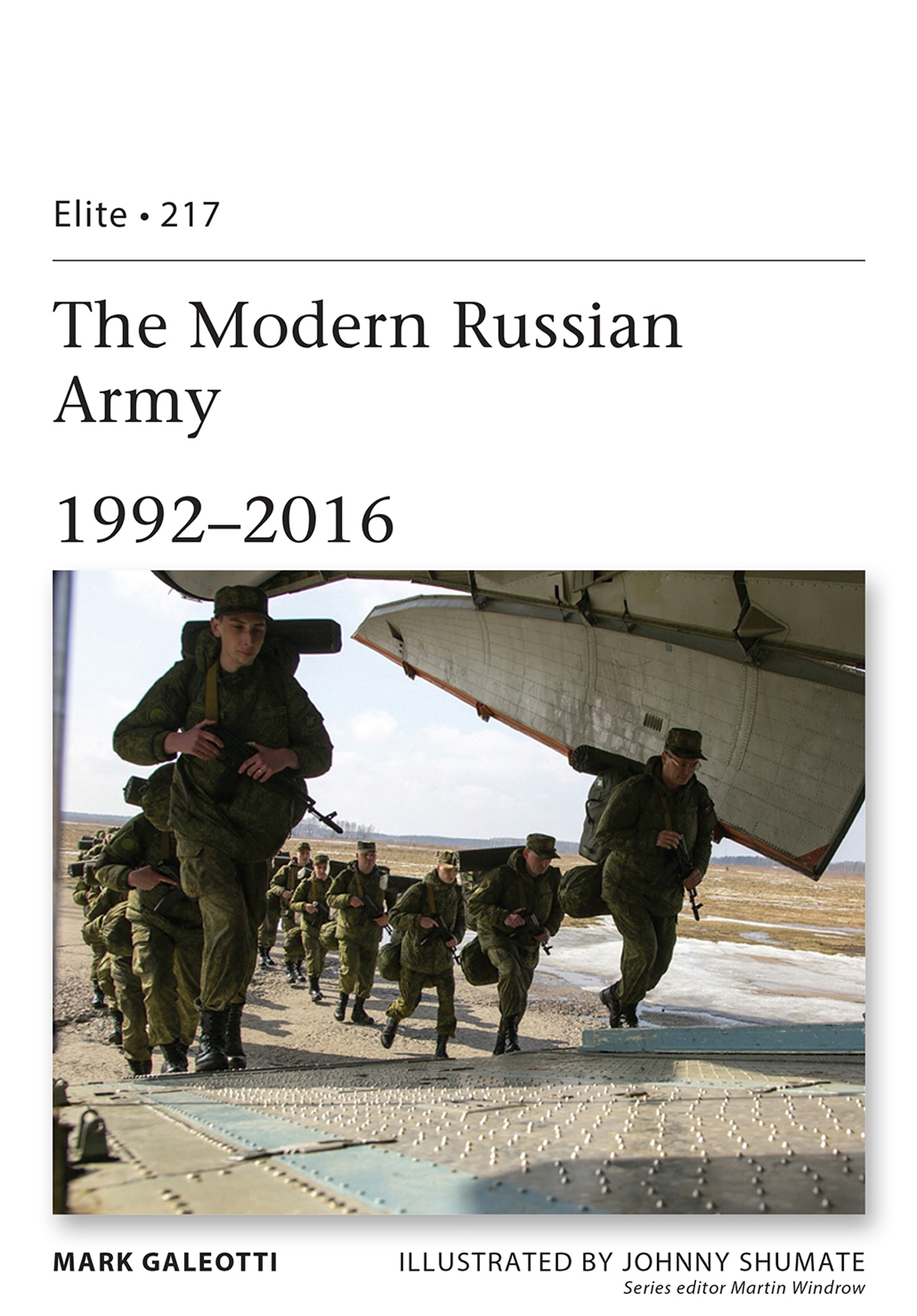

Since the early 1990s Russias new army has undergone a turbulent transformation, from the scattered leftovers of a decaying and partitioned Soviet military into the disciplined forces that seized Crimea virtually overnight in 2014. In the space of 25 years they have fought two wars in Chechnya, one in Georgia and another in Ukraine. They have battled insurgents in Tajikistan and Syria, sheltered rebellious clients in Moldova, and contributed to multinational peace-keeping operations in the Balkans. Their modernization programs are still a work in progress, but they are spending 4.5 percent of their GDP on the military (as of 2014), making Russia the third-ranking nation in global defense spending behind only the USA and China. This is a process that may yet become stalled by the countrys current economic problems linked to the massive fall in world oil prices; nevertheless, for the moment and the foreseeable future, it ensures that Russia is still the pre-eminent Eurasian military power, with the capacity not only to defend the Motherland but also to project the Kremlins interests well beyond its borders.

A Russian-supplied BMP-2 infantry fighting vehicle in Syria, where its 30mm autocannon makes it especially effective in urban combat. The deployment of aircraft and ground troops into Syria in 2015 represented a distinctly new phase in Russian power projection. (Russian Ministry of Defense)

BORN IN CRISIS

The collapse and partition of the USSR was a traumatic experience for the Soviet military, which was already embroiled in local ethnic conflicts and coping with problematic withdrawals from Central Europe. Even while the Soviet Union still stood it had already begun its painful retreat from empire. The Warsaw Pact ostensibly a military alliance, but in reality the fiction that allowed Moscow to base troops in and control its Eastern European satellites had become increasingly untenable. Many of these countries were restive, and Moscow could no longer afford the economic, political and military cost of keeping them under its thumb. On December 7, 1988, in a momentous speech to the United Nations, Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev announced that he would start drawing down troop deployments in Eastern Europe.

Protesters in central Moscow present the crew of a T-72 tank with flowers during the August 1991 coup attempt. Ultimately, the unwillingness of the military to back the conservative plotters doomed their ill-planned adventure. (Ivan Simochkin)

What was intended to be a phased and partial withdrawal soon became overtaken by events, as Communist governments across the region started to fall in 198990. In Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Bulgaria new governments were elected; the DDR (East Germany) effectively collapsed; and a violent uprising saw Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu toppled and executed. On February 25, 1991 the Warsaw Pact was formally disbanded. This left half-a-million Soviet troops (and 150,000 dependents) stranded in countries technically no longer under their control, nor even especially friendly. This forced an accelerated withdrawal, often before there were barracks or bases ready to accommodate them. While what was then still West Germany helped pay for the removal of Soviet troops from the DDR a process that would take until 1994 elsewhere the situation was less orderly. The USSR simply had nowhere to put its returning legions: as of July 1990, 280,000 military families were reportedly without housing.