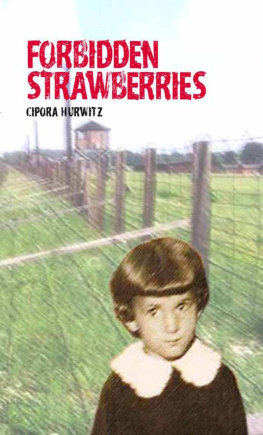

Not learning the lesson taught me by this age.

PREFACE

I remember that which I cannot forget.

(Aba Kovner, Seventy Years)

I do not recall the exact moment I felt compelled to sit down and tell the story of my broken childhood in a book -- a book to be composed of letters that combine to form words, which together depict the terror of Hitlerism, the most horrific embodiment of terror humanity has ever known. How was I able to survive such terror? Perhaps I survived as a result of a young girls will to live. Then again, one-and one- half million other Jewish children also had the will to live. Perhaps I survived by chance, perhaps by luck. I am unable to explain the miracle of my survival based on pure logic alone. I was a girl who grew up before her time.

This book focuses primarily on the physical events that I experienced and their impact on me, my loved ones, and my surroundings. It is impossible to convey a true understanding of the general atmosphere of the period of the Holocaust and the way we felt at the time. What the Jews of Europe experienced under Germanys Nazi rule simply cannot be expressed in normal language, and not even in lofty language. As human beings, we are almost incapable of translating into words the sense of fear that penetrated our souls and which became an important aspect of the nature of the Jewish people. The death sentence that was issued against the Jews was absolute and final.

The Jews throughout history have known many tragedies, but until the Holocaust it was always possible to find a way out, whether through conversion to Christianity, flight to another country, or a pledge of allegiance to the ruling regime. The period of the Holocaust was unique in that its death sentence against the Jews enveloped them completely and with decisive finality. In the pages that follow, I recount the miracle of my survival.

I give testimony in schools, before units of the Israel Defense Forces, and on kibbutzim. I travel to Poland with teenagers and give testimony there as well. I refuse to call Germans Nazis just to be politically correct toward the Germans of today. If we continue to call the Germans who murdered Jews during the Holocaust Nazis, the day will soon come when future generations of Germans will not know who among their people were really the murderers. After all, there is no such thing as a Nazi people. Those who killed were born German, fought for Germany, and, in the name of Germany, and strived to kill anyone and everyone in Europe who was born Jewish.

Although Germany is a democratic country today, I still regard it as the country that murdered everything that was dear to me. Democratic Germany never took serious measures against the soldiers who participated in the killing and never rooted out the evil. Today, the murderers progeny continue to live in Germany in comfort, and do all they can to disassociate themselves from the evils perpetrated by their ancestors, as if nothing significant had taken place. Even today, the members of Josef Mengele family live normal lives, even though they knew where he was hiding all along. His name was not forgotten in the city where he had lived. It was as if Mengele had been just another soldier.

People who experienced the Holocaust as children will always be different, even though they may function normally in the world of the free. Children who experienced such deep hatred and humiliation at the hands of other human beings will never be able to escape the frightening image of those who coolly and indifferently murdered and butchered those around them, as if they were no more than shadows. Those who were born in cities teeming with Jewish life and were suddenly uprooted without taking leave of the landscape, their friends, and of their closest family members will always live in longing.

1. A Visit with a Strange Jew, Years After the War

It was late in the evening and my husband Ariel had already returned home from work when the phone rang in our New York apartment. When I picked up the receiver, I heard a mans voice who identified himself as Ariels childhood friend whom Ariel had neither seen nor heard from in years. I did not know him, but when I told Ariel who was calling, I could see a joyful sparkle in his eye. He quickly took the phone from my hand, and I heard him give his friend an enthusiastic, affirmative response to an obvious proposal being made at the other end. I returned to my own affairs.

As I had no idea who this friend was, I did not listen to the rest of the conversation. Still, the pleased expression on my husbands face made me curious. When he hung up the phone I asked Ariel about the friend. His name was Abe and Ariel explained how he knew Abe. Then, he told me that he had made a date with him for Sunday evening at the home of his friends elderly mother in Manhattan. The reason Abe had come to New York, Ariel told me, was to take his mother back home with him to Chicago.

Abes family left Germany in the late 1930s, along with many other Jews fleeing persecution, the revocation of their rights as citizens, and imprisonment in concentration camps. The majority of these Jews settled on the West Side of Manhattan, not far from the George Washington Bridge. Most lived in red-brick buildings with large apartments. The former U.S. Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger and his family were among them. As the years passed, the German Jews of New York managed to acclimatize to the city and its culture, make a living, and ultimately disperse throughout the United States. Time inevitably marched on for those who stayed in New York. Some moved to old-age homes, and others died. People from many backgrounds and cultures moved into the neighborhood, changing the character and appearance of the area. By the time Abe returned to bring his mother back to Chicago with him, she was the only long-time Jewish tenant left in her building.