This book made available by the Internet Archive.

To Rose and Vivica ("Alex"), in lieu of the Citadel

Foreword to the Second Edition

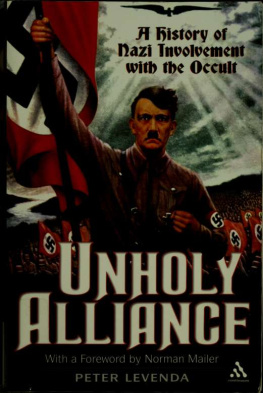

Unholy Alliance is a stimulating book to read for anyone interested in Nazism, magic, the penetralia of history, the cults of the occult, and the present agonizing anxiety of our lives. It is as if something larger than our educations, our sense of good and evil, our lives themselves, seems to be constricting our existence, and this anxiety illumines Unholy Alliance like a night-light in some recess of the wall down a very long corridor.

If magic is composed of a good many of those out-of-category forces that press against established religions, so magic can also be seen, in relation to technology at least, as the dark side of the moon. If a ( ator exists in company with an opposite Presence (to be called Satan, for short), there is also the most lively possibility of a variety of major and minor angels, devils and demons, good spirits and evil, working away more or less invisibly in our lives.

For some, it is virtually a comfortable notion that magic is a practice that can exist, can even, to a small degree, be used, be manipulated (if often with real danger for the practitioner). For such men and women, the proposition is assuredmagic most certainly does exist as a feasi ble processeven if the affirmative is obliged to appear in determinedly small letters when posed against technology: (How often can a curse be as effective as a bomb?)

Nonetheless, given the many centuries of anecdotal and much-skewed evidence on the subject, it is still not irrational to assume even if one has never felt its effects oneselfto assume, yes phenomena of a certain kind can be regarded as magical in those particular situations where magic offers the only rational explanation for events that are otherwise inexplicable. Indeed, this is probably the

Foreword to the Second Edition

common view. One explanation for the aggravated awe and misery that inhabited America in the days after the destruction of the Twin Towers was that the event was not only monstrous, but brilliantly effected in the face of all the factors that could have gone wrong for the conspirators. The uneasy and not-to-be-voiced hypothesis that now lived as a possibility in many a mind was that the success of the venture had been fortified by the collateral assistance of magic. Few happenings can be more terrifying to the modern psyche than the suggestion that magic is cooperating with technology. It is equal to saying that machines have a private psychology and large events, therefore, may be subject to Divine or Satanic intervention.

So let us at least assume that magic is often present as a salient element in the very scheme of things. Anyone who is offended by this need read no further. They will not be interested in Unholy Alliance. Its first virtue, after all, is in its assiduous detail, its close description of the events and ideas of the occultists who gathered around the Nazis as practitioners, fellow travelers, and in the case of Himmler and the SS, as dedicated acolytes, fortified cultists.

What augments the value of this work is the cold but understanding eye of the author. Since his knowledge of magic and magicians is intimate, one never questions whether he knows what he is writing about. Since he is also considerably disenchanted by the life practices of most of the magic workers, he is never taken in by assumptions of grandiosity or over-sweet New Age sentiments. He knows the fundamental flaw found in many occultistsit is the vice that brought them to magic in the first placeprecisely their desire to obtain power over others without paying the price. The majority of occultists in these pages appear to be posted on the particular human spectrum that runs from impotence to greed. All too often, they are prone, as a crew, to sectarian war, all-out cheating, gluttony, slovenliness, ill will and betrayal. Exactly. They are, to repeat, at whatever level they find themselves, invariably looking for that gift of the godspower that comes without the virtue of having been earned.

The irony, of course, is that most of them, in consequence, pay large prices in ill health, failure, isolation, addiction, deterioration of their larger possibilities, even personal doom. Goethe did not conceive of Faust for too little.

Foreword to the Second Edition

Peter Levenda captures this paradox. What he also gives us is a suggestion that cannot be ignored: The occultists on both sides in the Second World War (although most particularly Himmler and the Nazis) did have some real effect on its history, most certainly not enough to have changed the outcome, but enough to have altered motives and details we have been taking for granted. What comes through the pages of Unholy Alliance is the canny political sense Hitler possessed in relation to the separate uses of magic and magicians. Lev-enda's dispassionate treatment of charged evidence is managed (no small feat) in a way to enable us to recognize that Hitler almost certainly believed in magic, and also knew that such belief had to be concealed in the subtext of his speeches and endeavors. Open avowal could be equal to political suicide.

He was hell, therefore, on astrologersand packed ofl many to concentration camps especially after Rudolf Hess' flight to England in 1941, did his best (and was successful) in decimating the gypsy population of Europe, sneered publicly at seers, psychic gurus, fortunetellers, all the small fry of the occult movement. He saw them clearly as impediments to his own fortunes, negative baggage to his reputation. Yet Hitler gave his support to the man he made into the second most important Nazi in existence, Heinrich Himmler, an occultist of no small dimension.

It was as if Hitler lived within a particular Marxist notion. It was Engels' dictum that "Quantity changes quality." One potato is something you eat, a thousand potatoes are to be brought to market, and with a billion potatoes, corner the market. In parallel, a little magic practiced by a small magician can prove a folly or a personal enhancement, a larger involvement brings on the cannibalistic practices to be expected of a magicians' society, and a huge but camouflaged involvement, the Nazi movement itself, with its black-shirted Knight Templars of SS men, becomes an immense vehicle that will do its best to drive the world into a new religion, a new geography, a new mastery of the future.

All of this is in Levenda's book. It is an immense if obligatorily compressed thesisthe economies of publishing would never permit a one-thousand-page tome on this subject by a new authorand the potentially large virtues of the work suffer to a degree from over-compressionone feels the need to expand being held in much too

close rein by the writer, but then, there are few daring and ambitious works that do not generate sizable flaws. Literature may be the most unforgiving of the goddesses!