NOTES FROM

THE CVENNES

In memory of my parents, who granted me a love of two countries

ALSO BY ADAM THORPE

FICTION

Ulverton

Still

Pieces of Light

Shifts

Nineteen Twenty-One

No Telling

The Rules of Perspective

Is This The Way You Said?

Between Each Breath

The Standing Pool

Hodd

Flight

Missing Fay

POETRY

Mornings in the Baltic

Meeting Montaigne

From the Neanderthal

Nine Lessons from the Dark

Birds with a Broken Wing

Voluntary

TRANSLATION

Madame Bovary

Thrse Raquin

NON-FICTION

On Silbury Hill

CONTENTS

The urge to know was with me, and the ache. The smell of the soil, the gleam of the wet roads, the faded paint of shutters masking windows through which I should never look, the grey faces of houses whose doors I should never enter, were to me an ever-lasting reproach, a reminder of distance, of nationality... I should never be a Frenchman, never be one of them.

Daphne du Maurier, The Scapegoat (1959)

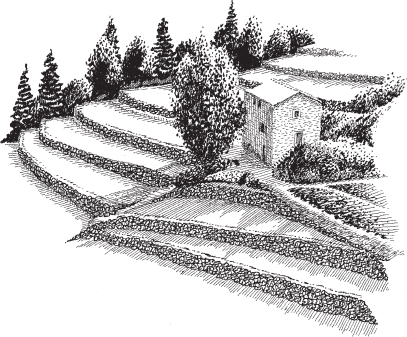

We had been renting full-time in France for three years when we bought our house on the lower slopes of the Cvennes mountains: the last thrust of the Massif Central before the southern plain and the sea. An authors limited budget (one of the reasons for moving to France in the first place) meant that our reverie of an isolated mas or farmhouse with land around it soon dwindled to a rambling village house set against a hill, with a modest, unattached garden behind, sloping up in a series of terraces. At least the kids can walk to school, we told ourselves. Their route was a few minutes down a couple of rocky paths between drystone walls: we had read somewhere, in an article on human evolution, that unevenness underfoot stimulates the synapses, and with the lower path being particularly bouldery, we joked that this would turn them into geniuses.

Your great-grandmother, I told them, walked four miles a day to and from school in cold and rainy Derbyshire. This was warm and relatively dry Languedoc. When it stormed, however, water from the sloping vineyard gushed furiously through a wall on the last stretch, adding to the challenge. Twenty-five years on, the way has recently been paved with shallow steps and cemented flat slabs, doing nothing for the neurones.

Our house is above the village proper. A cluster of largely medieval buildings on the side of a great dome-shaped hill thick with wild boars, our quartier feels like a separate hamlet, with its own name, threaded by rough-cobbled, sloping paths calades, from the Occitan calada (Occitan being la langue dOc, giving rise to the regions name, Languedoc). The main calade passes right by our back door on its way up to the hamlets green or placette the beguiling suffix indicating its size, as a cigarette is a little cigare. This was dominated until a few years ago by the ruin of a medieval building, known as lHpital. Not a hospital, but a refuge for the poorest or the insane. The lower village was destroyed in 1703 (exterminated, in the no-nonsense words of the official command) by Louis XIVs dreaded dragoons of the green tunics, long black boots and five-foot sabres during the guerres des religions, as locals call them. Those that did the burning and demolishing were lodged in our sector, which is why it feels, in parts, like a medieval relic. Theres still a warren of passageways where the old common well can be found, the bucket squeaking into a far-down splash.

Up until some 40 or 50 years ago, the wild limestone hill behind would have resembled the stepped tea or rice plantations of India or Vietnam, rising amphitheatrically with cultivated terraces called bancls in Occitan, put to vegetables like onions, potatoes or leeks, planted with rows of vines, mulberries or olive trees (we are at the very limit of the latters zone). The drystone support walls had to be continually repaired or the heavy rains of autumn and spring would eventually sweep the earth to the bottom, leaving only bare rock. Many bancls have now vanished under bushes or secondary forest. You can see the evidence in the old photographs: a corrugation of thin terraces laboured over with mattock and two-pronged fork for all that the poor soil can give, helped by sheep manure carried in shoulder-yoked baskets up innumerable steps. There is a striking absence of mature trees in these vintage glimpses. The Cvennes were stripped of their timber in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to be happily and heavily replanted in the twentieth with government aid.

The original walls are now half-tumbled among garrigue scrub, or lingering in stretches between pines, chestnut and spruce on the granitic part of our commune a couple of kilometres further north. Where the terraces are better preserved, in areas of the region where more springs bubble up in the aridity, back-to-earthers as well as locals have made beautiful gardens of them, green diadems draped on countless steep shelves. An old Berkshire saying, Neer come home wiout stick or stone, has its Cvenol version in an enormous claps a heap of collected stones stretched among the slopes trees 50 yards above us. A bent-backed veteran warned me soon after our arrival that stones are all that grows in our soil. And grow they do.

Dwarf holm oaks, patched with lichen, may thicken gloomily on the hill (I have grown fonder of them, of their plucky disdain of beauty as well as of cold or heat), but all of a sudden, in late April, the grey-green slopes turn psychedelic for a few weeks, splashed with brilliant orchids, wild garlic, flowering gorse, saxifrage, sage-leaved cistus, wild lavender and trailing honeysuckle, thyme, rosemary and countless other species that include my favourite, aphyllanthes, its tufts of pale electric-blue petals on frail grass-like stalks, blooming only in the day, appearing to wither to invisibility at dusk, then reviving in the morning. Their intense colour is fugitive, impossible to capture in a photograph: they come out a dull white. Small blue and yellow butterflies and grander ones like the scarce swallowtail flicker here and there as you step through the bristle of vegetation, breathing in the warm aromas that herald the imminent heat of cicada season.

At the top of our unprepossessing mount, lonely among the great boulders and sleeve-plucking junipers and thistly undergrowth, you can see the far-off Alps on a clear day, small and sharp as a shrews lower teeth; Mont Ventoux fooling you with its snow-white summit of limestone; the great shadowy key-notes of Mont Aigoual and Mont Lozre to the north; the metallic gleam of the Mediterranean to the south. This peak is where I have stood when lacking inspiration, when my imagination feels valley-consigned, chained down, in need of re-urging.

The end house part of a solid old mas was occupied (and still is) by a family of Seventh Day Adventists, with numerous cousins living elsewhere in the area. The old pastor had just died when we arrived: Grgoire was his son. A bachelor in his thirties, he dressed in black trousers and jacket, sporting a pudding-basin haircut and carrying around with him a battered pocket Bible from which he would quote liberally and fervently when he passed us by the back door, sermonising on the Last Days and how Satan and his angels will rule over a desolate earth until burnt to ashes by God. A relative living in the nearest market town, possibly his aunt (it was never quite clear to me) and of an indefinable age, who dyed her loose hair a corresponding jet black and always wore the same long patterned dress, would trundle an old pram around in Stanley Spencer fashion: it held her shopping, mostly. She had an extraordinarily lugubrious way of speaking, almost a chant, a threnody of complaints with no punctuation. Her partner was a vague, beaming, round-faced presence whose own threaded suit, when he wasnt in a soiled vest, was pale brown and a size too large.