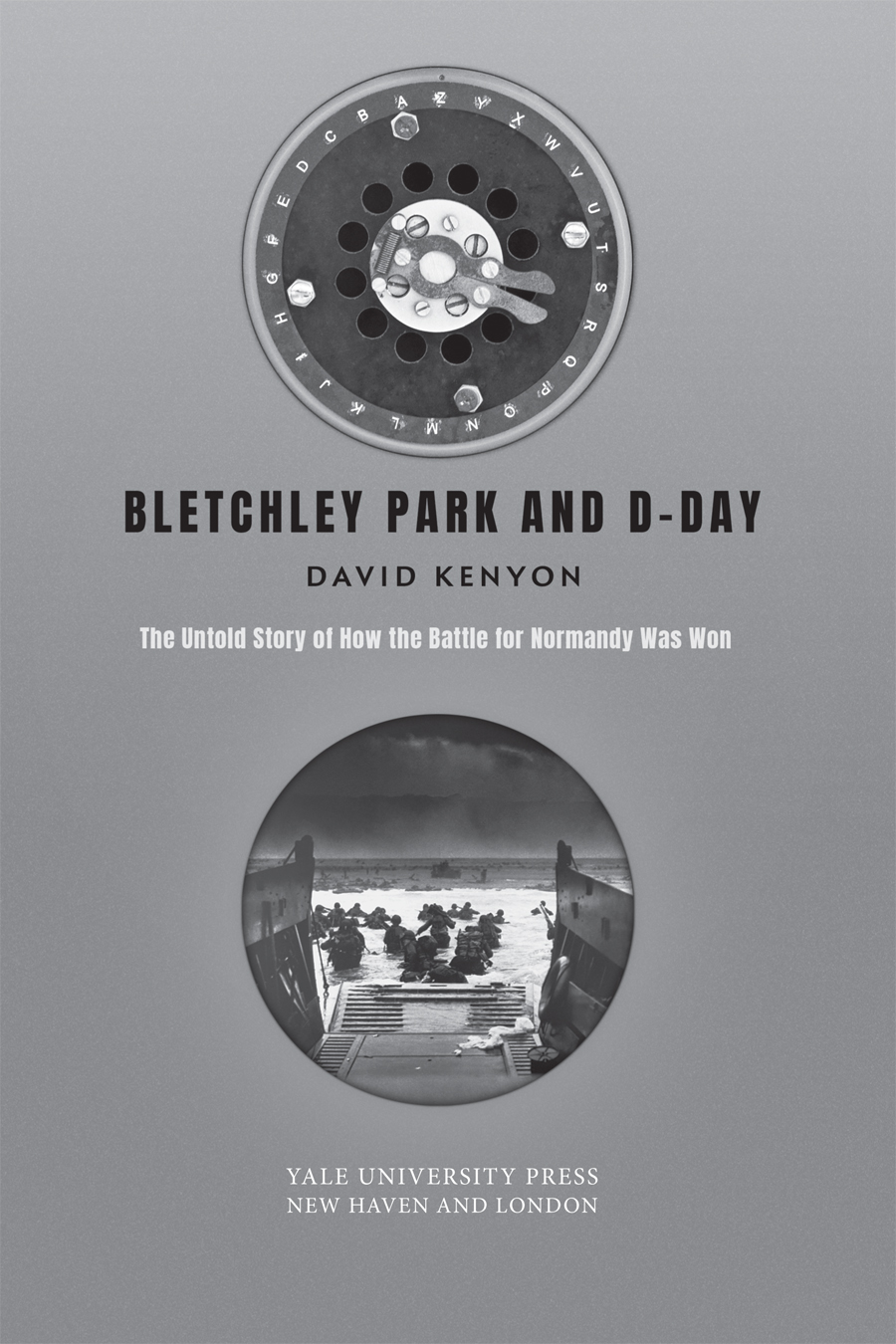

BLETCHLEY PARK AND D-DAY

Copyright 2019 David Kenyon

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Minion Pro Regular by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019938490

ISBN 978-0-300-24357-4

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The king hath note of all that they intend,

By interception which they dream not of.

Shakespeare, Henry V, Act II, Scene 2

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

ROBERT HANNIGAN

Former Director of the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) Cheltenham and Trustee of Bletchley Park

T he enduring memory of D-Day is one of extraordinary human courage, ambition and sacrifice. The scale of the invasion on 6 June 1944, when more than 130,000 US, British, Canadian and other Allied troops crossed the English Channel, preceded by 23,000 airborne soldiers, is staggering; it remains the largest amphibious assault in history. The names of the Normandy beaches Omaha, Utah, Juno, Gold, Sword onto which young soldiers threw themselves under heavy fire have passed into the language as examples of extreme bravery. The events of Operation OVERLORD and its subsidiary plans have rightly been chronicled in some fine histories and immortalised in films over the past seventy-five years.

But the ultimate success of the invasion force, and the 2 million Allied personnel who fought their way across Europe in the following months, tends to obscure just how risky the operation was and how precarious its early days and weeks. So uncertain were the first twenty-four hours that General Eisenhower, as Supreme Allied Commander, famously drafted a statement accepting full personal responsibility for its failure, which had been based on the best information available. The key part of that information, alongside everything from weather forecasting to estimates of the topography of the landing beaches, was intelligence. Examining the role of that intelligence and its importance to the Allied victory has been the subject of a number of studies, often focusing on the gripping stories of deception operations by secret agents to convince German commanders that the attack would take place elsewhere, or dummy landing craft designed to fool German reconnaissance flights. But until now there has been no single account which tells the story of the central role played by Bletchley Park and evaluates its importance.

Since the veil was lifted in the early 1970s on the codebreaking work of the Government Code and Cipher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park, historians have tended to focus on three areas. There are detailed technical accounts of mathematical and cryptanalytic achievements and how machines like Enigma were broken; biographies of extraordinary and sometimes eccentric individuals whose contributions were seminal, notably Alan Turing; and popular accounts of the unusual daily life of staff at Bletchley Park. What has sometimes been missing, particularly in relation to D-Day, is an evaluation of what the intelligence that was produced actually achieved and whether it made a significant difference. Codebreaking was not an end in itself, intellectually challenging as it was, and unless it could be used by the right people in a timely way it was of little value.

Addressing these questions, David Kenyons book breaks new ground in a number of areas. In addition to a highly readable account of how Bletchley Park came to be, and an admirably comprehensible description of the codebreaking process, he focuses in a new way on the intelligence production factory which Bletchley Park had become by 1944. It was no longer a small-scale and eclectic operation, but, from the large network of Y stations intercepting traffic, passing it through Bletchley and its subsidiaries to commanders in the field, it had become a slick and agile industrial producer of intelligence. Just as importantly, Bletchley was by now assimilating intelligence from sources way beyond intercepted messages, a point brought out in depth here for the first time.

This account therefore shows GC&CS at the very height of its powers and reach. It was grappling with all the problems which those of us who worked in its successor organisation, GCHQ, will recognise: constantly keeping up with new technology or cryptological advances by the enemy; disseminating intelligence to the right commanders in a timely way that made it predictive, rather than purely academic; and prioritising from a vast volume of traffic to find intelligence that would be game-changing.

As this book reminds us, Bletchley Park could only decrypt a very small percentage of the messages intercepted. Choosing which traffic to select was therefore critical. Much of the focus in popular accounts of the codebreakers has been on Enigma and this was certainly of vital importance throughout, especially in winning the Battle of the Atlantic, without which an invasion across the English Channel would have been unthinkable. However, this study rightly emphasises the importance of other achievements: the cracking of the Lorenz machine which allowed access to the messages of the German High Command, and the American breaking of Japanese diplomatic ciphers, shared with Bletchley, which enabled the Allies to read detailed Japanese accounts of German plans in Europe.

The result, as this book shows, was that GC&CS was producing an unparalleled insight into German thinking, strategy and detailed orders of battle. This was of enormous practical importance for Allied commanders: they had never been better informed about the enemys strength or its plans. This picture was not complete or perfect intelligence rarely is but it gave assurance to commanders about the threats they were facing and the risks they were taking. From Hitlers and Rommels personal thinking, to battle orders of local commanders and whether the clever Allied deception operations were working, there was little that GC&CS could not shed some light upon.

Pace was a constant challenge for GC&CS, particularly as the Normandy invasion itself got underway. David Kenyon describes the gripping drama of the first day and his account is infused with stories of individuals which bring the history to life. For students of intelligence, his insights into the human management challenges of the SIGINT factory that GC&CS had become are particularly valuable.

As the official research historian at Bletchley Park, Kenyon could be forgiven for eulogising its achievements. But he never overstates its value and subjects some previous claims to scrutiny. He examines perceived failures, for example the suggestion that Allied intelligence missed the scale of German forces defending Omaha beach. His conclusions about the importance of ULTRA material in very significantly reducing the risks of the invasion for the Allies are all the more powerful as a result.

The final D-Day tribute should always go to those who died, some 10,000 Allied soldiers on the first day alone. Key staff at Bletchley appreciated, as the days unfolded, the scale of suffering of those fighting in France, in contrast to their own work in the safety of Bletchley, however exhausting it might be. That those Allied casualties were significantly lower than the figures estimated by Eisenhowers planners, and that their sacrifice led to victory, is where Bletchley Park can rightly claim to have played a major role. David Kenyon has done us a great service in uncovering and describing how this happened.

Next page