Everybody hurts.

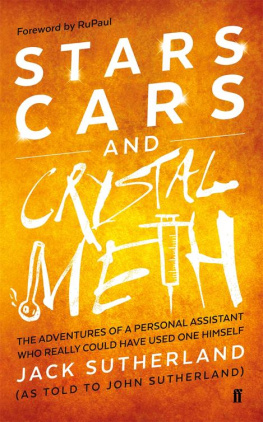

Jack and I came to know each other back in 2000, when he was the chauffeur who drove me to an appearance for Out-fest. We started to casually chat on the trip back home, and we took to each other from that first meeting, on that hot day in Hollywood. My sense that Jack was someone special was confirmed as I saw him, a day or two later, attempting to do a lap round my pool in orange Speedos and high heels. This, I thought, is a man who does not take himself too seriously. The twenty-two marbles what a surprise. Who would have known!

Over the years we remained close friends and I saw him go up and down. His downs were quite extreme and intense its a wonder he ever came back, but fortunately he did and he has. That was very clear to me on our last meeting in London in 2015.

This is a brave book, I think, and one which Jack has put on paper (Jack an author who would have thought it?). He has decided to open up his eventful and colourful life for all to read for one reason only, as he says: to help others who are struggling to cope with life and addiction.

Love, Ru

You, the man said, weighing his words thoughtfully, are the biggest fuck-up I have ever known in the whole of my life.

He didnt say it unkindly. But he didnt say it nicely, either. There was no reason he should.

From him, a compliment of a kind. Mickey Rourke had himself, as he often admitted, been washed up more often than the proverbial greasy-spoon breakfast plate. He knew the ups and downs of life: none better.

Hed twice taken his career into the ring and had his face rearranged, beyond the skill of cosmetic surgery, in regular facial encounters with glove and canvas.

The angelic features which had propelled the young Mickey into world fame with his early cameo in Body Heat (two minutes still studied in every screen-acting school) were gone. A certain menace remained, though. Particularly when it was glowering two inches from your face.

Perhaps he was right. About me. Well, the fact is, he was most certainly right. Hed been good to me, and Id let him down, big time. Fuck-up I was. But then, however often he was counted out, Mickey himself had always come back, hadnt he? Wasnt there hope? Even for fucked-up me?

This was 2010. After his early success, hed sunk low. But his performance in The Wrestler (#1 on ranker.coms list of his movies) and his OTT depiction of gravel-voiced evil in Iron Man 2 had made him Hollywoods comeback kid.

Mickey Rourke was back where he belonged: on top. And, at this moment, looking down from that great height on me. A stain on the red carpet. Wrecked by methamphetamine. (The only way I could do the impossible job demanded of a Rourke PA, I told myself. Not true, but it was all I had to hold on to.)

Long and short? I was fired. And if that was all, I was lucky.

Could I, now the certified biggest fuck-up Mickey Rourke had ever known in the whole of his fucking life, come back? Iron Jack 2? It was 2010. Winter. New Mexico. Snow. And I was in a T-shirt.

Ive just read (November 2014) that hes gone back into the ring, aged sixty-two. In Russia. Putin loves him, apparently.

Hes still on top: Sin City 2.

Its not a good start in life to be Irish and illegitimate. Download the movie Philomena from iTunes and stock up with Kleenex to see why. I escaped being transported, like Irelands lost generation of bastardy, to far-off places, to be abused as forced labour or a sex slave. I escaped the septic tank in which, as I happened to read in a recent Buzzfeed article, Irish nuns simplified the disposal of the unwanted bastard babies theyd starved to death. Thats how those sisters of mercy regarded children who came into the world like I did. Sewage. Ireland has never loved the children of fallen women. Which is how I started life. Fallen-woman spawn.

My birth mother, as best Ive ever been able to find out, was a salesperson in a Dublin shoe store. Young and pretty, I like to fantasise. Theresa Hennessy was the name on the birth certificate a suspiciously common name in Ireland. Once when I was (temporarily) rich and found myself residing in an Irish castle, I toyed with the idea of going on the hunt for Theresa. But I lost my nerve in the face of being rejected again. On another occasion I employed a private investigator to track her down. No luck. Its like looking for a newsagent called Patel in Birmingham, a busboy called Hernandez in San Diego or, come to that, a Jack Sutherland in Scotland. If it was a false name, as I now think, Theresa chose well. Her story will never be told. Perhaps it doesnt need to be. In Ireland its a common enough story.

This much I do know. My birth mother got into trouble (that uniquely Irish euphemism) with a married man, about whom I know nothing. Divorce was not an option even if the bastard (the real bastard in this case) was inclined to do the decent thing and make an honest woman of my BM. Which he clearly wasnt. Ireland didnt approve of breaking the sacred vows of marriage.

The above facts are the sum total of what I got from the friendly English obstetrician who treated Theresa in her last weeks of pregnancy. This was 1973. For five years there had been legal abortion in England. Nothing would have been easier for Theresa than to make a first-trimester long-weekend trip, Dublin to Liverpool. Two hours in the family planning clinic, a cup of tea, soothing conversation and a biscuit, then back, free as a bird, to Ireland, an honest woman again.

Instead Theresa managed to keep her trouble secret and came over to England to give birth, not to abort. She had evidently decided she was not going to kill her baby. Nor was she going to pass him/her to the kindness of nuns and their septic-tank solution. She arranged to pass him/her over by private adoption (legal then, not any more) to a good home the obstetrician helped in England. Having accomplished that, Theresa went home, never to be heard of again at least by me.

My coming into the world was in an anonymous East End London hospital, where perhaps Theresa had discreet friends in the neighbourhood. Or perhaps she just stuck a pin into the map to find somewhere no one would think to look.

My birth mother, brave woman, did not take the easy way. I hope she went on to have a good life. If she reads this book, she can contact me. My message in a bottle.

As I say, I was lucky. And the luck kept running strong. I was adopted, at birth, by a couple who really wanted a baby. Both my parents, hereafter my mother and father, were highly qualified professionals. Egg-headed, as they say. Many notches above sales assistants in shoe shops. Or anything Id ever be.

Both had PhDs my father three of them. Id need a space suit to make a trip to Planet Learning. I dont miss it. I was programmed, genetically, for different things.

I came to consciousness of the world around me in a large South London family house, in a community of similar families whod ended up in Herne Hill (lovely name) because it was the last place in outer London where, in the early 1970s, you could get a half-decent house for under ten grand. It had once been a hill of herons woody lanes and fields with herds of cows to supply inner London with its daily milk. Now it was a yuppie ghetto.

I could now buy that house, at its 1973 price, with my credit card. When I was at my highest earning I could have bought half the street. Holmdene Avenue, it was called. (Sheltered valley, my father once told me. In fact it was a terrace developed in 1910, when the railway opened up the area to jerry-building developers.) I loved the house, which was all nooks, crannies, dark cupboards, coal-holes and long steep staircases. And dry rot, it was later discovered. That somehow figured. It seemed, to little me, as big as a palace, and mysterious as Oz. I took a look at it the other day (now I live down Half Moon Lane in nowadays des-res Brixton). Its just another blah terraced house. No magic. And they cost a cool million too. No yuppie need apply. Bugger off to Scratch End.