THE DEBS OF

BLETCHLEY PARK

and Other Stories

Roma Davies lives in Bower Mount Road, to the west of Maidstone. Its one of those spacious tree-lined streets of elegant Edwardian villas that the estate agents like to call desirable. Roma has lived here for most of her life, ever since she and Mike finally got married.

They met at the end of the war. Hed been on the Arctic convoys taking food and equipment to Russia, sailing around the north of Norway to Archangel. They lost sixteen Royal Navy ships and eighty-five merchant vessels to the U-boats. God knows how many men. If you went into the sea it was so cold you were dead within minutes. Roma was in the navy herself back then, a member of the Womens Royal Naval Service, known to all and sundry as the Wrens.

Mike and I wanted to get married but we didnt for ages because his mother said no. Roma laughs. We were ruled by our parents. Its extraordinary to think of it now. Ive never been able to be the boss. My daughters say, You must be joking, Mum! But I never was the boss.

When she left the Wrens, she wanted to work in horticulture. She loves plants. Her father didnt think that was a proper job for a young woman and sent her on a Pitmans secretarial course. Working as a typist was the sensible thing to do; it would bring in money straightaway. So Roma got a job at the Alliance Building Society offices on Londons Park Lane.

When she and Mike did eventually get married in 1951, they moved into a rented cottage at the southern end of Bower Mount Road. When their first daughter was two, with Mike working as an engineer on reasonably good money, they bought one of those elegant Edwardian villas with large bay windows, beautiful arched porches and the longest garden you could ever imagine. It was to be Romas home for more than fifty years.

It was a lovely house: lovely big garden; lots of happy memories; lots of friends. Sadly, theyre all dying off now.

Mikes heart gave way in 1996 and after Romas second stroke, her daughters persuaded her she couldnt live on her own. She moved into the Grove, another of those Edwardian houses that line Bower Mount Road, and even more spacious than Romas house. The Grove is a residential home for the elderly.

Roma sits in a tall-backed armchair in her room. Its about the size of a small hotel suite. There are photographs of her family, a few small pieces of furniture, and some paintings and ornaments she brought from her old home. They include two beautiful Royal Doulton figurines and a pretty watercolour of her grandmothers old house that reminds Roma of her childhood. She smiles a lot. She seems happy and the people at the Grove are kind and caring. A chirpy, friendly carer pops in to bring her tea and a piece of cake. Its someones birthday. The two women laugh at a misunderstanding over the sugar, comfortable in each others company. Roma is definitely happy here, you can tell. Shes smiling a lot, and laughing.

Even so. The Grove might be in Bower Mount Road, but it isnt Romas home. Not her real home. Not that the old house she and Mike lived in is hers any more it was sold to pay for her care. Its someone elses now, to do with as they please. For a brief moment, the smile disappears.

Theyve completely destroyed my front garden. The house was built in 1906. Its more than a hundred years old. There were all sorts of treasures in that garden, a hundred years of treasures, and theyve just ripped them out and made a huge car park.

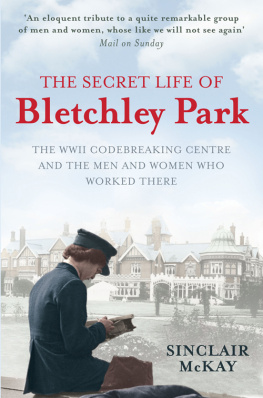

The smile, though, is never far away. Theres a photograph of a pretty young woman in Wrens uniform. Shes standing outside an old country house, smiling at the camera, a very pretty smile. Her hands are clasped contentedly in front of her. She looks happy... and very proud.

I was determined to be a Wren from when I was at school. I couldnt wait to get into the Wrens. I wanted to do my bit. We were brought up to be patriotic.

Romas family lived in Leigh-on-Sea, Essex, before the war. Romas mother loved being by the sea, as did Roma. In the summer, she and her brother would rush out of school at lunchtime and take a taxi down to the beach to have a picnic with their mother before taking another taxi back to school. But in the summer of 1939, everybody knew there was going to be a war with Hitlers Germany. Romas father thought the Thames Estuary would be the first place to be bombed, so he packed the entire family off to Devon.

Three days before war broke out we moved down to my great-aunts in Exeter. There was my brother, my sisters, my grandmother, two aunts and their children. It was a huge house, but we soon filled it up. She laughs again and then the smile is back, the same pretty smile in the photograph. I was very sheltered. It wasnt until we went down into town that I even realised we were at war.

As soon as she was seventeen, Roma rushed down to the local WRNS recruiting office to sign up, returning dejected to school after being told that seventeen wasnt old enough. You had to be seventeen and a half.

Six months later, Roma was a Wren. She trained at Mill Hill in north London, expecting to be posted somewhere by the sea, but to her disappointment she was sent just a few miles down the road to a new base at Eastcote where everything was secret. She was working with a lot of other Wrens on weird machines, with no real idea of what any of them were doing, or why. Except everything they did had to be done very quickly. Lives depended on it, so they did precisely what they were told.

I had no idea of the overall picture and no notion of what my friends were doing, she recalls.

When they had days off, they took the Tube into London and had fun, or simply something to eat that was different from navy rations.

We were often treated because we were in uniform. The manager of a cinema would say: Oh, let them in. Wed go to the Variety Club, and see comedians, dancers and singers decent ones. Wed eat in Lyons Corner Houses, nothing special, baked beans on toast, that sort of thing. We were paid the princely sum of nine shillings [45p] a week. We had quite a few meals each week on that nine shillings. Incredible really how we made it last.

After a few months, they told Roma they had a new job for her, somewhere north of London. Shed be living in much more comfortable conditions, in an old country mansion, and shed be working at somewhere very, very secret, even more secret than Eastcote. Roma was to be one of the thousands of young women who spent their war carrying out work vital to the war effort, but never able to confide in anyone about it.

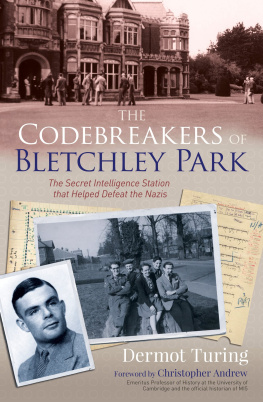

She would be working at Bletchley Park.

1

Phoebe Senyard was not very happy. She was packing up all the office files and equipment into tea chests. Phoebe had only just returned from a holiday with her mother to be told she was being sent to the War Station at Bletchley Park the very next day. She and Commander Crawford were to be the entire German naval codebreaking section. They werent the only ones going, of course, but the Navy had insisted that the Government Code and Cypher Schools real German Naval Section must stay in London, sat in the Admiralty, so she and Commander Crawford were going to be the only German naval experts at Bletchley. Phoebe was no codebreaker and she certainly wouldnt regard herself as a German expert. She didnt understand how anyone would. Shed originally been recruited as a clerk and knew very little about the German Enigma codes. Not that anyone else seemed to understand them either.

It was August 1939. Everybody knew that a war with Hitler was just around the corner. But no one had done much about the German codes. Admiral Sir Hugh Sinclair, who as chief of the secret service was in charge of the spies and the codebreakers, didnt believe the German codes would be broken. They were too modern, too complex. Ciphers produced by a machine, not by people. How could you break them without the machine? Commander Alastair Denniston, the head of the Government Code and Cypher School, agreed with the admiral. He usually did. Only Dilly Knox seemed to believe that Enigma could be broken. Phoebe was in no position to say whether the admiral or Mr Knox was right. Shed been picked out as one of the clerical workers who might be capable of doing a bit more, and once a week or so, if she was up to date with her own work, she helped Miss Yeoman register the naval Enigma messages. But there was very little else that anyone could do with them other than note down the main details, put them in the right order and then stack them away in a filing cabinet. No one thought there would ever be a chance of breaking them. Not even Mr Knox, and he was the Enigma expert. They were far too complex, even more complex than the German army and air force Enigma messages. Well, thats what Sheila Yeoman said.