The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

CONTENTS

Introduction: Until We Meet Again

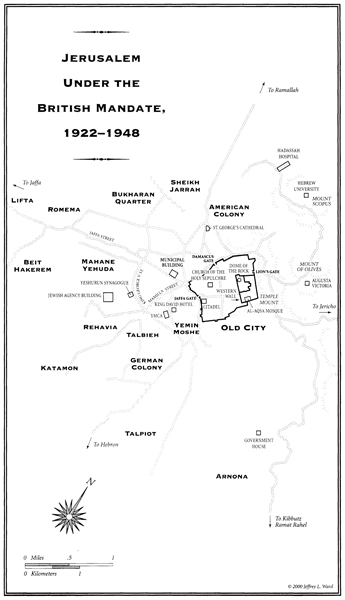

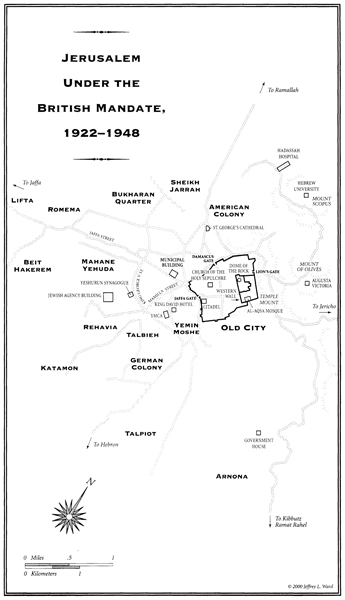

On the southern slopes of Mount Zion, alongside the ruins of biblical Jerusalem, lies a small Protestant cemetery. The path to it wends through pines and cypresses, olive and lemon trees, oleander bushes in pink and white, leading to a black iron gate around which curls an elegant grapevine. Perhaps a thousand graves are scattered over the terraced hill; ancient stones peer out from among red anemones. Not far away, on the top of the mountain, is a site Jews revere as the grave of King David as well as a room in which Catholics say the Last Supper was held; in a nearby basement chamber, they believe, eternal sleep fell over Mary, mother of Jesus. The Muslims have also sanctified several tombs on the mountain.

Bishop Samuel Gobat consecrated the cemetery in the 1840s to serve a small community of men and women who loved Jerusalem. Few had been born in the city; the great majority came as foreigners, from almost everywhere between America and New Zealand. Engraved on their headstones are epitaphs in English and German, Hebrew, Arabic, and ancient Greek; one headstone is in Polish.

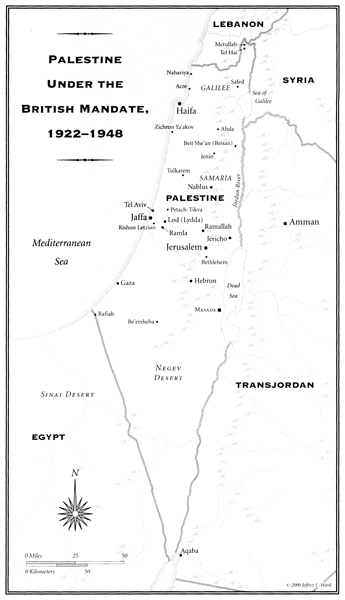

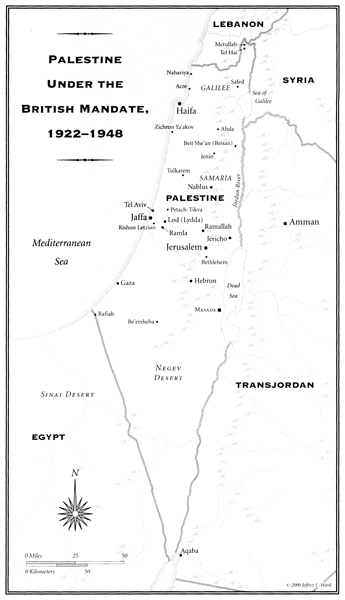

When the first of the dead were interred here, Palestine was a rather remote region of the Ottoman Empire with no central government of its own and few accepted norms. Life proceeded slowly, at a pace set by the stride of the camel and the reins of tradition. Outsiders began to flock to the country toward the end of the century, and it then seemed to awake from its Levantine stupor. Muslims, Jews, or Christians, a powerful religious and emotional force drew them to the land of Israel. Some stayed only a short time, while others settled permanently. Together they created a magical brew of prophecy and illusion, entrepreneurship, pioneerism, and adventurisma multicultural revolution that lasted almost a hundred years. The line separating fantasy and deed was often blurredthere were charlatans and eccentrics of all nationalitiesbut for the most part this period was marked by drive and daring, the audacity to do things for the first time. For a while the new arrivals were intoxicated by a collective delusion that everything was possible.

An American brought the first automobilethat was in 1908. He traveled the length and breadth of the country and created a sensation. A Dutch journalist arrived in the Galilee, dreaming of teaching its inhabitants Esperanto. A Jewish educator from Romania opened a nursery school in Rishon LeTzion, a tiny experimental Zionist settlement, and was among the editors of the first Hebrew childrens newspaper. Someone began making ice creamthat was Simcha Whitman, who also built the first kiosk in Tel Aviv. A man named Abba Cohen established a fire department, and a Berlin-born entrepreneur built the first beehives. A Ukrainian conductor founded a local opera company, and an Antwerp businessman set up a diamond-polishing shop. A Russian agronomist who had studied in Zurich planted eucalyptus trees, and an industrialist from Vilna launched Barzelit, the first nail factory. A Russian physician, Dr. Aryeh Leo Boehm, set up the Pasteur Institute, and a man named Smiatitzki, who came from Poland, translated Alice in Wonderland into Hebrew.

Tens of thousands of people, most of them Jews, came from Eastern and Central Europe. Among them were courageous rebels searching for a new identity, under the influence of Zionist ideology. Others had fled persecution or poverty; most came unwillingly, as refugees. A. D. Gordon, a white-bearded farmer-preacher, a kind of local Tolstoy, proclaimed a gospel of manual labor and return to nature in the Galilee. He had come from the Ukraine and was one of the fathers of labor Zionism, the political movement that led the Jews to independence. A young woman, fanatic and mad, galloped over the Galilee mountains dressed in Arab garb; her name was Manya Wilbushewitz. She came from Russia, where, in great spiritual turmoil, she had pledged her soul to the Communist revolution. In Palestine she was among the founders of a communal farm, an early incarnation of the kibbutz, and one of the first members of HaShomer, a forerunner of the Israel Defense Forces. Some Jewish immigrants embarked on new lives in the first Zionist agricultural villages; others decided to build themselves a new city on the Mediterranean shore. It was called Tel Aviv.

The Christians, for their part, brought with them the imperial aspirations of their native lands; they were drawn largely to Jerusalem. And so Palestine, and particularly Jerusalem, became a veritable Tower of Babel, remarked Chaim Weizmann, who led the Zionist movement.

The founding fathers of the American Colony are also buried in Bishop Gobats little cemetery. Not far from them lies the son of a German banker who financed the first rail link between Jaffa and Jerusalem. The grave of a Polish doctor is nearby. He opened the first childrens hospital, on the Street of the Prophets. On that same street, Conrad Schick, buried next to the doctor, constructed houses that made his reputation as the greatest builder of modern Jerusalem. In his native Switzerland Schick had built cuckoo clocks. On a higher terrace lies an Englishman, William Matthew Flinders Petrie, considered by some the father of modern archaeology. He did much work in Egypt and excavated in Palestine as well. In his old age he settled in Jerusalem, dying at nearly ninety. Before his burial, his widow had his head severed from his body. The head was placed in a jar and covered with formaldehyde, and after being packed in a wooden crate was sent to London for a pathological examination meant to discover the secret of the late mans genius.

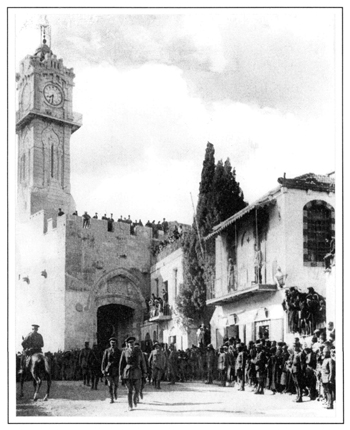

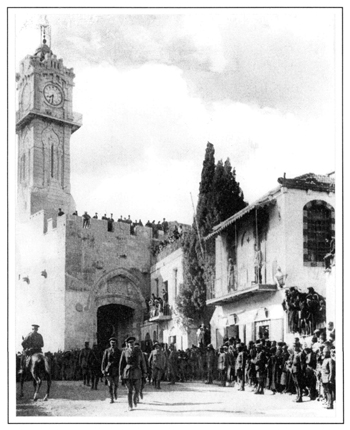

In the Protestant cemetery lie the many foreigners who fell for Palestine, among them soldiers who fought in the strife-torn decades of the Mandate period. Enemies and comrades-in-arms are buried side by side. Adolf Flohl, a German pilot during World War I, had come to join in the defense of his countrys ally, the Ottoman Turks. He was shot down and killed in mid-November 1917, less than four weeks before the British victors marched into Jerusalem and took control of Palestine. Not far from Flohl lies Sergeant N. E. T. Knight, an English policeman. He was killed in April 1948, less than four weeks before the British left Palestine. Together they frame an era of promise and terror.

* * *

The Great War that shoved Europe into the twentieth century changed the status of Palestine as well. For more than seven hundred years the land had been under Muslim rule. In 1917, as part of the British push into the Middle East, it passed into Christian hands; indeed, many of the conquering British soldiers compared themselves to the Crusaders. However, even as the British took control of Palestine the tide was going out on their empire; when they left the country thirty years later Britain had just lost India, the jewel in the crown. Palestine was little more than an epilogue to a story that was coming to an end. In the history of empire, then, Palestine was an episode devoid of glory.