Julian Evans - Transit of Venus

Here you can read online Julian Evans - Transit of Venus full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1992, publisher: Pantheon, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Transit of Venus

- Author:

- Publisher:Pantheon

- Genre:

- Year:1992

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Transit of Venus: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Transit of Venus" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Transit of Venus — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Transit of Venus" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For my mother and father

All things of the sea belong to Venus; pearls and shells and alchemists gold and kelp and the riggish smell of neap tides, the inshore green, and purple further out and the joy of distances and the roar of falling masonry, all these are hers, but she doesnt come out of the sea for all of us

John Cheever

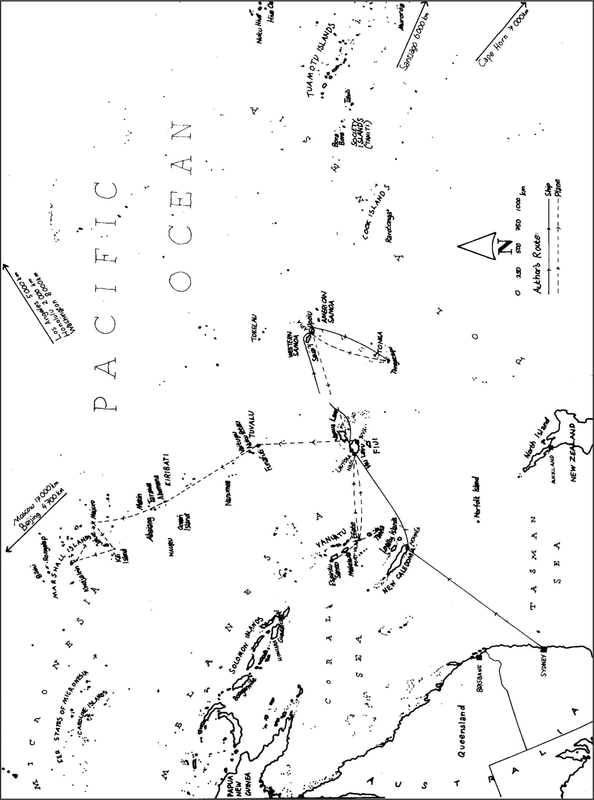

T RANSIT OF V ENUS is about a journey to the islands of the Pacific to discover what happened to their captivating inhabitants of old.

Julian Evanss travels lasted five months. He had read all the old accounts of the great navigators who first saw them, including that of Captain Bligh of the Bounty who wrote: I left these happy islanders with much distress, for the utmost affection, regard and good fellowship was among us during our stay. We know that the mutiny that overtook him was through the desertion of his sailors, who asked no more than to be allowed to spend the rest of their lives in Tahiti.

Evans clearly nourished hopes that something of this island grace and charm might have survived in some remote corner of this vast archipelago. It was a rose-coloured misconception that fades rapidly when his travels begin. He takes advice in his search for an uncorrupted corner of Eden and is directed to Tarawa, a remote atoll in the Gilbert Islands, described by a contact who has sailed the Pacific for fifteen years as the most primitive place he has ever seen. Nevertheless, Tarawa possesses an hotel in which the author is lodged in an insanitary room, and on returning to it without warning surprises the chambermaid watching a porn video. Tarawa also has a Paradise Club where he is entertained by fourteen-year-old dancers. Any one you want, you say, his host tells him invitingly.

The terrible fate that has overtaken the Pacific since the days of Cook reaches its conclusion in the Marshall Islands, scene of sixty-four atomic tests, in which the islands of Bikini and Enewetak were vaporised after the distribution of their reluctant inhabitants around neighbouring islands.

Evans manages to wangle a visit to Kwajalein used by the US Army as a transcontinental firing range on which US personnel are accommodated in 250 stainless steel trailers. There is virtually nothing to do, and after a few days of this he finds himself joining the rest to watch the video commercials in the supermarket. People fight boredom by eating enormously, and for size, he says, would have trampled a Sumo wrestler underfoot.

No Marshallese live on Kwajalein, but segregated local labour is housed on a dormitory islet transformed into a terrific slum. In this, the majestic Polynesian women of the past have become what the Americans call mud-hens. They are totally promiscuous and share with Marshallese in general the highest syphilitic rate in the world. Evans notes that children feeding solely on Coke and ice-cream come close to starvation.

Returning to Kwajalein, it strikes him for the first time that there are no coconuts in the palms. Nothing could have been more symbolic, he thinks, but the fact is that the nuts are removed in infancy. Can you imagine what it would be like if one of those mothers fell on your head? his US minder explains. Despite the authors inability to draw comfort from any aspect of his travels, this is far and away the best book about the Pacific of our times.

Norman Lewis

S OMEWHERE IN S YDNEY , a water-city with a gothic heart and an unquenchable thirst, there is a fat man with a sunburnt face called Norman.

He was in his mid-seventies, at a guess. He was wearing a pale grey suit and a boater with a purple hydrangea in the hatband. A transparent polo shirt stretched over his stomach like pork muslin; his rough, mottled face gave him the look of an old stockman who had spent his life under the sun. His hands were raw at the knuckles: the left clenched the knob of a blackwood cane which he tapped at with the palm of the other, revealing the impatience beneath his courtesy.

But the most striking thing about him was his eyes. They were a hazy grey-blue, like the colour of far hills, unnaturally bright. The rest of his appearance made him faintly comical. His eyes had a suggestion of lunacy.

The pubs in Sydney are not places to strike up casual friendships. Full of raw-faced men in tiny shorts, they have an air of fuddled calculation. If Australia were still a prison colony, these drinkers would be working out how many days and years they had left. As it is, they work out how far they can escape with drink, and take out their discontent on strangers. In a pub by the docks where they had strippers every lunchtime, a wharfie leaned over and hissed in my ear: Er you a fuckin pom? Yer all fucking pisspoor, except for Missis Thatcher. An hour later, at a hotel in the business district, a blond man with the soused features of a fallen angel said: Dontyer hate fucking wogs? He stuck his chin out and wheedled for the answer he wanted. His cousins in South Africa wrote to him regularly, extolling the virtues of apartheid. To underline that his oratorical powers were undiminished by alcohol, he added, Oyve drank twenny-five Heinekens, but his coordination was so poor that as he said it he was pouring the twenty-sixth over his shoes.

I thought I would be safe in the Occidental Hotel, a sedate place of echoing bathrooms and recent immigrants. I ordered a brandy and soda. When it came, a Sydneyite down the bar with delicate red ears stood up unsteadily.

Our beer not good enough for you?

I shrugged and said yes and waited for the fight to develop, deciding I would only have one chance to hit him before the whole bar was on me. I was aggrieved enough to hit him, and persecuted enough to think the bar would take his side. But suddenly he thought better of whatever he had had in mind. Fucking snob, he said it was a change from fucking poms and fucking wogs, at least Ive had enough. Then he staggered through the double doors, still holding his beer glass, and I heard the glass smash in the street outside.

Norman had witnessed the third encounter. I saw the boater and the hydrangea and the steady, bright stare and thought: Another madman. But he bought me a brandy and soda and said, You dont want to take any notice of that. Its only your accent. He fished a card from the breast pocket of his jacket. Anything I can do. You only have to let me know.

The card said, Norman Garvey, Hon. Order MBE, Chairman, City Construction Ltd, and gave his office and home phone numbers. There was no address.

Norman fixed his pale gaze on me. What are you doing in Sydney?

For ten days, I said, I had been trying without success to get a passage on a ship to the western Pacific. The answer was always the same. At one shipping office the clerk in charge of schedules looked up and said bitterly, Ive worked here for fifteen years, and if I cant get a passage you certainly cant. At Darling Harbour a Yorkshireman just in from Auckland, drinking cheap Scotch with a woman whose powdered bust jostled at her neckline like puppies in a sack, gestured around the narrow, dark officers mess: Its all cargo, cargo, cargo now.

Norman hoisted himself onto a stool and began to complain about his rheumatism.

If he had been younger he would have taken me there himself. I went to sea at thirteen, had my masters ticket at twenty and a half. He was staring over my shoulder. I turned round. A blonde girl in a white teeshirt stared defiantly back. The hydrangea wobbled as Norman raised his boater to her and said, Youre a very beautiful young woman.

To me he said, You should give it another try. Go back and ask for the bloke who signs on the crews. And remember, anything I can do.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Transit of Venus»

Look at similar books to Transit of Venus. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Transit of Venus and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.