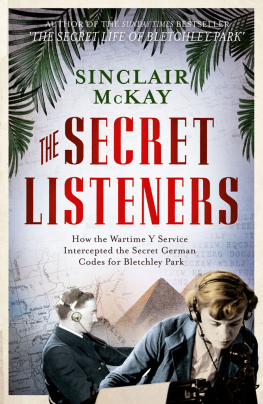

The Secret Listeners

Through the silence of the night, they were listening to the heart of the conflict. In stark rooms with green-shaded lights, furnished with plain desks and chairs and tables upon which rested the sleekest new wireless equipment smooth grey bakelite, black metal, the vanilla glow of illuminated dials dedicated women and men would sit, their ears clamped in warm headphones, in a strange half-world. The signals they were receiving might occasionally have been actual voices, although more often they were the abstract, monotone dots and dashes of Morse: but these coded messages represented chillingly implacable determination, explosive anger and frustration, intrigue and intelligence, and sometimes even the poignant laughter of fear.

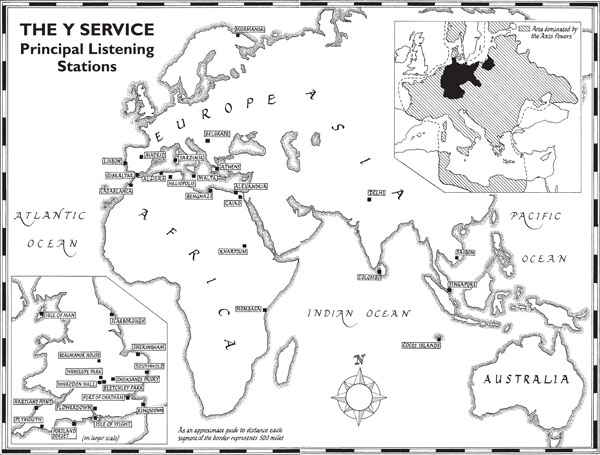

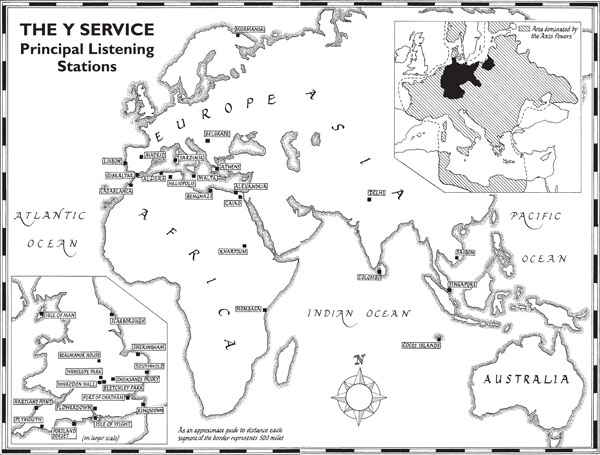

Wherever in the world the operative was working from Englands south coast to the Orkneys, from Murmansk to Cairo, from Mombasa to Delhi to Hong Kong the 2 a.m. watches were the worst. For Victor Newman in Colombo, nocturnal watches might be disrupted by mighty storms, violent rain smashing down on woven palm leaf roofs. In Alexandria, apart from the perpetual banes of dust and sand and flies, night shifts for Special Wireless Operator Bob Hughes would sometimes be made impossible by distant thunder, which would create agonising feedback this terrible crackling in the headphones. In Singapore, Joan Dinwoodie suffered from the relentless suffocating heat, the perspiration running into [her] shoes. Meanwhile, in the middle of the Indian Ocean, on the tiny, barely inhabited Cocos Islands, nineteen-year-old Peter Budd would start a night shift by walking to his listening station through the profound and eerie darkness of the palm trees, taking great care to avoid the lethal insect life whose venom had completely paralysed one of his predecessors.

In every station, the listeners had one thing in common: they worked punishing round-the-clock rotas, with after-effects that some would continue to suffer years after the war. This was as true for those working deep in the familiar English countryside as those in far-off lands. But their work was more than crucial. These young people were intercepting coded messages sent by the Germans, seeking out and faithfully transcribing the chaos of communications first scrambled by the Enigma encryption machines with their almost countless permutations and then sent via radio on ever-elusive frequencies. The listeners would pluck apparently random letters from the air and, having instantly translated them from Morse, send them on to the British codebreakers based at Station X, otherwise known as the requisitioned country house of Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire. Some listeners particularly those in the field in Bletchley out-stations would both intercept and decode the signals they received. The work was fantastically demanding, at every level.

It is sometimes said that the life of a soldier in a theatre of war is 90 per cent boredom and 10 per cent terror and exhilaration. For all those women and men listening and recording the course of war, the proportions were not so very different. But a soldiers attention could at least wander; there was no such luxury for those crammed over wireless equipment, trying to pluck order from an ocean of fuzzy noise. More than this: accuracy was paramount. A misheard signal concerning manoeuvres or forthcoming air raids could cost lives. Boredom a word not allowed, noted Wren and Y Service veteran Joan Nicholls.

For Maurice de la Bertauche, a precocious seventeen-year-old wireless operator based at one of the larger listening stations in the Midlands, such disorientating days would start loweringly. One entered the bus to be met by a fug of cigarette and pipe smoke and a prevailing atmosphere of depression, he wrote. The bus drove operators from their Northamptonshire billets to the country house of Beaumanor Hall. One came to a brick building disguised as a country cottage. Beyond the entrance vestibule, containing coat hooks and smelling of damp clothes, one could detect the smell of ozone from the thermionic valves used in the short wave receivers.

The handover from the previous watch was brisk; on nights and days when the airwaves were filled with noise, when battles were being fought and won and lost, time could not be wasted. If you relieved an operator who was recording a message, wrote de la Bertauche, the person being relieved would turn up the volume control, slip off his headphones, while still recording the message, hand the headphones to his relief, who at an appropriate moment would continue writing down the message.

This young man at least had the consolation of working in a busy room with several dozen other wireless operators. For many young women around the country, in smaller listening posts on the coast and for the young women posted overseas to countries stranger and more exotic than they could have imagined these small-hours shifts were not so much depressing as unsettling. Oh, the night shifts, says Jean Valentine, who having been posted to Colombo in what was then Ceylon was breaking Japanese codes for Bletchley Park out of a low building fretted with palms, and assailed by a rich variety of tropical flying insects. Of course night shifts were lonely. You were there all by yourself, for those eight hours, and the only person you saw was the sailor who came in every hour, or every couple of hours, with a batch of new signals for you to sort out.

And for those listeners in exposed positions on the British coast, or in far-off places such as Tangier or the Western Desert, Malta or Colombo, the threat of being shelled or bombed was ever present. On one night watch in the listening station at Scarborough, a Wren was upbraided by her superiors for having failed to keep a constant record of a stream of messages exchanged that night. Her matter-of-fact excuse was that she kept on having to run outside to swat away incendiaries with a bat; her post had been targeted by bombers and just one incendiary bomb could have set the place alight. Twenty-three-year-old Womens Air Force volunteer and wireless interceptor Aileen Clayton posted around the Mediterranean throughout the conflict was strafed by a German fighter on Malta while on her way to her shift. She took it with remarkable good humour.

The work carried out by these thousands of women and men was intensely skilled; it was also extremely pressurised. Accuracy in relaying these coded enemy messages could mean the difference between life and death. The efforts of those men and women are sadly and curiously uncelebrated today. While the codebreakers of Bletchley Park who fought so long to achieve recognition are now properly honoured, the many people who made their work possible remain in the shadows. So much so that the very term Y Service is still unfamiliar to many.

Yet it was the Y Service that kept the mighty machinery of Bletchley Park fed with information; it was Y Service operatives who listened in on the entire German war apparatus, every hour, every minute of every day; it was these young people who were the first to hear of any tactical shift, any manoeuvre, any soaring victory, any crushing defeat. The fruits of their labours, dispatched to Bletchley Park at top speed, enabled codes to be cracked quickly and German strategies unravelled.

Some months before war broke out, the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) in essence, the codebreaking arm of the Foreign Office had established itself in a faintly ugly country house on the edge of an unremarkable provincial town. And it was within the bounds of this plain house and its estate Bletchley Park that an extraordinary line-up of the countrys finest minds was assembled. All of them, from the irascible veteran cryptographer Alfred Dillwyn Dilly Knox to the visionary young mathematician Alan Turing, faced an apparently insoluble and frightening problem: a means of breaking the German Enigma codes. The Germans themselves considered their Enigma coding machines simple to use, very portable, yet capable of producing millions upon millions of potential letter combinations completely invincible. Looking deceptively like typewriters with lights, these machines of bakelite and wood, with letter rotors of gleaming brass and discreet mazes of electric wiring, were brilliantly, lethally complex. First the machines would make implacable letter substitutions, and then the operators colleague would transmit the letters, by Morse, in blocks of four or five. With code settings changed every midnight, and the letter substitutions produced electrically, how could any human mind begin to find patterns or order in that storm of random letters?