Vladimir Nabokov

THE TRAGEDY OF MISTER MORN

With an Introduction by Thomas Karshan

Translated by Anastasia Tolstoy and Thomas Karshan

Contents

THE TRAGEDY OF MISTER MORN

Introduction

The Tragedy of Mister Morn was Vladimir Nabokovs first major work, and the laboratory in which he discovered and tested many of the themes he would subsequently develop in the next fifty-odd years: the elusiveness of happiness; the creative and destructive playfulness of the imagination; courage, cowardice, and loyalty; the truth of masks; the struggle of freedom and order for possession of the soul; the sovereignty of desire and illicit passion; and what one character calls that likeness which exists/between truth and high fantasy (), a likeness under whose inspiration Nabokov would take reality, fancy, art, and impossibility, and twist them together into the four-dimensional knots of Lolita, Pale Fire, and his other great novels.

Yet Morn, which Nabokov wrote in Prague in the winter of 1923 to 1924, when he was only twenty-four years old, was never performed or published in his lifetime, though several readings of the play did take place in Berlin, then Nabokovs home, in the spring of 1923. The opportunities in Berlin for staging a Russian play by a nearly unknown writer were limited, and publication cannot have seemed financially attractive to the migr publishing houses that would later print Nabokovs novels. In America, and then in Switzerland, Nabokov translated most of his Russian fiction, but not his early plays, and when he died, in 1977, the typescript and fair copy of Morn still lay dormant in his personal archive in Montreux. Then, in 1997, Zvezda, a Russian literary journal, published the complete Russian text of Morn; and in 2008 the play finally became available to a wider (Russian-reading) audience when a revised version of the text was published in book form by Azbuka Press of St. Petersburg. These publications have in turn made possible this current editionthe first translation of Morn into English.

While Morn is in many respects the seedbed for Nabokovs major novels, there are also elements in it which are fascinatingly unlike anything in his later work, and which reflect issues in Nabokovs life at the time of writing. Most prominent of these is revolution. Nabokov came from a distinguished liberal family in St. Petersburg: his father, V. D. Nabokov, had been one of the ministers in the short-lived Kerensky government which ruled between the fall of the Tsar and the ascent to power of Lenin and the Bolsheviks in 1917. That year, the Nabokov family fled St. Petersburg, first for Yalta, then for London, and, eventually, Berlinwhere the young Nabokov would rejoin them in 1922, after completing his degree at Cambridge. Even in Berlin, however, the Nabokov family was not safe from the extremist ideologies of right and left which had vied for power in Russia after the failure of the liberal centre, and on March 28, 1922, Nabokovs father was shot dead by a Monarchist assassin who was in fact aiming not at him but at another migr politician.

Nabokovs hatred of the Soviet regime is directly expressed in much of his writing, most prominently his novels Invitation to a Beheading (193536) and Bend Sinister (1947). But he would never again write anywhere nearly so directly about the moment of revolution itself, or so probingly about ideology, as he did in Morn. In the plays two main revolutionaries, Tremens and Klian, Nabokov depicts a politics and poetics of nihilism which, it is implied, was the driving force behind the Russian Revolution. In this Nabokov was refining a critique of revolutionary ideology which can be traced back as far as Turgenevs Fathers and Sons (1862) and Dostoevskys The Possessed (1872). He would articulate this critique again in his last, and greatest, Russian novel, The Gift (193738), whose fourth chapter is a mocking biography of Nikolai Chernyshevskythe revolutionary thinker of the 1860s who was the object of Turgenevs and Dostoevskys conservative critiques, and would become Lenins hero. But in Morn Nabokov explores more fully and explicitly than he ever would again what he saw as the origins of the revolutionary impulse in a death-instinct and passion for destruction. When Ganus, who had once been a revolutionary, returns from exile and discovers the happiness that the masked King has brought to the kingdom, he asks Tremens why he is not now satisfied. Tremens pours scorn on him. Neither happiness nor equality is Tremenss purpose, he explains; rather, he is seeking to imitate the violent destructiveness of life itself, which rushes headlong/into ash, [and] destroys everything in its way (). To him, this destruction is beauty:

Did you see,

one windy night, by moonlight, the shadows

of ruins? That is the ultimate beauty

and towards it I lead the world.

()

Tremens cites as one aspect of that destructiveness the sexual drive itself, in the figure of the maiden, who prays for the blow of a mans love (I.i.294), and one distinctive quality of the play is an unblushing erotic candour to which Nabokov would not fully return until Lolita (1955). Thus Klian, the violent-minded revolutionary poet who serves as Tremenss factotum, tells his fiance Ella that

To enter you, oh, to enter,

would be like entering a tight and searing

sheath, to gaze into your blood, to break

through your bones, to learn, to grasp, to touch,

to press your being in between my palms!

()

This anticipates Humbert Humbert in Chapter 2, Part Two of Lolita saying that my only grudge against nature was that I could not turn my Lolita inside out and apply voracious lips to her young matrix, her unknown heart, her nacreous liver, the sea-grapes of her lungs, her comely twin kidneys. Yet, as with so many aspects of the play, in the sphere of desire Nabokov explores opposite poles of experience. Against Klians dark vision of sexual appetite is set a more salubrious expression of loves idealizing powerin the faith that Midia, and the other citizens, place in Morns nearly magical beneficence, and in Ellas idea of love as a force that coalesces experience:

all is one: my love and the raw sun,

your pale face and the bright trickling icicles

beneath the roof, the amber spot upon

the porous sugary snow mound, the raw sun

and my love, my love

()

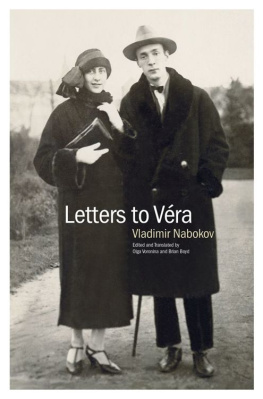

This, and the tenderly specific attention paid to the minutiae of Ellas hair, clothes, and make-up, seem to attest to the fact that Nabokov wrote Morn soon after meeting and falling in love with Vra Slonim, who would become his wifeand the plays typist. With her girlishness, humour, and idealism, Ella ranks alongside Lolita as one of Nabokovs few fully realized female characters.

If, in its treatment of revolutionary ideology, death, and desire, Morn shows us elements that Nabokov would not develop again, or not for a long time, there is one respect in which it stands very obviously as the source of Nabokovs immediately subsequent writing, and this is in its exploration of the twin themes of happiness and make-believe. In 1924, Nabokov would begin writing his first novel, Happiness