Copyright 2017 by Stephan Talty

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-544-63338-4

Cover design by Brian Moore

Cover photograph J. S. Johnston/Getty Images

e ISBN 978-0-544-63535-7

v1.0317

To the memory of my father,

the immigrant

Non so come si pu vivere in questo fuoco!

(I dont know how its possible to live in this fire!)

AN ITALIAN IMMIGRANT ON FIRST SEEING NEW YORK CITY

Prologue:

A Great and Consuming Terror

On the afternoon of September 21, 1906, a high-spirited boy named Willie Labarbera was playing in front of his familys fruit store, two blocks from the glint of the East River in New York City. Five-year-old Willie and his friends ran after one another shouting at the top of their lungs as they trundled hoops down the sidewalk, laughing when the wooden rings finally toppled onto the cobblestone street. They ducked behind the bankers and laborers and young women wearing ostrich feather hats, making their way home or to one of the neighborhoods Italian restaurants. With each wave of pedestrians, Willie and the other children would vanish from one anothers sight for a second or two, then snap back into view once the walkers passed by. This happened dozens of times that afternoon.

More people passed, hundreds of them. Then, as the silvery river light began to dim, Willie turned and dashed down the street once more, disappearing behind yet another group of workmen. But this time, after the pedestrians had strolled past, he failed to reappear. The spot on the pavement where he should have stood was empty in the fading sunlight.

His friends didnt notice right away. Only when they felt the first pangs of hunger did they slowly turn and examine the small expanse of sidewalk where theyd spent their afternoon. Then they began to look for Willie more earnestly in the lengthening shadows. Nothing.

Willie was headstrong and once boasted that hed run away from his parents as a lark, so perhaps the other boys hesitated a few moments before entering the store and reporting that something was wrong. But eventually they had to let the adults know, and so they went inside. After a few seconds, the boys parents, William and Caterina, dashed from the shop and began searching the surrounding streets for some sign of the child, calling out to ask the proprietors of candy stands and small grocery stores if theyd seen the boy. They hadnt. Willie was gone.

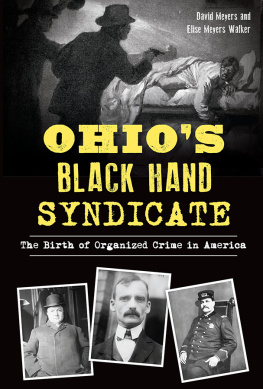

It was at this moment that something odd and almost telepathic occurred. Even before the police had been called or a single clue was gathered, Willies family and friends simultaneously arrived at a revelation about what had happened to the boy, without speaking a single word to one another. And strangely enough, people in Chicago or St. Louis or New Orleans or Pittsburgh or the tiny unheralded towns strung between them, the mothers and fathers of missing children, of whom there were more than usual in the fall of 1906, would have come to the same conclusion. Who had their child? La Mano Nera, as the Italians called it. The Society of the Black Hand.

The Black Hand was an infamous crime organizationthat fiendish, devilish and sinister bandthat engaged in extortion, assassination, child kidnapping, and bombings on a grand scale. It had become nationally famous two years before with a letter dropped into a mailbox in an obscure neighborhood in Brooklyn, at the home of a contractor whod struck it rich in America. Since then, the Societys threatening notes, adorned with drawings of coffins and crosses and daggers, had appeared in every part of the city, followed by a series of gruesome acts that created, according to one observer, a record of crime here during the last ten years that is unparalleled in the history of a civilized country in time of peace. Only the Ku Klux Klan would surpass the Black Hand for the production of mass terror in the early part of the century. From the bottom of their hearts, one reporter said of Italian immigrants, they do fear them with a great and consuming terror. The same could have been said for many Americans in the fall of 1906.

When the letters began arriving for the Labarberas several days later, their fears proved correct. The kidnappers demanded $5,000 for Willies return, an astronomical sum to the family. The exact words the criminals used havent been passed down, but such letters often contained phrases like Your son is among us and Do not give this letter to the police for if you do, by the Madonna, your child will be killed. The message was reinforced by drawings at the bottom of the page: three crude black crosses had been inked onto the paper, along with a skull and crossbones. These were the marks of the Black Hand.

Some claimed that the group and others like it not only were creating an entirely new level of murder and extortion in America, a dark age of spectacular violence, but also were at that moment acting as a fifth column, corrupting the government to their aims. This idea had plagued the new immigrants from Italy for at least a decade. There was a popular belief, said Massachusetts senator Henry Cabot Lodge about a supposed Italian secret society, that it was extending its operations, that it was controlling juries by terror, and that it would gradually bring the government of the city and State under its control. Skeptics, including the Italian ambassador, who bristled at the mere mention of the Society, countered that the group didnt exist, that it was a myth created by Americans to curse Italians, whom the whites hated and wished to drive from their shores. One Italian wit said about the Society, Its sole existence is, in fact, confined to a literary phrase.

But if the Society was a fiction, then who had Willie?

The Labarberas reported the kidnapping to the police, and soon a detective knocked on their door at 837 Second Avenue. Joseph Petrosino was the head of the famous Italian Squad, a short, stout, barrel-chested man, built like a stevedore. His eyeswhich some described as dark gray, others as coal-blackwere cool and appraising. He had broad shoulders and muscles like steel cords. But he wasnt a brute; in fact, far from it. He was fond of discussing aesthetics, loved opera, especially the Italian composers, and played the violin well. Joe Petrosino, said the New York Sun, could make a fiddle talk. But his true vocation was solving crimes. Petrosino was the greatest Italian detective in the world, declared the New York Times, the Italian Sherlock Holmes, according to popular legend back in the old country. At forty-six, hed already had a career as thrilling as any Javert in the mazes of the Paris underworld or of an inspector in Scotland Yarda life as full of adventure and achievement as ever thrilled the imagination of Conan Doyle. He was shy with strangers, incorruptible, quiet-voiced, brave to an almost reckless degree, violent if provoked, and was so adept with disguises that his own friends often passed him by on the street when he was wearing one. He had only a sixth-grade education but possessed a photographic memory and could instantly recall the information printed on a piece of paper hed glanced at years before. He had no wife or children; hed dedicated his life to ridding America of the Society of the Black Hand, which he felt threatened the republic he loved. He hummed operettas as he walked.

Petrosino was dressed in his customary black suit, black shoes, and black derby hat when William Labarbera opened the door of his apartment and escorted him in. The father of the missing boy brought out the letters hed received but could tell the detective little else about the case. The Black Hand was everywhere and nowhere; it was almost occult in its all-knowingness, and it was cruel. This both men knew. Petrosino could see that Willies parents were nearly crazed with grief.

Next page