Also by Maggie OFarrell

After Youd Gone

My Lovers Lover

The Distance Between Us

The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox

The Hand That First Held Mine

Instructions for a Heatwave

This Must Be the Place

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF AND ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA

Copyright 2017 by Maggie OFarrell

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Tinder Press, an imprint of Headline Publishing Group, a Hachette UK Company, London, in 2017.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Knopf Canada and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House Canada Limited.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: OFarrell, Maggie, 1972author.

Title: I am, I am, I am : seventeen brushes with death / Maggie OFarrell.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2018.

Identifies: LCCN 2017028597 (print) | LCCN 2017037164 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525520221 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525520238 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : OFarrell, Maggie, 1972 | Novelists, Irish20th centuryBiography.

Classification: LCC PR 6065. F 36 (ebook) | LCC PR 6065. F 36 Z 46 2018 (print) | DDC 823/.914 [ B ]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017028597

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication data is available upon request

ISBN 978-0-7352-7411-2 | eBook ISBN 978-0-7352-7412-9

Ebook ISBN9780525520238

Cover illustration by Gina Triplett

Cover design by Kelly Blair

v5.1

ep

for my children

In some cases, names, appearances and locations have been changed to protect the identities of those who may not have wanted to be written about in a book.

Certain sections of this book originally appeared, in other forms, in the following publications:

parts of Daughter, in Guardian Weekend, May 2016

parts of Baby and Bloodstream, in Good Housekeeping, February 2007

parts of Abdomen, in the Guardian, May 2004

I took a deep breath and listened to the old

brag of my heart. I am, I am, I am.

Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar

Contents

On the path ahead, stepping out from behind a boulder, a man appears.

We are, he and I, on the far side of a dark tarn that lies hidden in the bowl-curved summit of this mountain. The sky is a milky blue above us; no vegetation grows this far up so it is just me and him, the stones and the still black water. He straddles the narrow track with both booted feet and he smiles.

I realise several things. That I passed him earlier, farther down the glen. We greeted each other, in the amiable yet brief manner of those on a country walk. That, on this remote stretch of path, there is no one near enough to hear me call. That he has been waiting for me: he has planned this whole thing, carefully, meticulously, and I have walked into his trap.

I see all this, in an instant.

This daya day on which I nearly diebegan early for me, just after dawn, my alarm clock leaping into a rattling dance beside the bed. I had to pull on my uniform, leave the caravan and tiptoe down some stone steps into a deserted kitchen, where I flicked on the ovens, the coffee machines, the toasters, where I sliced five large loaves of bread, filled the kettles, folded forty paper napkins into open-petalled orchids.

I have just turned eighteen, and I have pulled off an escape. From everything: home, school, parents, exams, the waiting for results. I have found a job, far away from everyone I know, in what is advertised as a holistic, alternative retreat at the base of a mountain.

I serve breakfast, I clear away breakfast, I wipe tables, I remind guests to leave their keys. I go into the rooms, I make the beds, I change the sheets, I tidy. I pick up clothes and towels and books and shoes and essential oils and meditation mats from the floor. I learn, from the narratives inherent in possessions left strewn around the bedrooms, that people are not always what they seem. The rather sententious, exacting man who insists on a specific table, certain soap, an entirely fat-free milk has a penchant for cloud-soft cashmere socks and exuberantly patterned silk underwear. The woman who sits at dinner with her precisely buttoned blouse and lowered eyelids and growing-out perm has a nocturnal avatar who will don S&M outfits of an equestrian bent: human bridles, tiny leather saddles, a slender but vicious silver whip. The couple from London, who seem wonderingly, enviably perfectthey hold manicured hands over dinner, they take laughing walks at dusk, they show me photos of their weddinghave a room steeped in sadness, in hope, in grief. Ovulation kits clutter their bathroom shelves. Fertility drugs are stacked on their nightstands. These I dont touch, as if to impart the message, I didnt see this, I am not aware, I know nothing.

All morning, I sift and organise and ease the lives of others. I clear away human traces, erasing all evidence that they have eaten, slept, made love, argued, washed, worn clothes, read newspapers, shed hair and skin and bristle and blood and toenails. I dust, I walk the corridors, trailing the vacuum cleaner behind me on a long leash. Then, around lunchtime, if Im lucky, I have four hours before the evening shift to do whatever I want.

So I have walked up to the lake, as I often do during my time off, and today, for some reason, I have decided to take the path right around to the other side. Why? I forget. Maybe I finished my tasks earlier that day, maybe the guests had been less untidy than usual and Id got out of the guesthouse before time. Maybe the clear, sun-bright weather has lured me from my usual path.

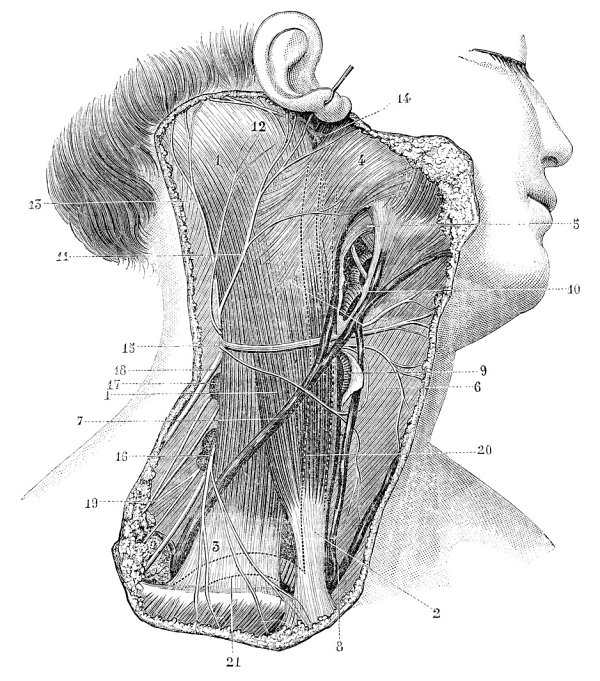

I have also had no reason, at this point in my life, to distrust the countryside. I have been to self-defence lessons, held at the community centre in the small Scottish seaside town where I spent my teens. The teacher, a barrel-shaped man in a judo suit, would put scenarios to us with startling Gothic relish. Late at night and youre coming out of a pub, he would say, eyeing us one by one from beneath his excessively sprouting eyebrows, and a huge bloke lunges out from an alleyway and grabs you. Or: youre in a narrow corridor in a nightclub and some drunk shoves you up against a wall. Or: its dark, its foggy, youre waiting at the traffic lights and someone seizes your bag strap and pushes you to the ground. These narratives of peril always ended with the same question, put to us with slightly gloating rhetoric: so, what do you do?

We practised reversing our elbows into the throats of our imaginary assailants, rolling our eyes as we did so because we were, after all, teenage girls. We took it in turns to rehearse the loudest shout we could. We repeated, dutifully, dully, the weak points in a male body: eye, nose, throat, groin, knee. We believed we had it covered, that we could take on the lurking stranger, the drunk assailant, the bag-snatching mugger. We were sure wed be able to break their grip, bring up our knee, scratch at their eyes with our nails; we reckoned we could find an exit out of these alarming yet oddly thrilling synopses. We were taught to make noise, to attract attention, to yell, POLICE. We also, I think, imbibed a clear message. Alleyway, nightclub, pub, bus-stop, traffic lights: the danger was urban. In the country, or in rural towns like ourswhere there were no nightclubs, no alleyways and no traffic lights, eventhings like this did not happen. We were free to do as we pleased.