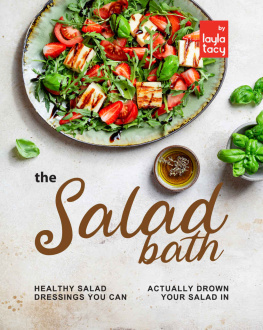

To my husband, Adam, who has spent countless hours analyzing every salad in this book, and who desperately deserves a pizza.

Foreword Part I; Christine Muhlke

Christine Muhlke is the editor at large at Bon Apptit.

MoMA PS1 was closed, but I wasnt there to see the art. I was there to eat it. Julia Sherman had invited me to a lunch made from the garden she built on the roof. It was August, and even though she had hosted a summer of edible events with food gathered from the raised beds, the plants were still abundant and getting a little wild, bolting against the Manhattan skyline.

Only ten minutes from Midtown, I was being fed just-blitzed gazpacho and salads bearing elements from every bed. There was cornbread sprinkled with herb salt shed blended and poured into amulet-like vials; and herbal agua frescas to drink. It was delicious, of course, and how cool to be able to eat and talk on a rooftop above an empty museum while everyone else I knew was staring at their phones while waiting in line for salads trapped in plastic domes. More importantly, it popped open a door in my imagination: How cool to have a simple, radical ideaI want to build a garden on the roof of a museum and ask artists to come make saladsand then bring it so fully to life. What would she pull off next?

Making and serving food is not a new art form. From Gordon Matta-Clarks 1970s restaurant, FOOD, to Rirkrit Tiravanijas gallery curries of the 90s (and, now, upstate restaurant, Unclebrother, with gallerist Gavin Brown), the public has consumed the work. But for Julia, the work also involves curating experiences and discussions, bringing food and artists together as she invites them to share their processes and discuss how it relates to their own art, then sharing it through her blog, Salad for President.

It was Madeleine Fitzpatrick who taught me five years ago that making a salad could be a form of artistic expression. The otherworldly painter led me into her anarchic garden in Marin County, big metal bowl in hand, and began gathering wild-seeded leaves, fruit, flowers, shoots, sprouts, seeds, and probably grasses. When the bowl hit the dinner table, guests, including some of the Bay Areas greatest chefs, were firmly instructed to eat it with their fingers. They did as told, eyes closed, then opened wide in surprise as they came across some beautiful element theyd never experienced before. That saladif you could call it thatbrought us together. It was a creation, a performance, never to be repeated.

Madeleine is here on , sharing her wild wisdom. Youll find artists like Laurie Anderson, William Wegman, and Tauba Auerbach, too. There are recipes, of course, but you dont have to follow them to the letter. Salad for President is about inspiration, about making and sharing something bright and beautiful that has been gathered from whatever moves you.

Foreword Part II; Robert Irwin

Robert Irwin is a conceptual artist and seminal member of the Light and Space Movement that emerged from Southern California in the 1960s. In 1997, he created the Central Garden at the Getty Center, an evolving work of art that continues to draw millions of visitors to this day.

This is an excerpt from a conversation between Salad for President and artist Robert Irwin, November 2015.

Julia Sherman: You are not a gardener or a landscape designer, but some of your best-known works take the form of gardens or architectural spaces. Are there any limits to what you can do as an artist?

Robert Irwin: I decided a long time ago that being an artist had something to do with how we exist in the world, and that it shouldnt be limited to painting, sculpture, or the studio. So I got rid of the studio years ago and spent a little while just wandering around. I developed the idea of Conditional Art: You give me a set of conditions and I will respond to them. With this idea of an artist, I could plan a city, I could plant a garden, I could be the architect at Dia: Beacon. The artist can essentially operate anywhere in the world with the right setting and an understanding.

JS: But the moment you gave up your studio, did you feel relieved or were you terrified? You make it sound so easy.

RI: Who said it was going to be easy? I felt both. I was nervous, but as long as I remained in the studio, I would keep making studio art. So, my options were: stay in the studio or leave.

JS: So, what does an artist do?

RI: An artist is an aesthetician. We understand the world through feeling, and an artist makes us aware of our feelings in a more interesting and demanding way. Its not about creating paintings and making things.

Introduction

I was born into a family of artists.

My grandmothers met in a sculpture class at New York Citys National Academy School before setting my parents up on a blind date. I grew up in my mothers SoHo studio, where encaustic was an everyday art supply and my first clay sculptures of cats and dogs were cast in bronze. In 2007, in my early twenties, I moved to Los Angeles, where I finally had my first real studio, a storefront in East L.A. that my now-husband and I turned into a not-for-profit gallery called Workspace. After each art show, I carried the excitement from the gallery to our nearby home, where, with ingredients reaped from my vegetable garden, I cooked elaborate meals and served salad to whomever showed up.

Simultaneously, I was trying to define my own work in the privacy of my studio. I raised silkworms and spun their cocoons into thread. I experimented with ceramics, sculpture, film, and photography. When I think back on the time period now, the work I made in my studio exists in a kind of hazy shroud. What I remember clearly, however, is the energy at Workspace and the meals that extended our early evening happenings late into the night. My little side project attested to our collective vision of an art world that was messy and complicated andimportantlyshaped by its participating artists, not by commerce or institutions.

The audience at a Workspace performance in 2008.

I moved back to New York to pursue an MFA. There, I began to use my own art practice as a way to to gain firsthand insight into the way other people approach their art. Why do we make the things we make? I worked alongside a wigmaker in Cusco, Peru; a third-generation cobbler in Burbank, California; a trailblazing drag queen on New Yorks Upper East Side; and a goddess-worshipping weaver. Instead of reinforcing the New York bastion of high culture, I wanted to explore art making as a common denominator that brought unlikely people together, not set them apart.

When it came time to complete my graduate thesis, I found myself living in Connecticut with a community of Benedictine nuns. The brilliant women of the Abbey of Regina Laudis wear denim habits in solidarity with American blue-collar workers. Their mantra is ora et labora

Next page

![Schurman - The Everything Salad Book: Includes Raspberry-Cranberry Spinich Salad, Sweet Spring Baby Salad, Dijon Apricot Chicken Salad, Mediterranean Tomato Salad, Sesame! EhWd]e Coleslaw](/uploads/posts/book/94669/thumbs/schurman-the-everything-salad-book-includes.jpg)