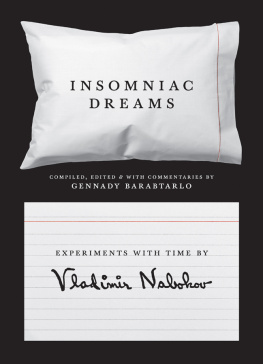

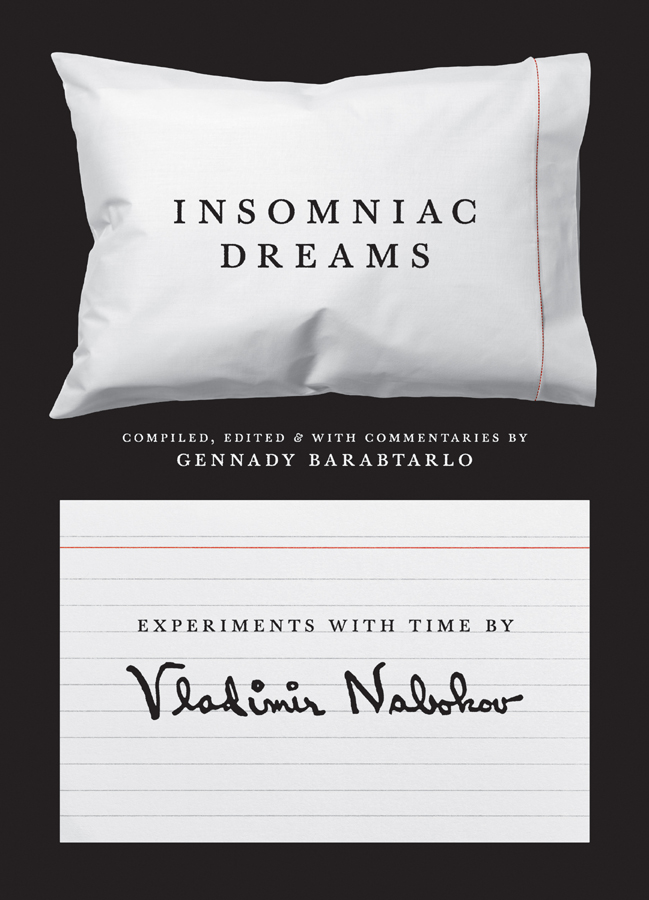

INSOMNIAC DREAMS

INSOMNIAC

DREAMS

EXPERIMENTS WITH TIME BY

Vladimir Nabokov

COMPILED, EDITED, & WITH COMMENTARIES BY

GENNADY BARABTARLO

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton & Oxford

COPYRIGHT 2018 BY THE ESTATE OF DMITRI NABOKOV

Compilation, preface, parts 1 and 5, notes, and other editorial material copyright 2017 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

PUBLISHED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket images courtesy of Alamy

Jacket design by Chris Ferrante

Owing to limitations of space, all acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published material can be found on page 191

FRONTISPIECE: Vladimir Nabokov writing in bed at home in Ithaca, New York, 1958. (Photo by Carl Mydans / Time Life Pictures / Getty Images)

All images in this book except the frontispiece are from the Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Copyright the Dmitri Nabokov Estate. Used by permission of The Wylie Agency, LLC.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ISBN 978-0-691-16794-7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017941575

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Baskerville 10 Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

IN MEMORIAM DMITRI NABOKOV

What is Tme? If no one asks me, I know;

if I wish to explain it to one that asketh, I know not.

St. Augustine, The Confessions, Book XI

CONTENTS

THIS BOOK WAS BORN of the convergence of two initially separate undertakings: a paper entitled Clarity of Vision, delivered at a Nabokov conference in Auckland, New Zealand, and my studies of Nabokovs records of his 1964 experiment with dreams, as well as his diaries, preserved in the New York Public Library. The latter setting, with its sterile, hushed chill soothed by the warmth of the helpful staff, could not be more different from the playhouse of a large university auditorium.

The conference was called Nabokov Upside Down, and my paper was read on the last day, which happened to fall on the last day of 2011 (O.S.). I have long noticed that discussing Nabokov in public often sets even experts somewhat ill at ease, with the result that almost every paper read at conferences contains, and transmits to auditors, larger than standard doses of crafted humor, summoned as if to cover the uneasiness that this uncomfortable genius causes in a contemporary mind. My text, however, was straight-faced humorless. Its subject was, as is stated elsewhere in this book, a staggering chance meeting an improbable alternative to chance. The conference took place in a modern, highly efficient building where, in order to save energy, rooms would go dark after a preset period of inactivity within; flail your arms, and the light might come on. This was the metaphor that at the last minute I had prepared to deploy if asked what I made of my observations, hoping that it would not be taken for a wisecrack. But I read next to last, there was little time for questions, and nobody raised a hand.

The book consists of five parts. The first sets forth the chief psycho-philosophical problem of the function and direction of memory in dreamland; introduces John Dunnes treatise on the subject of serial Time, comparing it with the contemporary, although then largely unpublished, research by Pavel Florensky; and describes Nabokovs dream experiment, which was based on the premise and instructions gleaned in Dunnes book. The second part contains an annotated transcription of Nabokovs dreams (as well as a number of his wifes) in the fall of 1964, published for the first time, collects various fabricated dreams one encounters in Nabokovs books, both Russian and English, grouped under the categories that he defines in his experiment, with the addition of new rubrics as required: Nabokovs characters appear to have a broader range of dream variety than did their maker. The last part defines and enlarges on the subject of Nabokovs view of time as a primary structuring condition of existence and specifically of the intricate cooperation of memory and imagination in life and in fiction writing, with often an unpredictable outcome: precognitive verging on prophetic.

, without which the book would have been so much leaner in substance and plot.

Forty years ago Nabokov registered his gratitude to Princeton University Press that, upon acquiring the Bollingen Series, brought out a much revised edition of his monumental translation and interpretation of Eugene Onegin. I, too, am indebted to the generosity of that excellent press for consenting to publish this slim book and to Miss Anne Savarese, executive editor of literature, for her unfailing enthusiasm, a large number of suggested improvements, and proficient management of the entire multitiered process that has made this book a material reality. I am thankful to Dr. Daniel Simon for his lint-roller thorough copyediting of my text; to Mr. Christopher Ferrante, whose artistic taste and skill turned it into a handsome thing; to Dr. Kathleen Cioffi, Senior Production Editor, for her imperturbable attention to smallest details and textual crotchets; and to my daughter Maria Sapp, who caught a number of important flaws at page-proof stage.

I want to make special and uncommon mention of the reader whom the press engaged to review this book for them and who went far beyond the usual reference duty and combed my text with utmost attention, so that

no levelld malice

Infects one comma in the course I hold.

I owe this anonymous colleague more than I can express.

Gennady Barabtarlo

A small selection appeared, with my introduction and brief commentaries, in the Tmes Literary Supplement (October 31, 2014).

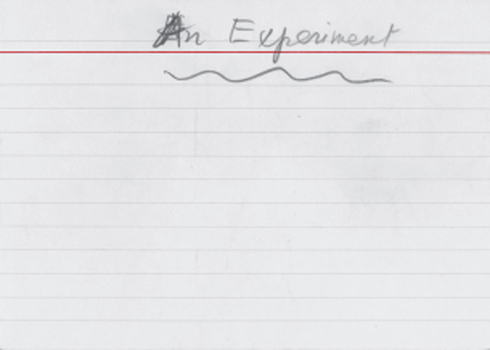

INSOMNIAC DREAMS

The title card for the dream-recording experiment Nabokov began in October 1964.

Tme is... but this book is about that.

J. W. Dunne, An Experiment with Tme

ON OCTOBER 14, 1964, in a grand Swiss hotel in Montreux where he had been living for three years, Vladimir Nabokov started a private experiment that lasted till January 3 of the following year, just before his wifes birthday (he had engaged her to join him in the experiment and they compared notes). Every morning, immediately upon awakening, he would write down what he could rescue of his dreams. During the following day or two he was on the lookout for anything that seemed to do with the recorded dream. One hundred and eighteen handwritten Oxford cards, now held in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library, bear sixty-four such records, many with relevant daytime episodes.

The point of that experiment was to test a theory according to which dreams can be precognitive as well as related to the past. That theory is based on the premise that images and situations in our dreams are not merely kaleidoscoping shards, jumbled, and mislabeled fragments of past impressions, but may also be a proleptic view of an event to comewhich offers, as a pleasant side bonus, a satisfactory explanation of the well-known