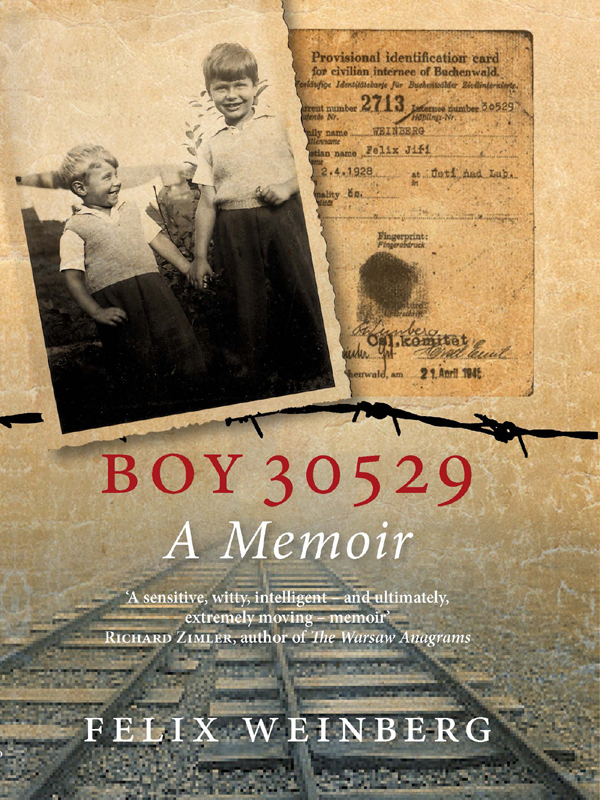

BOY 30529

A Memoir

FELIX WEINBERG

First published by Verso 2013

Felix Weinberg 2013

Foreword Suzanne Bardgett 2013

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN: 978-1-781-68301-9 (e-book)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Weinberg, Felix Jiri, author.

Boy 30529 : a memoir / Felix Weinberg.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-78168-078-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Weinberg, Felix Jiri Childhood and youth.

2. Jews Czech Republic Prague Biography.

3. Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945) Czech Republic

Prague Personal narratives. 4. Jewish children in

the Holocaust Czech Republic Prague

Biography. 5. Auschwitz (Concentration camp)

6. Holocaust survivors England London

Biography. 7. Prague (Czech Republic)

Biography. I. Title.

DS135.C97W438 2012

940.5318092 dc23

[B]

2012043156

Typeset in Fournier MT by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed by in the US by Maple Vail

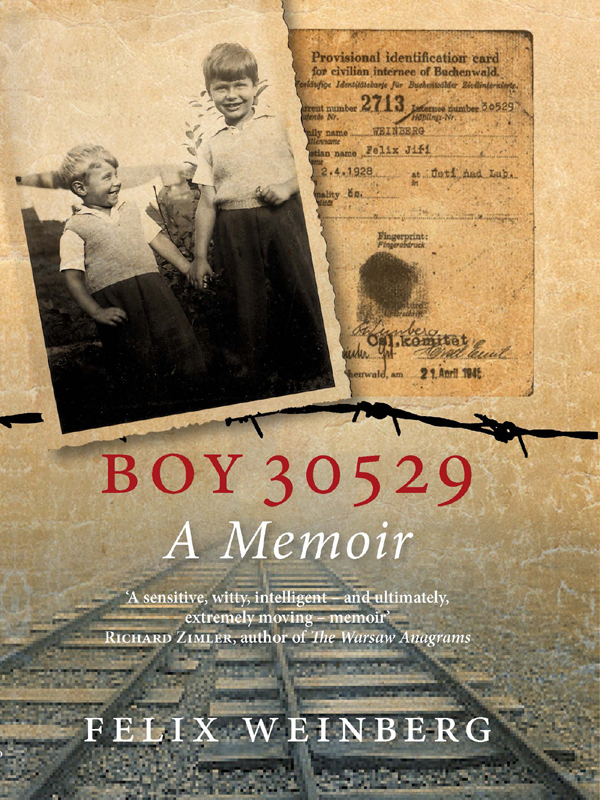

In memory of my wonderful mother, my little brother and all the other unforgettable members of my family who perished under degrading and squalid conditions in Nazi camps.

Back in the mid 1990s, our small team of researchers at the Imperial War Museum were accumulating what they could for the Holocaust Exhibition then being planned for Millennium Year. It was a busy and rather anxious time. We were trying with some difficulty to amass a collection of artefacts for the showcases, and each time a researcher came back from a visit to a survivor with a relic of the concentration camps, it seemed that a further piece of our exhibition was in place.

I remember a particularly unusual item a battered leather jacket arriving in the project office. Its donor, Professor Felix Weinberg, described it as on permanent, if unauthorised, loan from one of the defunct Buchenwald guards.

The liberated SS jacket duly went into the Holocaust exhibition, and in due course I met Felix Weinberg and his wife, Jill. I realised that our donor, who had grown up in Czechoslovakia, was an eminent professor of physics at Imperial College London and briefly wondered how he had managed to make that long journey from child survivor of a series of concentration camps to esteemed professor of science. Professor Weinberg mentioned to me that he had worn the SS guards jacket for many years when riding his motorbike in London, and I remember thinking this showed an admirably defiant attitude to his past captivity.

Several years later in 2011 Felix Weinberg got in touch again. He had decided that he owed it to his family to write an account of his early life, and wondered whether I would like to read it. I did so and was struck by several things: firstly, Felix has extraordinary powers of recollection being able to transport the reader into his teenage mind, where a spirit of scientific enquiry was already taking root. This ability to resurrect his boyhood enthusiasm for how things work, overlaid with the wisdom of later years, and considerable self-awareness, makes it an especially engaging and original read.

Secondly, it is clear just how much Felix Weinbergs eventual survival of Terezn, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Blechhammer, Gross-Rosen and Buchenwald camps owes to the cocooning of his early years. A father who loved playing with his two boys and a mother with an instinctive ability to bring fun into her childrens lives these were the wellspring from which Felix would draw during his two-and-a-half-year captivity. To dream of his past life enriched by doting grandparents, journeys by paddle-steamer on the Elbe and trips by horse-drawn sleigh only to wake up in the stench and misery of the concentration camp barracks was excruciating. But it was these memories together with the chance inner reserves that came from having a father who was a fitness and nutrition fanatic which enabled the young Felix to survive.

Hunger, ill treatment and finally the trauma of Allied bombing left Felix half-alive at the end of the war. His closing chapters lay bare aspects of the liberation of the camps I had not heard about the Wild-West interregnum before the arrival of proper relief organisations saw child survivors blowing themselves up with weapons taken from the arsenal abandoned by the Nazis. The almost apocalyptic scenes Felix witnessed at this point, and their tragic aftermath, stayed with him forever.

To revisit the past in this way cannot have been easy. All those who care about the proper documenting of this horrendous era must be grateful to Felix Weinberg for giving us this insightful and ultimately uplifting account.

Suzanne Bardgett , Head of Research

Imperial War Museum

September 2011

This chronicle would never have seen the light of day but for the influence of a number of good friends. First and foremost it was Bea Green herself a Kindertransportee, who arrived in the UK before the war and is something of an activist in keeping the memory of those events alive who insisted that I owed it to my children and grandchildren to record this history, no matter how harrowing, because they had the right to know. Next, a number of friends and colleagues who asked to see what I had written urged me to share it with a wider readership because, to my utter astonishment, they thought it a good read. Amongst them I am indebted to Drs James Lawton, Darren Tymens, Ivan Vince, professors Charmian Brinson, Rafael and Deniz Kandiyoti and, in particular, three other camp survivors with rather different histories: Peter Frank, Otto Jakubovic, and his wife Angela, as well as Frank Bright. Some of my friends were also most helpful in drawing my attention to omissions and slip-ups, and I can only hope, considering how ancient some of us have become, that I have now succeeded in rectifying most of them.

I am deeply grateful to Suzanne Bardgett not only for writing such a moving foreword but also for providing the one and only opportunity for the Czech boys of my narrative and their descendants and families to meet (some thirty-five in all) at the Imperial War Museum in September 2005. Suzanne arranged the screening of a film of the children climbing into bombers for the flight to England in the autumn of 1945, arranged afternoon tea, and gave us the opportunity to see her magnificent work in keeping the memories of our World War II experiences in public view.

Regarding the battered leather jacket which she mentions and which now graces her display: if there were a prize for the worlds ugliest garment, I would back it as a leading contender. I do not think it was ever designed to be worn on the outside; my guess is it was originally intended to be worn under the Luftwaffe uniform by flight crews operating at high altitudes in order to keep them warm. The main body was stitched together from a large number of small squares of fleece, with the sickly off-white-wash leather facing outward. The sleeves were knitted and loosely attached at the shoulders. The design spoke of a nation poor in material resources but well endowed with slave labour. What made it such a valuable prize, first for a Buchenwald guard and then for me to the point that I brought it on the Lancaster Bomber for the flight to England was that it was uncommonly warm, and certainly the warmest undergarment I ever owned. Perhaps I ought to mention that the Buchenwald guard raised no objections to my taking it, as he was dead at the time, possibly due to an earlier visit by some of my fellow prisoners.

Next page