GROWING UP WITH THE COUNTRY

THE LAMAR SERIES IN WESTERN HISTORY

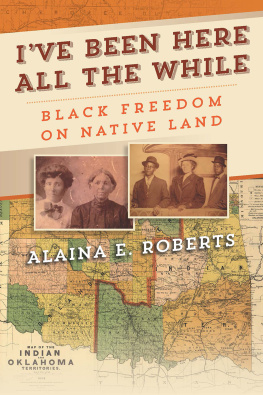

The Lamar Series in Western History includes scholarly books of general public interest that enhance the understanding of human affairs in the American West and contribute to a wider understanding of the Wests significance in the political, social, and cultural life of America. Comprising works of the highest quality, the series aims to increase the range and vitality of Western American history, focusing on frontier places and people, Indian and ethnic communities, the urban West and the environment, and the art and illustrated history of the American West.

Editorial Board

Howard R. Lamar, Sterling Professor of History Emeritus, Past President of Yale University

William J. Cronon, University of WisconsinMadison

Philip J. Deloria, University of Michigan

John Mack Faragher, Yale University

Jay Gitlin, Yale University

George A. Miles, Beinecke Library, Yale University

Martha A. Sandweiss, Princeton University

Virginia J. Scharff, University of New Mexico

Robert M. Utley, Former Chief Historian, National Park Service

Recent Titles

Sovereignty for Survival: American Energy Development and Indian Self-Determination,

by James Robert Allison III

George I. Snchez: The Long Fight for Mexican American Integration, by Carlos K. Blanton

Growing Up with the Country: Family, Race, and Nation after the Civil War, by Kendra Taira

Field

Grounds for Dreaming: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the

California Farmworker Movement, by Lori A. Flores

The Yaquis and the Empire: Violence, Spanish Imperial Power, and Native

Resilience in Colonial Mexico, by Raphael Brewster Folsom

The American West: A New Interpretive History, Second Edition,

by Robert V. Hine, John Mack Faragher, and Jon T. Coleman

Legal Codes and Talking Trees: Indigenous Womens Sovereignty in the Sonoran

and Puget Sound Borderlands, 18541946, by Katrina Jagodinsky

Gathering Together: The Shawnee People through Diaspora and Nationhood, 16001870,

by Sami Lakomki

An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 18461873, by

Benjamin Madley

Home Rule: Households, Manhood, and National Expansion

on the Eighteenth-Century Kentucky Frontier, by Honor Sachs

The Cherokee Diaspora: An Indigenous History of Migration, Resettlement, and Identity,

by Gregory D. Smithers

Wanted: The Outlaw Lives of Billy the Kid and Ned Kelly, by Robert M. Utley

First Impressions: A Readers Journey to Iconic Places of the American Southwest,

by David J. Weber and William deBuys

Forthcoming Title

White Fox and Icy Seas in the Western Arctic: The Fur Trade, Transportation,

and Change in the Early Twentieth Century, by John R. Bockstoce

Copyright 2018 by Yale University.

All rights reserved.

Portions of this book were previously published, in different form, in No Such Thing

as Stand Still: Migration and Geopolitics in African-American History, Journal of

American History 102 (2015): 693718; The Chief Sam Movement, a Century Later:

Public Histories, Private Stories, and the African Diaspora, with Ebony Coletu,

Transition Magazine 114 (July 2014); and Grandpa Brown Didnt Have No Land:

Race, Gender, and an Intruder of Color in Indian Territory, in Gender and Race in

American History, ed. Alison Parker and Carol Faulkner (Rochester, NY: University of

Rochester Press, 2012).

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including

illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108

of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without

written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business,

or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.S. office)

or (U.K. office).

Set in Electra type by IDS Infotech, Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017932063

ISBN 978-0-300-18052-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my father, Kenyon Brown Field (19462004),

my grandmother Odevia Helen Brown Field (19232014),

my mother, Susan Ravensdale Field Malis,

and all those whose stories fill these pages and my heart

The relentless search for the purity of origins is a voyage not

of discovery but of erasure.

Joseph Roach

CONTENTS

Intruder of Color: Freedom, Sovereignty, and

Kinship in Indian Territory

Passing for Black: White Kinfolk, Mulatto Freedpeople,

and Westward Migration

He Dreamed of Africa: Kinship, Class,

and Peoplehood

No Such Thing as Stand Still: The Chief Sam Movement

and the African Pioneers

PREFACE

I n New Jersey, our family was black, while back home in rural Oklahoma we were Creek Indian, too. As a child in the 1970s and 1980s, I loved nothing more than listening to my grandmothers stories about growing up African American and Creek Indian in 1920s Oklahoma. In the long wake of the Newark riots, watching Odevia Brown Field plant tomatoes in the patch behind her house, I learned about a time when our family had owned hundreds of acres of land, alongside our Indian and African-descended kin. Grandpa Brown had a place they called Brownsville, she said, where they built a school and a church. I learned, too, about the oil speculators who gradually came to see my (African-American and Creek) great-grandfather; for the occasional lump sum, he worked as a Mvskoke translator across Oklahoma, telling them just where to look for oil. Through my grandmothers stories, I learned about Indian and African-American land loss.

About once a year, my grandmother would pull out the twenty-five-dollar check she had received from Sun Oil Corporation, insisting that I look at it too. I remember how she stared at that check, asking questions, already knowing the answers. In grade school, I memorized occasional facts about slavery and the Trail of Tears, but it was through my grandmother that I learned about the intersection of the two: that some Native Americans had held slaves, that African Americans had participated in Indian land runs, and that the North American frontier was far more complicated than my textbooks let on. During summertime visits to Oklahoma, I began collecting evidence. Uncle Thurman would take us out to Brownsville, driving red dirt roads for hours, following the perfectly rectangular perimeter of the thousand-acre homeplace. There was no longer a house, but we found the steps to the school, amid a landscape of tall grass, Indian paintbrushes, and oil wells. One year at a YMCA summer camp in the Catskills, when I stumbled across a collection of Indian creation myths nearly identical to the Brer Rabbit folk tales my father occasionally told me as a child, I ran to a pay phone to call him. Was Brer Rabbit Indian, black, or both? These were the wrong questions, but at the time, back east, there was barely language for what I wanted to know. There was, thankfully, the language of family. When I moved away to college, my familys stories stayed with me, quietly highlighting the incompleteness of other historical narratives.

Long before I cared for the discipline of history, my grandmothers stories made me whole, pointing to things I sensed, but for which I had no words. Ronne Hartfield writes, Our mothers stories have given us the maps by which our tribe locates its journeying, its streams and rivers, its stony places, its sometimes astonishing, more often incredibly affirming twists and turns. E. Frances White attests that her own grandfathers stories were so wonderful that I began to believe that they could not be true. As she grew older, however, she stopped worrying about whether they were true. What is important here is that my grandfather

Next page