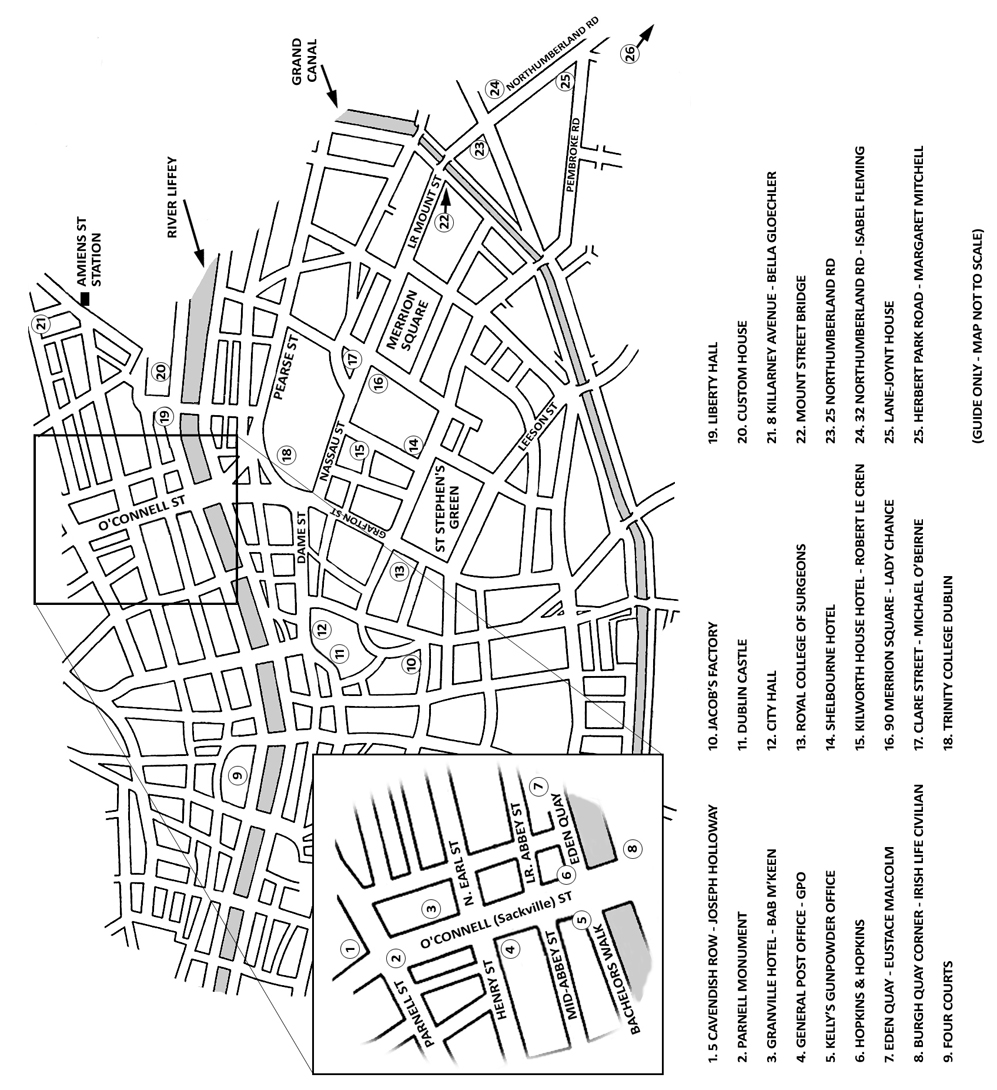

Apart from some small actions, the 1916 Rising lasted seven days, from Easter Monday to the following Sunday.

Easter Monday, 24 April 1916:

Beginning of rebellion. Main body of rebels muster outside Liberty Hall conflicting orders result in a turnout much smaller than hoped for. From about midday on, the following locations are occupied by rebels:

GPO and other buildings in OConnell Street area;

Four Courts, Mendicity Institution;

St Stephens Green, College of Surgeons;

Bolands Mills and surrounding area, including Mount Street Bridge and nearby houses;

City Hall and several buildings overlooking Dublin Castle;

Jacobs biscuit factory, Davys pub by Portobello Bridge;

South Dublin Union and Jamess Street area;

Magazine Fort in Phoenix Park.

Proclamation of Republic read by Pearse outside GPO. Lancers charge down OConnell Street. Looting starts. That afternoon the British counterattacks begin.

Tuesday, 25 April 1916:

City Hall retaken by military. Shelbourne Hotel occupied by soldiers and machine-gun fire forces rebels to retreat from St Stephens Green to the College of Surgeons. British reinforcements, including artillery, arrive. Martial Law proclaimed.

Wednesday, 26 April 1916:

Liberty Hall shelled by Helga, backed by field guns. Artillery put into action against buildings on OConnell Street. Kellys Fort evacuated. Metropole Hotel occupied by rebels. Troops marching from Dun Laoghaire halted by rebels at Mount Street Bridge. After many hours of intense fighting and terrible casualties, the military gain control of the area. Clanwilliam House burns to the ground. Mendicity Institution retaken by the British.

Thursday, 27 April 1916:

Military shelling of OConnell Street intensifies. Fires on OConnell Street begin to rage out of control. Hopkins & Hopkins and Imperial Hotel evacuated because of the inferno.

Friday, 28 April 1916:

General Sir John Maxwell arrives in Dublin. Metropole Hotel evacuated. Rebels evacuate GPO. New HQ established in Moore Street.

Saturday, 29 April 1916:

Non-combatants murdered in North King Street. Rebel leaders in Moore Street decide to surrender. Four Courts garrison surrenders.

Sunday, 30 April 1916:

Rebels in remaining outposts surrender College of Surgeons, Bolands, Jacobs and the South Dublin Union. Deportation of prisoners.

Wednesday, 3 May Friday, 12 May:

Fifteen rebels, including the seven signatories of the Proclamation of the Republic, are executed by firing squad.

PREVENTION OF EPIDEMIC

Persons discovering dead bodies should inform the Police or the Chief Medical Officer of Health, Municipal Buildings, Castle Street, immediately.

When wars and conflicts are studied, the usual method is to divide the participants into friend and enemy, us and them; and in the case of Ireland, the rebels and the British. But sometimes the more interesting division is into combatants and non-combatants, armed and unarmed those who were doing the actual fighting and those who were just caught up in it.

When the rebellion of 1916 had ended, more than 400 people were dead and over 2,000 wounded. More than half of these were civilians, and while it could be argued that the casualties among the rebels were in control of their own destiny and that those on the side of the authorities were at least doing their duty, the stark fact is that the destiny of the civilian casualties was out of their hands. They were in their homes or travelling to work or shopping. Some, of course, were simply fatally curious.

Many books have been written on the history of the Rising who did what, where it was done, why they did it, what the outcome was. While these usually address the civilians predicament to some degree, in general they are written from a factual point of view how many were killed, who the looters were, etc. Apart from the effect the rebellion had on the unfortunate civilian casualties, few, if any, histories examine what effect it had on the general population.

In recent years the Bureau of Military History has made many hundreds of witness statements relating to the Rising freely available on the Internet. However, while these histories are important, and indeed fascinating, they are largely confined to participants and concern military history. So, are there statements from civilian eyewitnesses about the week of rebellion in 1916?

Thankfully the answer is yes, although not in as official a capacity as the Bureau of Military Historys collection. Many people at the time had an acute awareness of the fact that history was being made before their eyes and that present and future generations would want to know about it. So they wrote diaries or sent letters, some of which still survive. Some witnesses wrote memoirs or an autobiography in later years and included a chapter on the Rising and how it affected them. In other cases, newspaper or magazine editors with an eye for the human story published contributions from civilians who were directly affected.

![Lorcan Collins [Lorcan Collins] - 1916: The Rising Handbook](/uploads/posts/book/143326/thumbs/lorcan-collins-lorcan-collins-1916-the-rising.jpg)

www.mercierpress.ie

www.mercierpress.ie http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher

http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press

http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press