W. W. N ORTON & C OMPANY

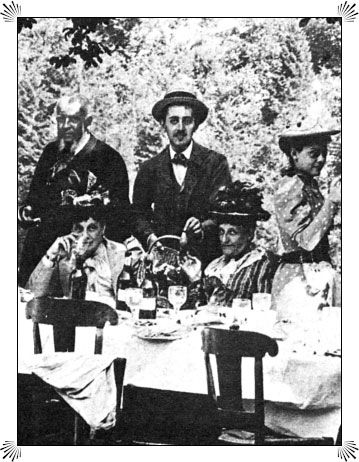

Page proof with Prousts corrections for Du Ct de chez Swann courtesy of Bibliothque nationale de France. Frontispiece photograph courtesy of Mante-Proust Collection.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Shattuck, Roger.

Prousts way: a field guide to In search of lost time / by Roger Shattuck.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references

ISBN: 978-0-393-07870-1

1. Proust, Marcel, 18711922. A la recherche du temps perdu. I. Title.

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 10 Coptic Street, London WC1A 1PU

H. Francis Shattuck, Jr.

A SENSE OF LIFE

T wo impulses propel this bookone affirmative and one corrective.

Each chapter affirms different ways in which Prousts superficially forbidding novel In Search of Lost Time welcomes us to a world of vivid places and intensely human characters. And those chapters taken together affirm the philosophical and moral profundity of the book, kept in motion by a narrative structure as simple and as sturdy as that of a suspension bridge. Perhaps I shall win a few readers to my conviction that the Search is the greatest and most rewarding novel of the twentieth century, outdistancing its closest rivals, Joyces Ulysses, Thomas Manns The Magic Mountain, and Faulkners Absalom, Absalom! But no literary sweepstakes will be mounted here. I undertake an exploration of the bounty of literature in all its forms.

The corrective impulse that also carries this book appears primarily in Chapters V and VI and addresses two misapprehensions firmly lodged in prevailing opinion about Proust and his work.

First, even though the seven volumes of the Search deal with motifs of time, the past, and recollection, the novel is not primarily about memory and sentiments concerning the past. The famous episode of the madeleine cake and the cup of tea introduces a series of reminiscences to which Marcel, the protagonist, attaches great significance. But the reminiscences provide stepping-stones on a path that will lead beyond their uncertainty to more essential and more durable mental states. Marcel finally outgrows involuntary memory in a way that allows him, against all odds and expectations, to find himself and his vocation.

The second corrective turns to another stereotype applied to Proust by popular journalists and cartoonists and even by scholars. They portray him as the ultimate aesthete, the impeccably barbered and tailored dandy reclining on a chaise lounge, sipping a cup of tea, and closing his heavily lidded eyes in exaltation. One is meant to glimpse, symbolically arrayed behind him, the founders and devotees of this tradition of artistic refinement: the philosophers Shaftesbury and Kant; the Romantic poets Schiller, Coleridge, Gautier, and Poe, who enunciated the doctrine of art for arts sake; the great figures of Flaubert and Baudelaire, who linked art for arts sake to a darker realism; the French schools of Symbolism and Decadence; and the associated Anglo-Irish branch of Ruskin, Pater, Wilde, Yeats, and Joyce. Posed as the culmination of this two-century aesthetic heritage, Proust has become something of a cult figure.

The nearly identical titles of two intelligent critical works on Proust reveal how far scholars can go toward accepting the aesthetic interpretation of Prousts work. Barbara Bucknall entitled her study The Religion of Art in Proust (1969). Leon Chai entitled his book Aestheticism: The Religion of Art in Post-Romantic Literature (1990) and devoted the crowning chapter to Proust. These two books, like the popular caricature of Proust as decadent dandy, combine sound insights with lingering elements of distortion. In Chapter VI, I try to adjust our understanding of Proust as an artist more closely to the evidence than is the case with the stereotype of the ultimate aesthete. The protagonist of the Search does not retreat to a monastery devoted to the religion of art. He returns to society in a last attempt to test the integrity of his literary calling. This time, he finds his way. The novel does not subside into passivity and coterie art, as does the decadent hero, Des Esseintes, in Huysmans A rebours ( Against Nature, 1884). The Search creates a four-dimensional society and a stringently critical perspective on the snobbery and superficiality of that society. Proust was more a social critic than a decadent.

Reading Proust bears many resemblances to visiting a zoo. The specimens he collected from the remotest corners of society amaze and amuse us in their variety. Their extremes of color and shape, size and locomotion, temperament and response also cause a certain apprehension. And before long we realize that this is no ordinary zoo, where the creatures exhibited are confined in cages. The tables have been turned on us. The specimens roam free in a vast park. We drive through it confined to our vehicles, scorned by some animals, pursued and harassed by others. Ours is the alien presence, at least until we have remained long enough to adapt to the environment and to provoke no stir. Then we may begin to wonder why anyone set out to create this vast narrative landscape, and how we were ever induced to enter a zoological territory so challenging.

Now that I have lived with In Search of Lost Time for several decades, I believe I can offer an answer to both questions. The novel opens (like the Tanach or Old Testament and Alice in Wonderland ) with a falla mental collapse backward and downward in time and space, an initial rite of passage, which carries the unidentified narrating consciousness to a critical point of near annihilation. We come to this sentence on the third page: I had only, and in its simplest form, the feeling of existence, as it must flutter in the deepest recess of an animal (I 5/i 4). All history and part of evolution have disappeared. The story almost sputters out at the startand then catches again with increasing force, which plunges us headlong into places and people and their actions.

What draws us to a zoo is the sheer sense of life, both shared and utterly alien, animating those beautiful and grotesque animals. The melodramatic fact of their existence makes us newly attentive to our own. Similarly, the amazing caricatures of human beings that roam the open zoo of Prousts novelAunt Lonie, the servant Franoise, the glowering Baron de Charlusreawaken us to our own existence. Marcel, the boy who grows to manhood in these pages, spends the early part of his life absorbed in his own sensations, which give him a powerful sense of life concentrated upon himself. Nothing is more precious than this physical, organic, inward sense of his own existence as himself in the worlds zoo. Yet, after every move to an unfamiliar place and a new bedroom, Marcel must build this sense of himself all over again. At the same time, he yearns to escape from the caul of this confined, self-absorbed existence and to reach out to other human creatures. He wants to know and to touch what is not part of him. He yearns to live beyond himself.