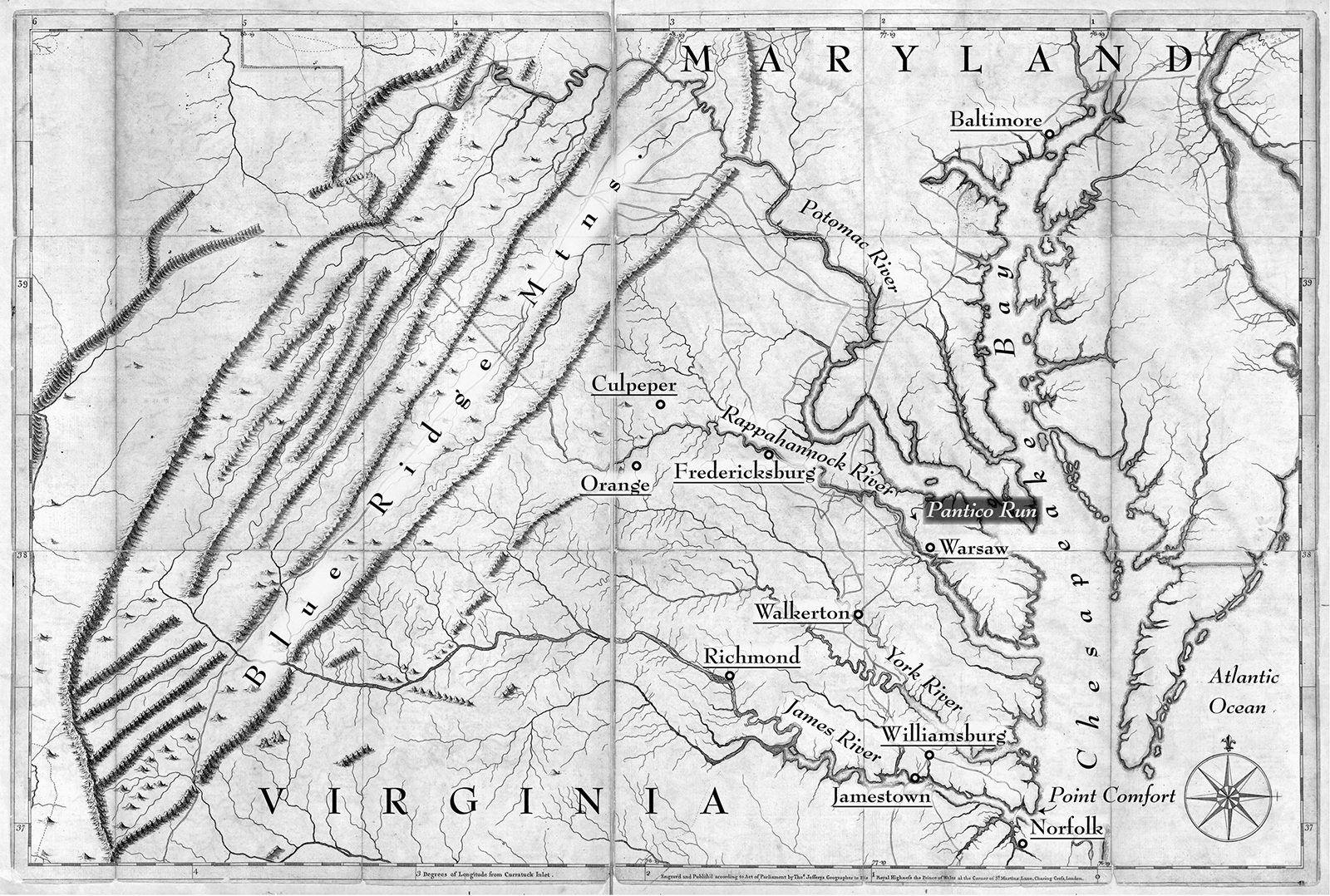

Joe Mozingo - The Fiddler on Pantico Run.An African Warrior His White Descendants A Sh for Family: Joe Mozingo

Here you can read online Joe Mozingo - The Fiddler on Pantico Run.An African Warrior His White Descendants A Sh for Family: Joe Mozingo full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London, United States, United States, year: 2012, publisher: Free Press;Simon & Schuster, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Fiddler on Pantico Run.An African Warrior His White Descendants A Sh for Family: Joe Mozingo

- Author:

- Publisher:Free Press;Simon & Schuster

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- City:London, United States, United States

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Fiddler on Pantico Run.An African Warrior His White Descendants A Sh for Family: Joe Mozingo: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Fiddler on Pantico Run.An African Warrior His White Descendants A Sh for Family: Joe Mozingo" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

My dads family was a mystery, writes prize-winning journalist Joe Mozingo. Growing up, he knew that his mothers ancestors were from France and Sweden, but he heard only suspiciously vague stories about where his fathers family was fromItaly, Portugal, the Basque country. Then one day, a college professor told him his name may have come from sub-Saharan Africa, which made no sense at all: Mozingo was a blueeyed white man from the suburbs of Southern California. His family greeted the news as a larkhis uncle took to calling them Bantu warriorsbut Mozingo set off on a journey to find the truth of his roots.

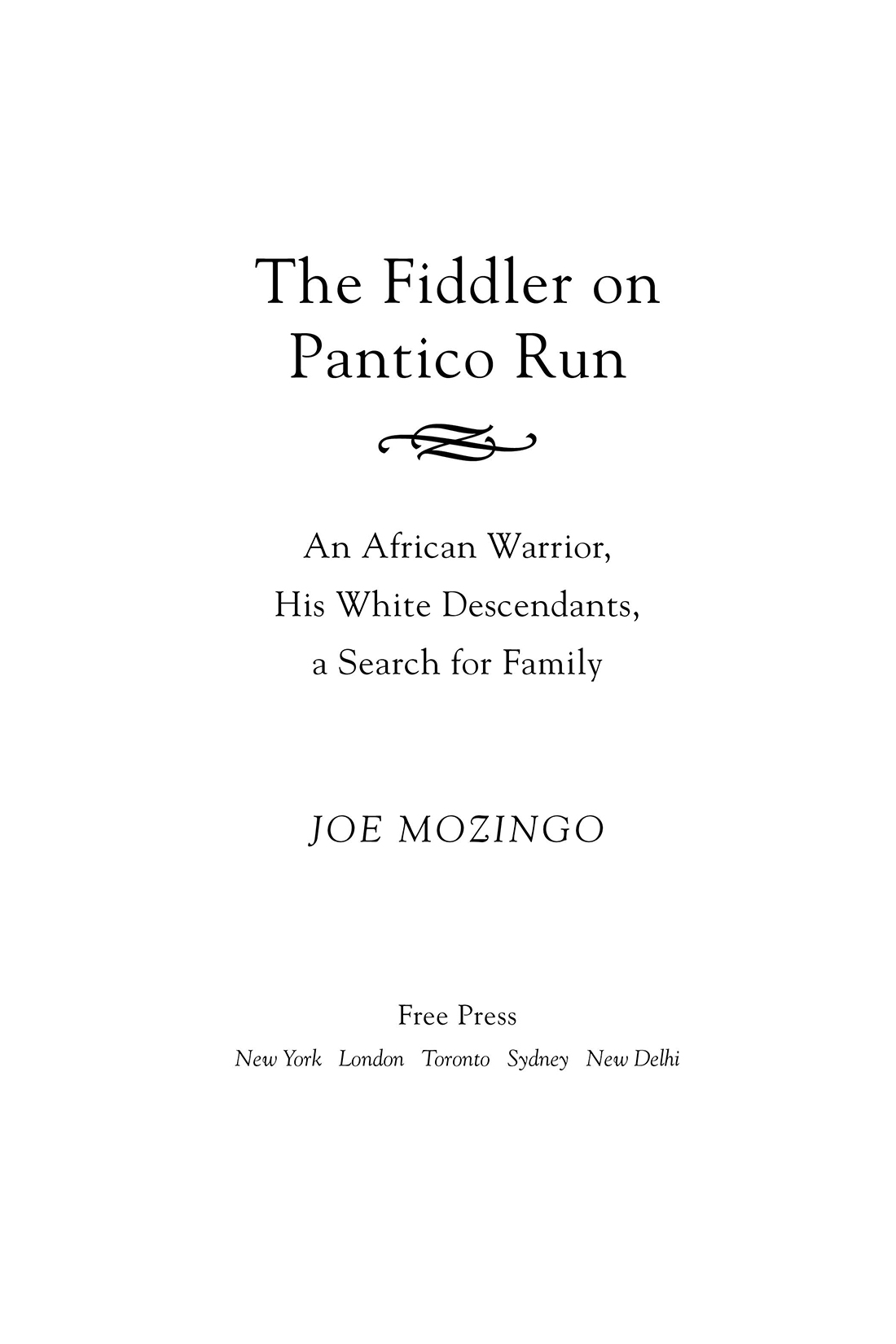

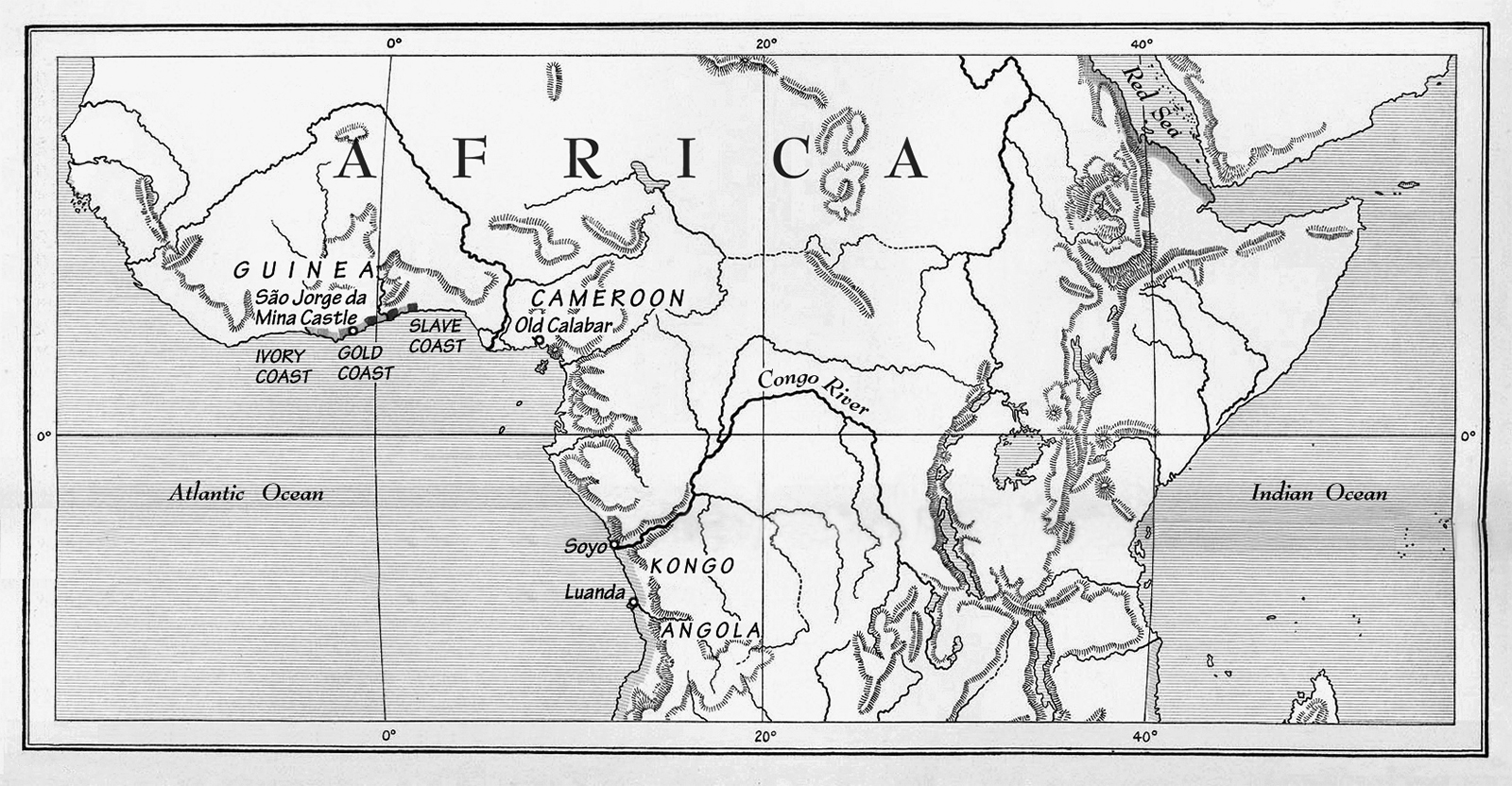

He soon discovered that all Mozingos in America, including his fathers line, appeared to have descended from a black man named Edward Mozingo who was brought to the Jamestown colony as a slave in 1644 and won his freedom twenty-eight years later. He became a tenant farmer growing tobacco by a creek called Pantico Run, married a white woman, and fathered one of the countrys earliest mixed-race family lineages.

But Mozingo had so many more questions to answer. How had it been possible for Edward to keep his African name? When had some of his descendants crossed over the color line, and when had the memory of their connection to Edward been obscured? The journalist plunged deep into the scattered historical records, traveled the country meeting other Mozingoswhite, black, and in betweenand journeyed to Africa to learn what he could about Edwards life there, retracing old slave routes he may have traversed.

The Fiddler on Pantico Run is the beautifully written account of Mozingos quest to discover his familys lost past. A captivating narrative of both personal discovery and historical revelation that takes many turns, the book traces one family line from the ravages of the slave trade on both sides of the Atlantic, to the horrors of the Jamestown colony, to the mixed-race society of colonial Virginia and through the brutal imposition of racial laws, when those who could pass for white distanced themselves from their slave heritage, yet still struggled to rise above poverty. The authors great-great-great-great-great grandfather Spencer lived as a dirt-poor white man, right down the road from James Madison, then moved west to the frontier, trying to catch a piece of Americas manifest destiny. Mozingos fought on both sides of the Civil War, some were abolitionists, some never crossed the color line, some joined the KKK. Today the majority of Mozingos are white and run the gamut from unapologetic racists to a growing number whose interracial marriages are bringing the family full circle to its mixed-race genesis.

Tugging at the buried thread of his origins, Joe Mozingo has unearthed a saga that encompasses the full sweep of the American story and lays bare the countrys tortured and paradoxical experience with race and the ways in which designations based on color are both illusory and life altering. The Fiddler on Pantico Run is both the story of one mans search for a sense of mooring, finding a place in a continuum of ancestors, and a lyrically written exploration of lineage, identity, and race in America.

***

FromThe Fiddler on Pantico Run

As I listened to the dry rasp of the elephant grass, I gazed out over the Kingdom of Kom. A narrow gorge threaded through the lush terrain below, opening into a smoky blue chasm in the distance, the Valley of Too Many Bends. . . . This belt of fertile savannah in western Cameroon rested at a terrible crossroads, with no forest to hide in when the marauders arrived. The kings may have been safe in their fortified isolation, but their people were not. They were taken first by Arab invaders in the Sudan in the north, and then by the southern peoples who found that humans were the commodity Europeans most desired. . . .

Those who survived had been handed from tribe to tribe, through too many hostile foreign territories to dream of escaping and returning home. And then off they went, into the sea.

High on a ridge, three hundred miles by road from the Atlantic, I sat at the headwaters of that outward movement, imagining the people flowing away like the rivers below. I pictured a boy, gazing down into that blue mountain cradle, the grass dry-swishing in the breeze, the drums coming up in the night. A boy suddenly pulled into the current and scrambling to reach the bank. A boy unable to imagine the ocean and sickly white men in big wooden ships and the swampy, malarial settlement called Jamestown where he would be sold to a planter in the year of their lord 1644.

This is the beginning, I said to myself. The beginning of my familys story, the point just after which my forebears obscured the truthand nearly buried it forever

Joe Mozingo: author's other books

Who wrote The Fiddler on Pantico Run.An African Warrior His White Descendants A Sh for Family: Joe Mozingo? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.