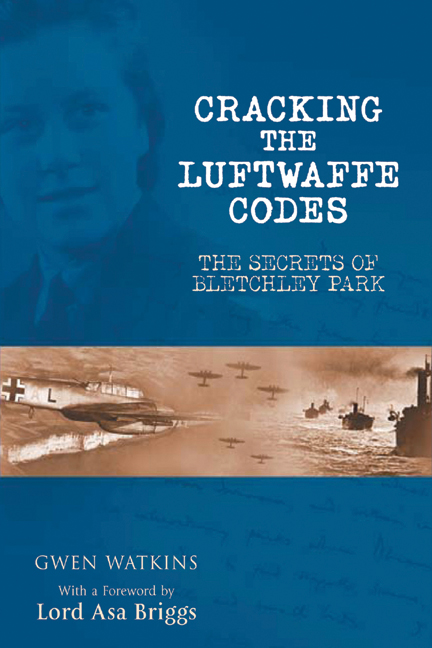

A Greenhill Book

First published in Great Britain in 2006 by Greenhill Books, Lionel Leventhal Limited

www.greenhillbooks.com

This paperback edition published in 2013 by Frontline Books

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

www.frontline-books.com

Copyright Gwen Watkins, 2006

The right of Paul Britten Austin to be identied as the author of this work has been

asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-84832-682-8

eISBN 978-1-78303-660-8

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

For more information on our books, please visit

www.frontline-books.com, email info@frontline-books.com

or write to us at the above address.

Edited and typeset by Wordsense Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound in Great Britain by the MPG Books Group

For David Wendt

Without whose generous help and prodigious memory this book could never have been written

Dear David,

In those far-off days when we were both young and both at Bletchley Park, you seemed to me to have one fault: you were absurdly modest. You never seemed to realise that other people could not have done the things that you did, nor have made the discoveries that you made. And now, in your eighties, you still have that fault.

When the Defence Signals Directorate (DSD) awarded you the Australia Day Medallion for your numerous rsts in a very difcult area, your rare ability to assimilate and correlate minor pieces of information, the originality and accuracy of your research, which contributed signicantly to DSDs high standing in the SIGINT community, you said that the medallion might have gone to a chauffeur or cleaner it just happened to have come round to you.

But your employers knew better. When you retired, they said that during your twenty-two years in the DSD you had acquired the reputation, not only in your own organisation but also in many others, of being an expert in your own eld and for being responsible for many signicant achievements in that eld. It was the same at Bletchley, wasnt it? You did extraordinary things, and always thought that anyone else might have done them.

So, do you believe now that you were brilliant, and that no one else could have done what you did?

No, of course you dont.

GMW

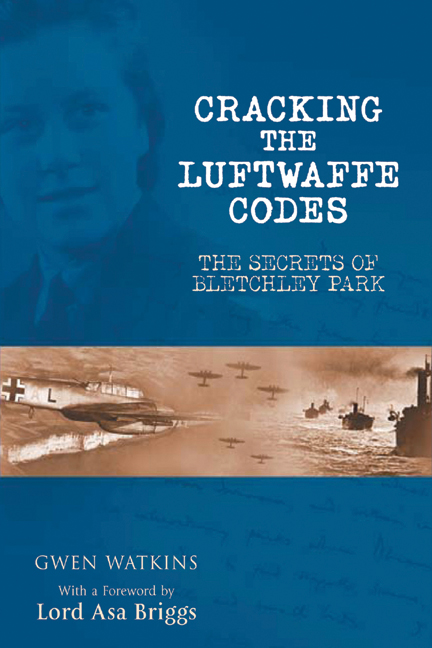

Illustrations

J. E. S. Cooper (Josh)

The author (as Sergeant G. M. Davies) on arrival at Bletchley Park, May 1942

Sergeant Robert Hivnor, US Army Intelligence Corps; German Air Section

Vernon Watkinss fellow code-breakers in Hut Fifty-four, RAF Church Green

David Wendt with a friend in Bletchley Park days

Cartoon on the importance of not being intellectual

Certicate of Discharge from the RAF

Flight Sergeant Vernon Watkins with the author (his wife Gwen) and his daughter, January 1946

Letter from Vernon Watkins to Janet Downs, a fellow code-breaker, 1946, with a drawing of Vernon by Janet

Letter from Robert Hivnor to the author about Codebreakers , 1994

An issue of the Hut Fifty-Four journal, 1960

Letter from Janet Downs to the author, after seeing the TV programme Station X , 1999

David Wendt, 2003

Preface

M OST OF THE BOOKS about Bletchley Park in the 80s and 90s were written or compiled by the pundits, who had worked there from before the war and knew all about Enigma, Ultra and all that stuff. Their books were full of mind-bending technicalities, such as If the consistent set of steckers of Z, V, O and Y contains only one letter of the last four chains, this will imply letters for the other stecker(s) of the chain which could conceivably result in a contradiction But my book had nothing in it like that, because I knew nothing about Enigma until many years after the war, and was in any case one of the lowliest of code-breakers, working with furrowed brow on fairly simple codes.

The critics, probably dreading another mind-bending volume, were proportionately grateful, and were kind to it. One said almost affectionately that he liked the chubby format of the book: it is nice, it doesnt slip out of your hands if your eyes close. Another heartily advised anyone who simply liked a good read to buy it, which is the sort of criticism that goes straight to an authors heart. It was nice to be told that I had written a compelling rst-hand account of Britains battle to crack the German codes, because it had sometimes seemed to me that I had written a rather self-indulgent book about myself, my friends, where we lived and how we amused ourselves in the Second World War. I greatly admired the American critic who, probably too young to be greatly concerned about a war which was over before he was born, frankly confessed that he was particularly fascinated by the Appendix on wartime food. I sympathised with him; it was an interesting subject, and I could have put in some rather nice recipes too, if I had known that anybody would care.

I was grateful, too, to readers who wrote to tell me what they thought of the book. Most of these letters came from people who had worked in the Intelligence or Signal services, many from outstations as far aeld as Cheadle, Chicksands or Beaumanoir; another book could have been written from their reminiscences. But the most precious of all letters were those from the friends a dwindling band of survivors who had actually been with me in Mr Bs section. These brought me great joy; darling Tim E, the now illustrious Lewis R., titled and with many letters after his name and with a pleasant story connected with his mention in the book. The publishers received a letter from the National Museums of Scotland, asking permission to exhibit the photograph of the occupants of Hut 54 as we do not possess a wartime image of Sir Lewis. Theres glory for you, as Humpty Dumpty said! Besides this, I had a splendid letter from Ann Lavell (now Cunningham), prestigious PA to dear Josh Cooper himself, giving me news of my dear friend Beanie, with whom I spent happy leave days, wandering around Oxford and watching undergraduates and Servicemen (often American) fall helpless before her many charms. Also, splendidly, an email from one of Joshs nieces, asking if he was really as eccentric as his contemporaries had said. I was able to tell her stories which proved that indeed he was (though Ann assured me that Josh threw his coffee cup into the lake only once but popular mythology had him doing so every summer evening). And what to answer to the insomniac friend who, having no interest in cryptography, picked up my book one night to send him to sleep, but found himself still reading at 6.30 the next morning? Neither Sorry nor Oh, I am glad exactly expressed my feelings.

In order to correct any typos (which I used to call misprints; thank you Ann, for bringing me marginally up to date), the author has to read through the whole book. This brought all that strange life, so many years ago, before me as though in one of those glass globes that enshrine a tiny scene. Outside Bletchley Park, our lives were much like those of other people living or staying in Britain. If we travelled to certain areas we were in danger of being bombed or having a V1 or a V2 crash down upon us, or on our homes or loved ones. Relatives and friends serving abroad might at any time be killed or mutilated or taken prisoner. We put up with all the shortages of food, clothing and other items too numerous to mention but wildly exasperating; not to possess a match if you were billeted in a house where candles were the only means of lighting seemed to be the last straw when you came off the midnight shift. In all these things you were the same as everyone else; only, outside the Park, you could never breathe a word of what you did inside it. This led to a closeness with your friends and fellow-workers which has been commented on by most people who have written about their time at Bletchley. They were the only ones who understood what this silence meant when you went home or met other friends, or when someone you loved died, and you had never been able to speak about how your days were spent. But we hoped (and some of us knew) that this silence was the price of winning the war, and it was after all a small price to pay. Thousands paid an innitely greater price. The consequences of losing that war would have been more appalling than anyone now living can imagine, and we were intensely grateful that we were allowed to take a small or a great part in saving the world from that disaster.

Next page