Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

This digital edition published in 2016.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Authors Note

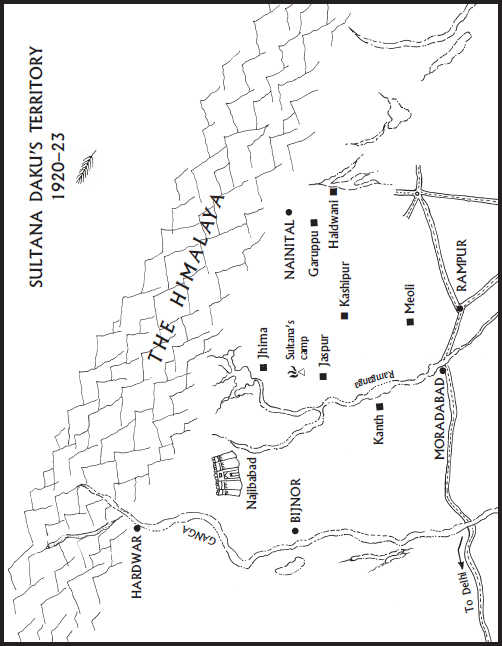

This is a fictional retelling of the legend of Sultana Daku, a bandit who terrorized the United Provinces of British India in the early 1920s.

For literary and historical sources on Sultana Daku and Freddy Young, the author is indebted to Christopher Carnaghan and David Blake of the Indian Police (UK) Association, Professors David Campion, Kathryn Hansen and Devendra Sharma, Pandit Ram Dayal Sharma and the wonderful books of Jim Corbett.

T O HIS DEAR son Rajkumarmay he live longSultan Rajput sends blessings from the government jail in Haldwani on this sixth day of the dark half of the month of Aashaad. The rains have not yet come to Rohilkhand. It is a warm night; the cool morning that follows will be my lastthe hanging has been fixed for sunrise.

A kind English sahib from the army has agreed to write this letter as I speak. Salaam him respectfully when he brings it to you, and do not press him to read it aloud. Find a man you trustone who is allowed to leave the fort with a day passand go to Najibabad with him. There you will find a munshi who reads English. If the munshi insists on being paid, place your knife at his throat.

I will have passed into the lap of Sri Maharaj when you meet the sahib with the letter. Twenty years from now, it will be your turn to be hanged by the government. Until then, know that your father stole as long as he breathed, robbed when he could not steal and killed whenever necessary. Ask the youngest child in Najibabad, the richest shopkeeper in Bijnor, the most powerful landlord in Bareillythey will tell you that Sultana the bhantu was the greatest daku of all.

In two years you will reach the age of six, when a boy must begin to learn the trade of his fathers. Now, listen carefully to the munshi as he reads this, and ask him to repeat the words so you do not forget. There are three hollow spaces inside the mouth where a man may hide coins, rings and small knives: one on either side, between the cheek and upper lip, and a third, secret one, deep inside the throat. There exists a fourth hiding place, not in the mouth but at the other end; keep nothing but silver trinkets there, because gold may not be worn below the waist, let alone kept in a dirty place.

At the age of seven, you must learn how to slide coins from your palm into the sleeve of your kurta, how to hold a long musket against your body so no one suspects you have one, how to speak to a sub-inspector so he thinks you have just woken from sleep, how to excite the pity of an English superintendent of police who is about to arrest you (he will arrest you anyway, but his inspectors will not kick you if he expresses concern), how to engage a shopkeeper in conversation while you steal his grain, and how to pass as a bania though you are dark and thin.

At seven and a half you must learn the language of the jungle, because a bhantu, even one born in jail, is a child of the Bhabar. If you can shriek like a peacock, whistle like a shama bird and chirp like a bulbul, you will never be without words. When the police are about, use these signals to speak to other bhantus: bark like a kakar that has been attacked by a leopard, chatter like a monkey warning the jungle of a tigers approach or make the sound of a porcupine rattling its quills while running from a wild dog.

Before you turn eight and your limbs lose their tenderness, you must learn to squeeze through holes in wallsa diligent boy can pass through a passage that will scratch the sides of a snake. A bhantu does not fear the dark; he does not dread being smothered or suffocated in small spaces. Like a baby in a womb, he stays inside as long as he likes and pushes himself out when the police have left.

A boy of eight must be able to complete at least one roomalinaqab: dig a hole under a locked door and crawl through it. There are two other ways of entering a house: khan-naqab, in which you need to dig through the wall, and bagli-naqab, in which you make a hole in the wall near the door and open the latch from the inside. I do not favour these: you never know who is asleep on the other side of a wall, and people in Bareilly and Moradabad lock their doors from inside. Roomali-naqab is the safest and most effective method: no one sleeps behind a door, and you can always dig a passage under it. If the doorsill is paved, dig deeper and you will reach sand, because nobody lays more than two layers of brick under the door.

Remember not to rob when theft is possible, but do not hesitate to flash a knife if challenged. When necessary, kill. This is the wisdom handed down by our fathers, and that which has been true for four hundred years cannot become wrong in one lifetime.

The best time to poison a man with datura seeds is after he has been outside all day in the hot month of Aashaad, so the police think it is heat stroke. When using arsenic, dye your sheets green in full view of the police, then use some of that dye in the kitchenyour enemy will fall ill. Most banias sell the dye and it is cheap. Remember to burn the dhoti in which you pound and sift the powder, so the police find no trace. When shot by the police or bitten by a snake, look for the brahmabuti plant in the Bhabar jungle. Any bhantu can teach you how to recognize it from its flowers. Tear off three leaves, wash them and squeeze their juice on the wound. It will heal the bite of the most vicious krait and the wound from a police musket, or even an English sahibs rifle.