A. J. Sherman

Mandate Days

British Lives in Palestine

19181948

A. J. Sherman, born in Jerusalem under the Mandate, lives in Vermont. He is an Associate Fellow of St. Antonys College, Oxford, where he was for some years Research Fellow. Among his books is Island Refuge: Britain and Refugees from the Third Reich, 19331939.

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include:

In Whose Name?: The Islamic World After 9/11

W(est) B(ank)

The Middle East: The Cradle of Civilization Revealed

The Crusades and the Holy Land

The World of Islam: Faith, People, Culture

War Since 1900: History Strategy Weaponry

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

Preface

In the nearly half-century since the British left Palestine, there has been a virtually ceaseless outpouring of analysis and polemic about the Mandate and its policies, yet curiously little assessment of the experience and self-understanding of British individuals, officials and others, who actually lived and worked in that unquiet country. As if their presence in the Holy Land, their reactions to it, had somehow been irrelevant, the British men and women of the Mandate have with rare exceptions been omitted from histories of Palestine, their daily lives, relations among themselves and with Arabs and Jews unexamined or taken for granted. This book aims to remedy that omission, largely by permitting the participants in the Mandate to tell their own stories. Although a posting to Palestine was never conceived of as a colonial service plum, and the Mandate represented to most British at best a burden and in the end a supreme mortification, those who served there ultimately came to feel their own version of imperial nostalgia. If few of the British community stationed in Palestine ever fully understood the growth of Arab nationalism, or the dynamics of the Jewish state within a state that was to become Israel, virtually all were affected by their stay. Mysterious as it was, frustrating and often infuriating, the Holy Land worked a subtle alchemy on its British rulers, and few of them remained untouched by their experience of its peoples, landscape and history.

My own life began in Jerusalem under the Mandate, and I retain a few but vivid memories of earliest childhood there: sunlight on the local stone walls, the scent of eucalyptus trees, snatches of song, certain words in Hebrew and Arabic. Growing up in the United States, I heard countless stories of a life in Jerusalem that even then had an almost mythic quality: a moment in time before the great bitterness of the Second World War, when it seemed not hopelessly quixotic for idealists such as my parents and their small circle to dream of a commonwealth in Palestine in which Arabs and Jews might dwell together in peace. Later, amid the violence of the Jewish revolt against the Mandate, my parents deplored the facile demonizing of Palestines rulers, and recalled individual British neighbours from Jerusalem with respect and sympathy. The lives of those British sojourners in Palestine have always exerted a great fascination for me: perhaps a residue of the childs curiosity about the doings of grownups in authority. Their voices, quite unmistakably of their time and that place, continue to resonate from the texts to which that last generation of assiduous letter-writers and diarists confided feelings as well as facts about where they were and what they were doing.

The British of the Palestine Mandate left a vast trove of private papers, and I am most grateful to the custodians of those collections to which I had access. I am in the first place indebted to the Warden and Fellows of St Antonys College, Oxford, for welcoming me on several lengthy visits to their most agreeable society. It is a particular pleasure to thank Dr Derek Hopwood, Director of the Middle East Centre, St Antonys College, Oxford, who generously assisted me in consulting the rich archive of Private Papers deposited there, largely through the initiative of the late Miss Elizabeth Monroe. I wish also to acknowledge the efficient helpfulness of Mrs Diane Ring, Librarian of the Middle East Centre, St Antonys College, and of Mrs Clare Brown, Archivist of the Private Papers Collection. My thanks are due as well to the librarians and staff of Rhodes House, Oxford; the Imperial War Museum, London; the Research and Jewish Divisions of the New York Public Library; and the library of Middlebury College, Vermont. The staff at the Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem, in particular Mr Reuven Koffler, curator of the Photographic Archive, were most helpful in locating materials I would not otherwise have seen. I am grateful to Mr Stephen Bank for his contributions to the Biographical Index. I am much obliged to Thames Television for permission to quote from transcripts of interviews broadcast in 1978 in their series on the British Mandate in Palestine; to Mr Leslie Perowne, for his consent to my quoting from his late brothers papers; to Miss Mary K. Burgess for allowing me to quote from her letters; and to Mr R.D. Chancellor, for leave to quote from his late fathers papers.

I have also been fortunate in the kind assistance and encouragement of the following, to whom I offer collective and individual thanks: Dr David Arnow; Mrs Anna Biegun; Mr and Mrs R.D.N. Bird; Sir Isaiah Berlin; Maj. General H. Bredin; Professor William Brinner; Dr Jules Cashford; Professor E. Mason Cooley; Lord and Lady Dahrendorf; Faith Evans; Mr James Hatch; Mr Edward Horne; the late Mr Albert Hourani; Mr J.D.F. Jones; the late Mrs Philippa Keith-Roach; Professor Christoph Kimmich; Professor A.H.M. Kirk-Greene; Mrs Mary MacKenzie; Professor Margaret Macmillan; Mr Theo Mainz; Mr R. David Mann; Dr Jorge Martn; Professor Joseph Nevo; Professor Joaqun Martinez Pizarro; Mr Steven M. Riskin; the late Mrs Sarah Stein; Mr Anthony Verrier; Mr George Warburg; Professor David Wasserstein; Professor Michael Wood. To several others, who prefer anonymity, profound thanks for insights and information.

Although I have greatly benefitted from the views of several friends and critics, I remain solely responsible for the entire contents of this book. It is, finally, salutary to be reminded, in the words of Benny Morris, that the possibility that his findings and conclusions might subsequently be used by propagandists and politicians of this or that ilk is surely no concern of the historian.The historian must be judged acording to the degree of accuracy and understanding he has achieved regarding the past nothing else.

A.J.S

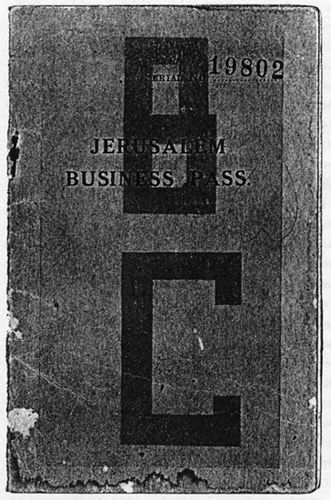

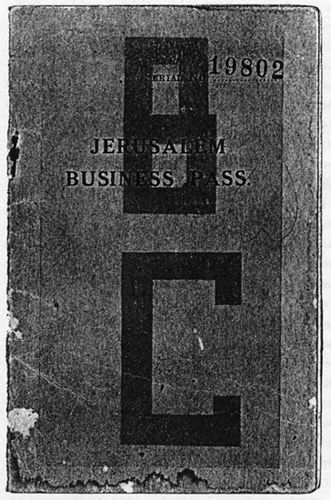

Jerusalem security pass used by British residents

chapter 1 ~ In the Beginning: 19171920

The British Mandate in Palestine, surely one of the least glorious episodes in the long history of the Empire, was nonetheless one of the great dramas in that history, productive of more emotion and certainly more criticism than any other part of the vast enterprise. The Mandate, in form a trusteeship under the authority of the League of Nations over a territory inhabited by peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the conditions of the modern world, was in fact consistently administered as a Crown Colony, to the abiding frustration of all its inhabitants. As to Palestine, Eretz Israel, Filastin: the very names of the country have always aroused passion, an immense freight of history, the clash of ideologies, communities and individuals. The phrase Britain in Palestine also carries an emotional charge, evoking the British Empire at its zenith and in decline, and the whole complex of feelings arising from the domination of non-Europeans by European powers. The nearly fifty years since the Mandate ended have not diminished the strong passions associated with it, either in the Middle East or elsewhere: British policies, promises, her mere presence in Palestine are all still argued, deplored, or less frequently admired.